Incorporated in 1913, San Marino is a quiet, residential-only enclave catering to people with money; lots of money. It is unthinkable, not to mention in poor taste, for a resident to die of unnatural causes. But on December 31, 1949, the body of a 39-year-old socialite, and well-known party girl, Joy McLaughlin, was found in the lush bedroom of her San Marino rental home. A gunshot wound to her chest. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department sent detectives Herman Leaf and Garner Brown to investigate.

When Brown and Leaf arrived at McLaughlin’s Spanish-style bungalow at 2002 Oakdale Street they found the attractive blonde artfully sprawled on a blood-spattered Oriental rug in her bedroom next to her lace canopied bed. If they hadn’t known better, the detectives may have thought that they were looking at a scene from a film noir. The deceased was wearing a maroon off-the-shoulder blouse, blue skirt, and black peep-toed pumps. Her jewelry comprised a simple gold bracelet and gold earrings. A .38 revolver lay near her right hand.

As the detectives scanned the frilly bedroom for clues, they noticed a framed pastel portrait of McLaughlin. The portrait appeared to be from the 1930s. In it, McLaughlin had long blonde hair, kohl-rimmed eyes, and vaguely resembled actress Mary Astor, if she was a blonde. A bullet broke the glass in the portrait. The shattered glass was another film noir touch in the real-life death scene.

What had Joy’s life been like in the years since the completion of the portrait? And why had she died? In order to better understand Joy’s death, detectives would have to examine her past.

According to some records, Joy was born in Denver as Joy McLaughlin on September 22, 1910, or 1911 in Memphis, Texas. By the 1930 census, Joy lived with her widowed mother, Daisy, and her sisters, May, Dorothy, Novella, Ysleta, and Thelma, in a home on Larrabee Street in Hollywood. Joy was 19 at the time of the census, and was in a relationship with automobile (Cadillac and LaSalle) and radio (KHJ) magnate Don Lee. The older man, twice divorced, had been seeing Joy since she was sixteen.

Joy believed she and Don would eventually marry, but he met another age-inappropriate woman, twenty-four-year-old Geraldine May Jeffers Timmons, and dropped Joy like a burning coal. Don and Geraldine dated for only a few months before being married in Agua Caliente, Mexico.

Disappointed and angry, Joy filed a breach of promise lawsuit, aka a “heart balm” suit in 1933 against her former lover in the amount of $500,000. To put it in perspective, $500,000 then is equivalent to $11 million dollars today. Certainly enough cash to soothe a broken heart. Following a brief court battle, Joy walked away with $11,500. Not what she hoped for, but not chump change—it had the same buying power as $266k has today. You could stretch that sum a long way during the Great Depression.

For the next several years, Joy traveled. She sailed through the Panama Canal, she visited Hawaii, and she spent time at the resort in Agua Caliente, Baja California, Mexico. She even found time to marry a man named Robert Stark; but the marriage ended in divorce.

During years before her death, Joy met an oil millionaire, John A. Smith. John was married but when asked about it he said: “I’m not working at it.” During their investigation of Joy’s death, Sheriff’s Department detectives discovered John had been with Joy in the hours prior to her death.

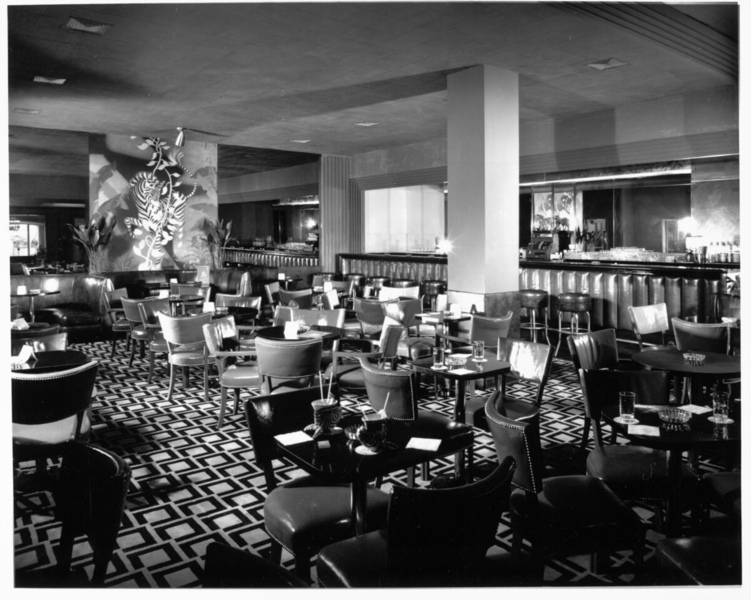

Had John killed her? Not according to his testimony at the coroner’s inquest. John described an evening of drinking (Joy’s blood alcohol registered.021 at her autopsy) and dancing. The couple, accompanied by Fern Graves, a friend of Joy’s, partied at the Jonathan Club and the Zebra Room of the Town House.

