Today, July 29, 2024, marks the centenary of Elizabeth Short’s birth. Born in Boston, Beth, as she often preferred to be called, was the middle child of Cleo and Phoebe Short. She had four sisters: Virginia, Dorothea, Elnora, and Muriel.

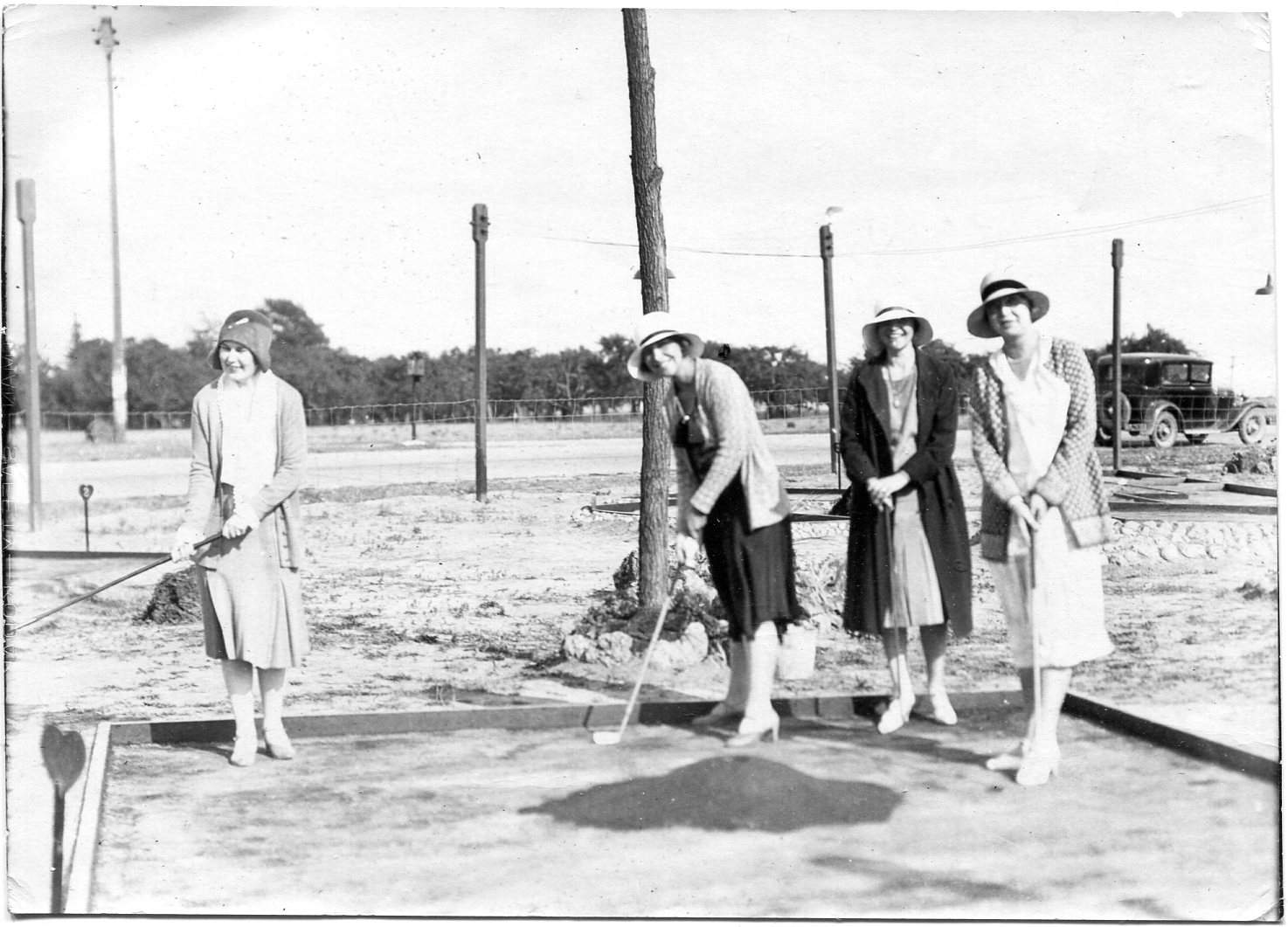

Cleo held various sales jobs over the years. The miniture golf craze of the 1920s captured his imagination. He opened a course, but in 1930, the business tanked. Rather than face the loss, and his responsibilities to his family, he positioned his car close to a bridge to create the appearance of suicide. A houseful of women has its comforts, but Cleo’s abandonment appears to have profoundly affected Beth.

A few years later, Cleo wrote to Phoebe and asked for forgiveness. She refused. At least Beth knew Cleo was alive. She hoped for a relationship. She found him in California. Rather than a loving father, he was a mean drunk, looking for a housekeeper, not a daughter. Their reunion failed.

