This is a big month for the Deranged L.A. Crimes blog. On December 17, 2012, the 110th anniversary of the birth of the woman whose career and life inspires me, Agness “Aggie” Underwood, I started writing this blog. I also authored her Wikipedia page, which was long overdue.

By the time I began, Aggie had been gone for twenty-eight years. I regret not knowing about her in time to meet her in person. But, through her work, and speaking with her relatives over the years, I feel like I know her. I have enormous respect for Aggie. She had nothing handed to her, yet she established herself in a male-dominated profession where she earned the respect of her peers without compromising her values. She also earned the respect of law enforcement. Cops who worked with her trusted her judgement and sought her opinion. It isn’t surprising. She shared with them the same qualities that make a successful detective.

This month, I will focus on Aggie. I want everyone to get to know and appreciate her. She was a remarkable woman.

Agness “Aggie” Underwood never intended to become a reporter. All she wanted was a pair of silk stockings. She’d been wearing her younger sister’s hand-me-downs, but she longed for a new pair of her own. When her husband, Harry, told her they couldn’t afford them, she threatened to get a job and buy them herself. It was an empty threat. She did not know how to find employment. She hadn’t worked outside her home for several years. A serendipitous call from her close friend Evelyn, the day after the stockings kerfuffle, changed the course of her life. Evelyn told her about a temporary opening for a switchboard operator where she worked, at the Los Angeles Record. The job was meant to last only through the 1926-27 holiday season, so Aggie jumped at the chance.

Aggie arrived at the Record utterly unfamiliar with the newspaper business, but she swiftly adapted and it became clear to everyone that, even without training, she was sharp and eager to learn. The temporary switchboard job turned into a permanent position.

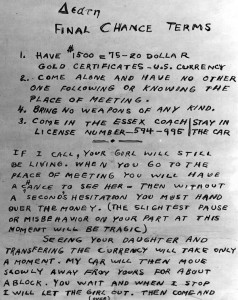

In December 1927, the kidnapping and cruel mutilation murder of twelve-year-old schoolgirl Marion Parker horrified the city. Aggie was at the Record when they received word the perpetrator, William Edward Hickman, who had nicknamed himself “The Fox,” was in custody in Oregon. The breaking story created a firestorm of activity in the newsroom. Aggie had seen nothing like it. She knew then she didn’t want to be a bystander. She wanted to be a reporter.

When the Record was sold in January 1935, Aggie accepted an offer from William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper, the Evening Herald and Express, propelling her into the big leagues. Working for Hearst differed entirely from working for the Record. Hearst expected his reporters to work at breakneck speed. After all, they had to live up to the paper’s motto, “The First with the latest.”

From January 1935, until January 1947, Aggie covered everything from fires and floods to murder and mayhem, frequently with photographer Perry Fowler by her side. She considered herself to be a general assignment reporter, but developed a reputation and a knack for covering crimes.

Sometimes she helped to solve them.

In December 1939, Aggie was called to the scene of what appeared to be a tragic accident on the Angeles Crest Highway. Laurel Crawford said he had taken his family on a scenic drive, but lost control of the family sedan on a sharp curve. The car plunged over 1000 feet down an embankment, killing his wife, three children, and a boarder in their home. He said he had survived by jumping from the car at the last moment.

When asked by Sheriff’s investigators for her opinion, Aggie said she had observed Laurel’s clothing and his demeanor, and neither lent credibility to his account. She concluded Laurel was “guilty as hell.” Her hunch was right. Upon investigation, police discovered Laurel had engineered the accident to collect over $30,000 in life insurance.

Hollywood was Aggie’s beat, too. When stars misbehaved or perished under mysterious or tragic circumstances, Aggie was there to record everything for Herald readers. On December 16, 1935, popular actress and café owner Thelma Todd died of carbon monoxide poisoning in the garage of her Pacific Palisades ho9me. Thelma’s autopsy was Aggie’s first, and her fellow reporters put her to the test. It backfired on them. Before the coroner could finish his grim work, her colleagues had turned green and fled the room. Aggie remained upright.

Though Aggie never considered herself a feminist, she paved the way for female journalists. In January 1947, they yanked her off the notorious Black Dahlia murder case and made her editor of the City Desk, making her one of the first woman to hold this post for a major metropolitan newspaper. Known to keep a bat and startup pistol handy at her desk, just in case, she was beloved by her staff and served as City Editor for the Herald (later Herald Examiner) until retiring in 1968.

When she passed away in 1984, the Herald-Examiner eulogized her. “She was undeterred by the grisliest of crime scenes and had a knack for getting details that eluded other reporters. As editor, she knew the names and telephone numbers of numerous celebrities, in addition to all the bars her reporters frequented. She cultivated the day’s best sources, ranging from gangsters and prostitutes to movie stars and government officials.”

They were right. Aggie dined with judges, cops, and even gangster Mickey Cohen. I hope you will enjoy reading about Aggie, as much as I will enjoy telling her stories.

Joan

![Mariion, Mrs. Parker, Marjorie. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/00027810_marianfamily-300x229.jpg)

![William Edward Hickman [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/00027382_hickman-222x300.jpg)