During Prohibition, people drank whatever they could get their hands on—often poor-quality juice. Shady characters distilled booze in basements and warehouses. They cared about nothing but money. Manufacturing overnight whiskey made from “…refuse, burned grain or hay or any old thing that will sour” posed a danger to people’s physical and mental health. After several cocktails containing a noxious blend of chemicals, a person might be capable of anything.

A native New Yorker, Edward P. Nolan came to Los Angeles to make his fortune in the budding film industry. He was luckier than most Hollywood hopefuls. During 1914 and 1915, he appeared in short subjects with Charles Chaplin, Mabel Normand, and Marie Dressler. His most noteworthy appearances were in The Face on the Barroom Floor and Between Showers (1914). He may not have worked in film between 1915, appearing in Hogan’s Wild Oats and 1920, when he appeared opposite Leatrice Joy and James O. Barrows in Down Home.

What Nolan did for a living during the five years between acting gigs is anyone’s guess, but by 1922 he was in the LAPD and had risen to the rank of Detective Lieutenant. Law enforcement was not a reach for him. After all, he played a policeman in several movies.

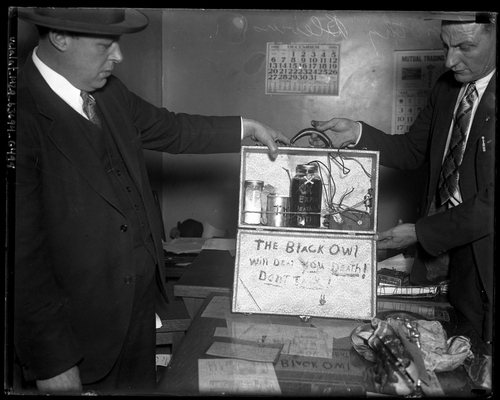

On June 16, 1931, Nolan made a dramatic arrest of an extortionist, George Freese. Freese sent anonymous death threats to A. H. Wittenberg, president of the Mission Hosiery Mills. Pay $700, or die.

Freese instructed Wittenberg to hand the pay-off over to a taxi-cab driver-messenger who would then deliver the cash to him.

When the extortionist phoned with details, Nolan took notes and planned. He prepared a dummy package, and when the cab driver appeared outside the Wittenberg home, Nolan concealed himself in the auto and told the driver to proceed to the rendezvous point. Detective Lieutenants Leslie and McMullen followed in a police car.

Freese waited at the corner of First Street and La Brea Avenue to collect the money. As he accepted the dummy package, Nolan grabbed him.

Freese confessed without hesitation. He held a grudge against Wittenberg because six months earlier, Wittenberg turned him down for a salesman’s job. Freese said he needed the money because his family had fallen on hard times. A common predicament for people during the Great Depression.

The next day, Nolan and his 36-year-old divorced girlfriend, Grace Murphy Duncan, celebrated Nolan’s success in the Wittenberg case at the Hotel Lankershim. The couple spent a lot of time at the hotel while Nolan sought a divorce from his wife, Avasinia. Once the divorce was final, Duncan, and Nolan planned to marry.

At 6:30 pm on the evening of June 17, 1931, Mrs. Helen Burleson, visiting from San Francisco, left her upper floor room, and headed to Nolan’s room on the second floor. She wanted to consult with him on a private matter. When she stepped into the room, she saw Nolan and Grace. Drunk. The lovers quarreled. The shouting reached a crescendo, and Nolan shoved Duncan out of the room. Then threw her coat into the hallway after her.

Grace and Helen went to Helen’s room, where they discussed Nolan’s violent behavior. Grace wanted to inform on him to the LAPD brass, but Helen talked her out of it.

While Grace and Helen talked, a trio of traveling salesmen, Robert V. Williams, Dan Smith, and Jimmy Balfe, went up to Robert’s room to catch a ball game on the radio. Robert said, “After a while, the lights went on in a room across the light well and we saw two women enter the room. Smith said he recognized Mrs. Burleson, and he telephoned to her room and asked her if she wanted to come over and listen to the radio. Mrs. Duncan was with her, and I don’t believe the two were in the room five minutes before Nolan burst in.”

“The ball game had ended, and I had dialed some music. It was about 10:30 o’clock. Mrs. Duncan and I were dancing. Nolan walked right up to her and said, ‘What do you mean by making up to this fellow?’ He pushed her over on the bed. Then he turned to me and said, ‘I saw you kissing her.’ Then he hit me. I staggered back into the bathroom.”

In a drunken rage, Nolan shoved Williams onto the bathroom floor.

Nolan shouted obscenities and waved his service weapon around. Williams stayed in the bathroom and locked the door. The other occupants of the room fled into the hallway, where they watched through the doorway as Nolan beat and kicked Grace. The woman’s screams were loud enough to bring Floyd Riley, a bellboy, up to the 8th floor. He didn’t want to confront Nolan, either. He said, “He looked like a wild man to me. His eyes gleamed, and he cursed incoherently. I could smell liquor on his breath.”

Grace rolled over onto her stomach, but the beating continued. At one point, Smith yelled at Nolan to stop, but was told to, “mind your own business.” Addressing no one in particular, he declared, “I’ve done everything for this woman. I’ve paid for her room, bought her food, and paid installments on her car.”

In his mind, his financial contributions entitled him to beat her. The terrified witnesses watched as he drew his revolver and beat her over the head until she stopped moving. Then he fired two shots into the floor. Grace did not flinch. She was dead.

Once Nolan’s rage subsided, Wilson, Balfe, Smith, and Riley cautiously approached him. He allowed himself to be escorted to his second-floor room. He muttered the entire way that he loved Grace, but her battered body told a different story—one of uncontrollable jealousy, rage, and bad booze. After arriving at his room, he downed several more glasses of gin, then he passed out on the floor.

Nolan was charged with murder.

Grace’s two daughters, Edna (17) and Mary Jane (14) visited “Daddy” Nolan in jail. Sobbing in grief or self-pity, Nolan wrapped his arms around the girls. The girls told officers he was always good to them. A judge denied Nolan permission to enter an insanity plea, and jury selection began on November 9th. With several eye-witnesses to the fatal beating, it didn’t seem Nolan had much of a chance to beat the rap. Helen testified Nolan was in a frenzied rage when he cornered Grace.

Attorneys for Nolan tried twice more to get permission to enter an additional plea of not guilty by reason of insanity, but the judge denied the motions. When the insanity plea went nowhere, Nolan took the stand and said that he had no memory of anything after he threw Grace out of his room.

Following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced Nolan to life. He was lucky; the prosecution wanted him to hang.

Nolan entered San Quentin on January 9, 1932. He gave his profession as prop man. Disgraced cops are not welcome If he was smart, Nolan never mentioned his decade on the Los Angeles Police Department to his cellmates.

On February 1, 1932, the State Board of Prison Terms and Paroles denied Nolan’s request for release. The Board informed him he would have to serve 10 calendar years before they would review his application again.

They released Nolan in early March 1942. He did not enjoy his freedom for long. He died on July 20, 1943 in a VA facility in San Francisco.

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

Still breathing, Christ was rushed to the Georgia Street Receiving Hospital where he died on the operating table.

Still breathing, Christ was rushed to the Georgia Street Receiving Hospital where he died on the operating table.