John said: “Joy wanted to dance. She called the orchestra leader over and arranged for some music. I bought the orchestra a drink. We danced and drank until the bar closed.” At 2 a.m. Joy, Fern, and John accepted the invitation of bar acquaintance named George to have a nightcap in his room at the Biltmore Hotel. The party continued until 8 a.m. It incensed Joy when John suggested they call it a night. She bolted from George’s hotel room, and John had to retrieve her.

Joy and John finally made it back to her home. Between sobs, John testified Joy became melancholy, and occasionally belligerent, when she drank. He followed her into her bedroom, where she undressed. He said that she turned to him and said, “You can get out.” John said he knew better than to cross her when she was in a mood, so he left the house. As he got to his car, he thought he heard a gunshot. “I ran back into the house. Joy was sitting on the floor…”

John fell apart on the stand, and it took him several moments to regain control and continue his testimony. “She (Joy) was sitting at the foot of the bed, sort of half sprawled and leaning against the bed. I saw the whole scene in an instant. Her hand was out, and a gun was lying not over three feet from her body. I grabbed it.”

“I said, ‘My God, what have you done?’” Joy was beyond answering. John picked up the weapon and it went off. It scared him half to death. Joy remained quiet. When John tried to lift her, he felt blood ooze through his left hand. “I listened for life. In my judgment, she was dead.”

He panicked. He left without calling a doctor because he believed Joy was dead. He then drove through a thick fog to the Wilmington home of two of Joy’s sisters, Thelma, and Ysleta. When they opened the door, they found John wringing his hands and crying.

When Joy’s sister Ysleta was called to testify at the inquest, she revealed it was she who gave Joy the weapon that killed her. Friends described Joy as a person who felt things keenly; sensitive and sympathetic to other people’s problems.

Upon hearing from all the witnesses, the coroner’s jury concluded Joy had discharged the .38 firearm into her chest, just one inch from her breast.

There appeared to be no single event which caused Joy to take her own life. Perhaps her suicide was the culmination of a life of unfulfilled dreams.

NOTES: This is another great story I owe to Mike Fratantoni–historian par excellence. It is also an encore post from 2017.

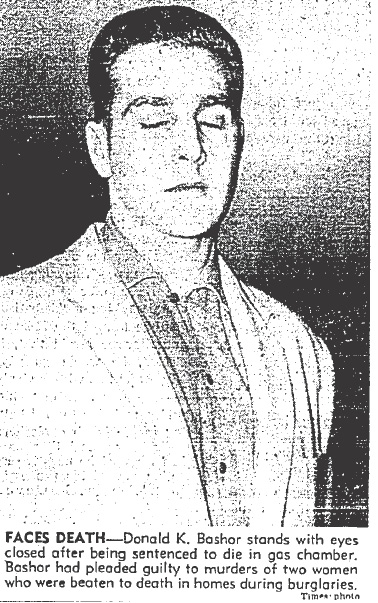

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.

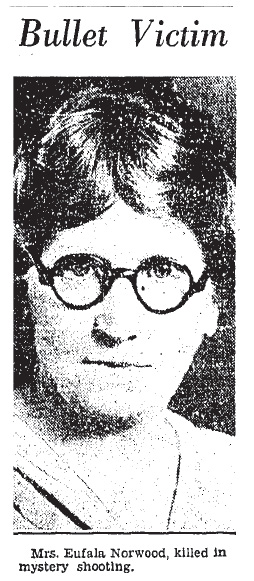

The next day William Norwood, who worked as the registrar as the White Memorial Hospital down the street from his mother’s house, dropped by to see her. When he entered the house he noticed it was extremely quiet. He called out but there was no answer. He went into the kitchen and that where he found his mother. She was dead, but there was nothing to suggest foul play until she was examined at the morgue.

The next day William Norwood, who worked as the registrar as the White Memorial Hospital down the street from his mother’s house, dropped by to see her. When he entered the house he noticed it was extremely quiet. He called out but there was no answer. He went into the kitchen and that where he found his mother. She was dead, but there was nothing to suggest foul play until she was examined at the morgue.

The confession was important, but everyone wanted an explanation. What was the motive? Evidently the two women had had several petty quarrels, and during one of them Eufala ordered Isa to leave the house permanently. Isa found a new place on South Boyle Avenue and on January 18, the day of the murder, she had returned to retrieve the rest of her personal belongings. Moving is hungry work and Isa said that by the time she got to her old digs she needed sustenance. She pulled open the icebox door and found an delicious looking avocado sandwich. She was just about to take a bite when Eufala came in and took umbrage with Isa’s appropriation of her lunch. Eufala made a grab for the disputed treat and Isa became “insanely angry”.

The confession was important, but everyone wanted an explanation. What was the motive? Evidently the two women had had several petty quarrels, and during one of them Eufala ordered Isa to leave the house permanently. Isa found a new place on South Boyle Avenue and on January 18, the day of the murder, she had returned to retrieve the rest of her personal belongings. Moving is hungry work and Isa said that by the time she got to her old digs she needed sustenance. She pulled open the icebox door and found an delicious looking avocado sandwich. She was just about to take a bite when Eufala came in and took umbrage with Isa’s appropriation of her lunch. Eufala made a grab for the disputed treat and Isa became “insanely angry”.