In 1943, she worked at Camp Cooke, now Vandenberg Air Force Base, where they voted her “Camp Cutie. On September 23, 1943, she got arrested for underage drinking at the El Paseo restaurant in Santa Barbara. The jail matron gave her money for a bus ticket back to Medford, Massachusetts.

Because of her asthma, Beth would regularly escape the harsh Massachusetts winters to work as a waitress in Florida.

Major Matt Gordon, a decorated fighter pilot, met Beth in Miami, Florida while on leave in 1944. He may have been on leave after sustaining injuries in a plane crash in February. A photo of them together shows him smiling, and Beth with stars in her eyes, and a proprietary hand on his arm. The handsome pilot was everything the twenty-year-old wanted.

Matt’s death in a plane crash near Kalaikunda in West Bengal, India, on August 10, 1945, was a cruel twist of fate. It happened just one day after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan, and only weeks before the war ended. Matt’s loss devastated Beth.

After August 1945, she never worked again. She drifted from Medford, to Chicago, Florida, and to Los Angeles—chasing a ghost.

She lived in Long Beach, California, during the summer of 1946. While there, friends nicknamed her the Black Dahlia. By the end of the year, she was couch surfing at the home of Dorothy and Elvera French in San Diego. While in San Diego, she met a traveling salesman, Robert “Red” Manley, when he offered her a ride.

Beth and the married salesman, a fact he no doubt concealed from her, corresponded for a month or two before she asked him if he would drive her back to Los Angeles in early January 1947. He agreed.

Red picked her up at the French’s on January 8th. They drove up the coast and stayed the night in a motel before arriving in Los Angeles on January 9th. Beth checked her luggage at the bus depot. Red refused to leave her in such a sketchy neighborhood. He took her to the Biltmore Hotel, where she told him she was meeting her sister, Virginia. It was a lie. Virginia lived hundreds of miles north in Oakland.

Red stayed with her in the hotel lobby for a long time before he left. Beth, now on her own, left the hotel lobby, turned right on Olive, and vanished.

On the morning of January 15, a Leimert Park housewife, Betty Bersinger, discovered Beth’s body while out running errands. Where was Beth for those missing days? No one who knew her saw her during that time. The thought of her being held captive by her killer is horrifying.

Once police established her identity, reporters saw it as an opportunity to pry into every detail of Beth’s life. The dead lose their right to privacy. Speculation filled column after column in the newspapers. The prevailing attitude was that nice girls do not get murdered. Yet Beth had done nothing, good or bad, worthy of note. At 22-years-old, she never got the chance.

As time passed with no solution, the case grew cold. Other murders captured headlines. It was not until decades later, following a couple of books, and a mid-1970s made-for-TV movie, that Beth’s story became news again.

It is understandable that the case is known in Los Angeles, but what I find most interesting is that the 77-year-old Los Angeles murder mystery has drawn global interest. What is it about Beth’s murder that resonates with people even today?

It may be the supposed Hollywood connection.

Most contemporary articles erroneously describe Beth as an aspiring actress, or starlet. Such characterizations make her murder the ultimate Hollywood heartbreak story with a violent twist.

Still, two distinct narratives about Beth co-exist. One is the myth of the Black Dahlia, a fictional character based on Beth’s life.

The second story, and the one I believe is true, is that of a depressed, confused, and needy young woman seeking marriage and stability in the chaos and uncertainty of the post-war world.

Each of her sisters married and had children. By the time of Phoebe’s death in 1992, three daughters, thirteen grandchildren, twenty-one great-grandchildren, and one great-great-grandson survived her. If Beth had lived, she would undoubtedly contributed heirs.

We have lost sight of the troubled young woman who came to California to connect with her father—not to break into the movies.

The tragedy of Beth’s life is not that she failed to achieve Hollywood stardom, she never sought it.

Beth was looking for what most people her age wanted—marriage and a home. She pursued a romantic vision of a husband in uniform with shiny bright brass buttons, and a bungalow with a white picket fence.

Judging by an undated letter she received from Lieutenant Stephen Wolak, she did not hesitate to press a man for marriage. Wolak’s letter reads in part, “When you mention marriage in your letter, Beth, I get to wondering. Infatuation is sometimes mistaken for true love. I know whereof I speak, because my ardent love soon cools off.”

Wolak’s response to Beth’s letter is a frank assessment of their relationship—which, in his estimation, was not serious. You can gauge her desperation from his response.

How many other men in uniform received letters from Beth suggesting marriage?

A depressed and lonely young woman with daddy issues looking for love is not necessarily the stuff of bestselling books or blockbuster movies.

The pathos of Beth’s real life can make us uncomfortable, so we perpetuate the myth of the Black Dahlia. It is the epic tale of a beautiful young woman seeking stardom who meets a brutal end at the hands of a depraved killer that mesmerizes us.

I imagine in the years to come—no matter what may be revealed; we will continue to hold fast to the myth.