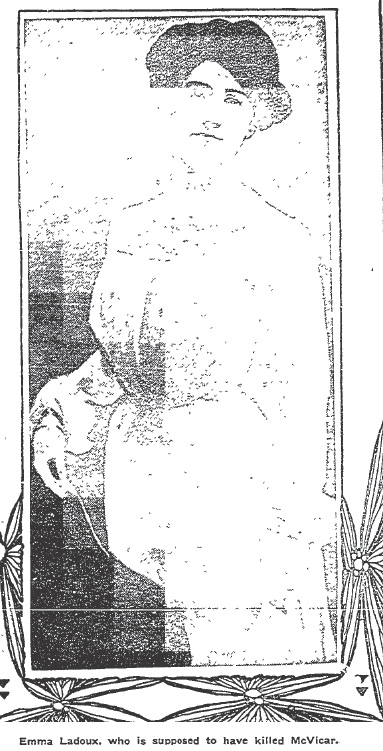

When Aggie Underwood arrived at Tehachapi Women’s Prison in the spring of 1935 she interviewed all kinds of prisoners: murderers, thieves, prostitutes — some of them had been doing time for many years, like Emma Le Doux. Le Doux had started serving her sentence for murdering one of her husbands (Anna was a bigamist) when women were still being sent to San Quentin. Other women, such as Anna De Ritas, had not been in Tehachapi for very long; in fact, Anna hadn’t even been in for a year when she approached Aggie to ask her if there was “something new” happening on the outside.

When Aggie Underwood arrived at Tehachapi Women’s Prison in the spring of 1935 she interviewed all kinds of prisoners: murderers, thieves, prostitutes — some of them had been doing time for many years, like Emma Le Doux. Le Doux had started serving her sentence for murdering one of her husbands (Anna was a bigamist) when women were still being sent to San Quentin. Other women, such as Anna De Ritas, had not been in Tehachapi for very long; in fact, Anna hadn’t even been in for a year when she approached Aggie to ask her if there was “something new” happening on the outside.

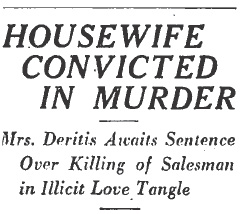

De Ritas was doing time in Tehachapi for the shooting death of her lover, Michelangelo Lotito.

De Ritas had been living with her husband and their four daughters, until she began an affair with wine salesman Michelangelo Lotito. Mr. De Ritas had left Anna in September 1934. Anna’s four young daughters were placed in a Burbank orphanage because Mr. De Ritas couldn’t care for them on his own, and Anna was too wrapped up in her affair with Lotito to give the girls a second thought.

About a month after the De Ritas’ marriage had disintegrated Lotito decided that he’d finished with Anna. One morning while she was out grocery shopping he wrote her a note in which he told her that their affair was ended, with the note he’d left her a check to cover the rent for their apartment at 1650 Echo Park Avenue for the remainder of the month.

Lotito had phoned his brother Frank to come over and help him move his belongings, and he had undoubtedly planned to be gone before Anna returned. Unfortunately he had miscalculated the length of time that Anna would be out — she wasn’t walking home as she usually did, she’d managed to catch a ride with a friend of hers, Lola Martin. Anna appeared just as he and his brother were about to drive away.

Anna would not accept that her affair with the wine salesman was over. She was devastated, and the couple began a protracted shouting match on the sidewalk in front of their apartment building. The distraught woman begged, pleaded, and then her rage began to build. How could he leave her, she wailed, when she’d sacrificed everything to be with him? Could Anna really have been that naive? When her lover refused to reconsider his decision to call it quits she raised the paper bag she was holding. The bag contained a revolver with which Emma shot Lotito through the stomach. Frank saw the muzzle flash through the bag and watched in horror as his brother collapsed to the sidewalk. Frank disarmed her and called the police.

Michelangelo was taken to the Georgia Street Hospital where he was informed he was the 500,000th patient to receive emergency treatment there. Being number 500,000 wasn’t an honor that he would live to enjoy, Lotito died of the gunshot wound several days later.

Michelangelo was taken to the Georgia Street Hospital where he was informed he was the 500,000th patient to receive emergency treatment there. Being number 500,000 wasn’t an honor that he would live to enjoy, Lotito died of the gunshot wound several days later.

Anna testified at her trial that Lotito had persuaded her to leave her husband and daughters, then spurned her. She said that when she confronted him outside of the apartment building they argued, but she denied that she had shot him in cold blood as Frank Lotito had testified. She said that she and Michelangelo had struggled for the gun and it accidently discharged.

Anna testified at her trial that Lotito had persuaded her to leave her husband and daughters, then spurned her. She said that when she confronted him outside of the apartment building they argued, but she denied that she had shot him in cold blood as Frank Lotito had testified. She said that she and Michelangelo had struggled for the gun and it accidently discharged.

The jury found Anna guilty of manslaughter and she was sentenced to from one to ten years in prison.

The L.A Times summed up Anna’s situation in this way: love, death — prison.

![Coroner Frank Nance at his desk. [LAPL photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/coroner_nance_00042037-300x240.jpg)

![Aggie Underwood interviews mourner at funeral of evangelist Aimee Semple Macpherson. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/00034796-240x300.jpg)