This is the third of a series of articles by an International News Service staff correspondent who obtained the first comprehensive inside story of California’s unique all-woman prison.

Tehachapi, Cal., May 2 — Forbidden to read newspapers, their only source of information being occasional letters and visits by friends, the 145 women inmates of California’s “City of Forgotten Women,” Tehachapi, have one question that is always asked early during a visit.

“Something new?” It was the first question asked me by Mrs. Anna de Ritas, 39-year-old convicted slayer of her sweetheart Mike Lotito. The dormitory in which she is housed is by far the “happiest” sounding building of the prison group. Anna de Ritas shot her lover to death.

Housed with her are Miss Thelma Alley, Hollywood actress, convicted of manslaughter in connection with an automobile accident; Mrs. Eleanor Hansen, who murdered the husband whom she charged failed to properly feed her and their daughter; Emma Le Doux, who has spent more than 20 years in state prisons for murder in Stockton.

Another interesting inmate of Tehachapi, and another really happy one, is Mrs. Trinity Nandi who has spent more than 17 years behind prison walls for murder. She is to be released in May, and she is full of plans for the future.

Since her removal from San Quentin to the Tehachapi institution, Mrs. Nandi has been working in the rabbitry and has qualified as an expert. It is her hope to start a rabbit farm when she is released. The women in Tehachapi are learning how to make themselves useful when they leave it.

When Burmah first entered Tehachapi, she was full of ambition and conducted classes in commercial courses, Miss Josephine Jackson, deputy warden, says Burmah did a fine job of it. She taught oral English, typing, and dramatics to fellow inmates.

She fell ill for almost two months and during that illness her ambition and vivacity seemed to disappear.

“I’ve gone into it very thoroughly,” Burmah said softly, and sadly, after announcing that her interviewer was the first visitor she has had since last November. Her father, who was loyal to her throughout her arrest and trial, is dead now.

“The prison board can’t do a thing. The judge who sentenced me fixed that up and I just can’t see any sense in working hard every day when there’s nothing to work for. I can’t see any sense in hoping for the future, when there’ nothing to hope for. I can’t see any sense in training for work to do when I get out of here, because I’ll be an old lady then–maybe not old physically, but I know from what it’s already done to me that I’ll be hundreds of years old mentally.”

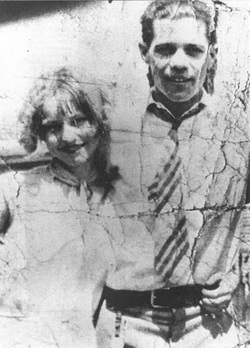

The girl the nation read out as the “jazz baby,” Burmah White, the blonde bandit moll, wife of one of Los Angeles’ most notorious slain criminals, Thomas White, has vanished. The “tough,” cynical 19-year-old girl who entered the prison 16 months ago has been transformed into a quiet mannered, sad-eyed girl, her face framed in soft dark brown hair which she had let grow back to its natural color.

“You know,” she said, with a slightly cynical smile, “they tell me there’s civilization beyond them thar hills!”

“I was an example to the youth of this country when I was sentenced for the wrongs I had done. That was the sole purpose in giving me that stiff sentence–to set an example. I wonder if it has deterred any girls in Los Angeles from a life of crime–I doubt if it even made an impression on any of them,” she said bitterly.

I found she had been making a new blouse out of a bit of silk that she had managed to obtain. A particularly becoming blouse–peach colored, with a white lacing down the front.

“Oh, can you wear those things up here?” I asked her, and then she grinned her old grin and said, “Well, we can wear dark skirts and blouses on Sunday–only the blouses have to be white–but making it helped pass the time of day.”

NOTE: This is the final installment of Aggie’s interviews with inmates in the Women’s Prison in Tehachapi. . When the series appeared, Aggie had been working for William Randolph Hearst for less than a year. The series was syndicated which gave her national exposure, and helped her earn a reputation as a reporter to be reckoned with.

![Aggie Underwood interviews mourner at funeral of evangelist Aimee Semple Macpherson. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/00034796-240x300.jpg)

![Hall of Justice, showing Broadway and Temple St. elevations. Old Hall of Justice showing its south elevation is seen in lower right background, behind county jail. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/hojj_1926_00031871-300x235.jpg)