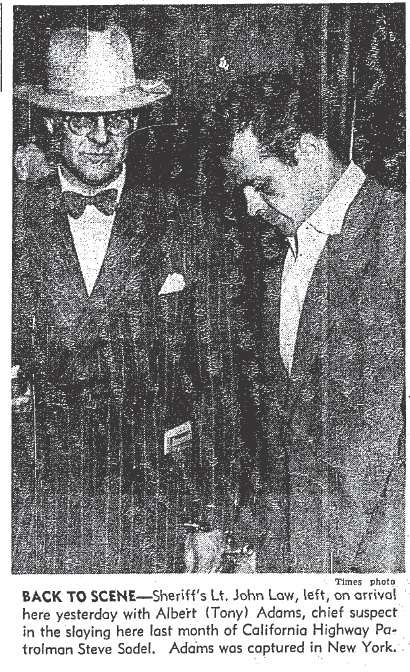

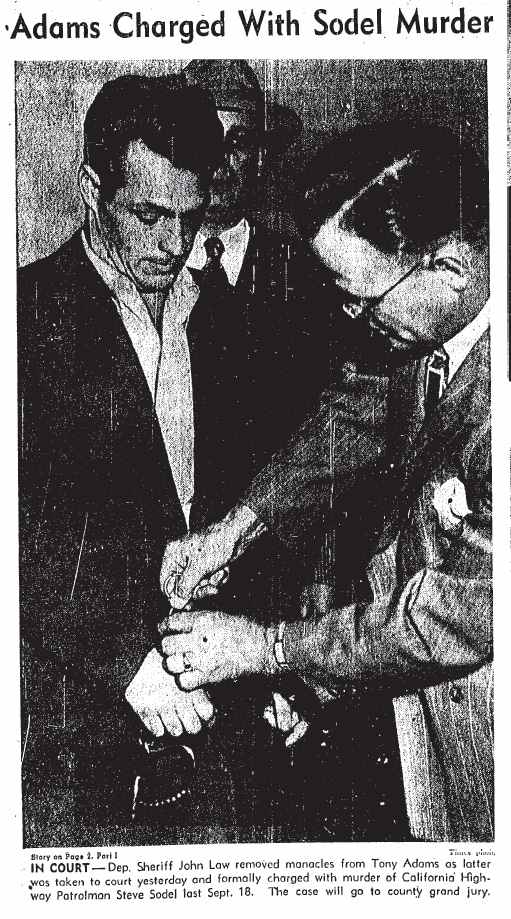

On October 24, 1946, Tony Adams limped into Judge Leroy Dawson’s courtroom and was formally charged with the murder of California Highway Patrolman Steve Sodel. He was also indicted for grand theft of the Chevy sedan which belonged to Jeanne Trude. Adams was manacled to Lieutenant John Law of the sheriff’s department, presumably to prevent him from making another escape attempt. Adams’ attorney, William E. Turner, waived reading of the complaint and Judge Dawson set a hearing date.

On October 24, 1946, Tony Adams limped into Judge Leroy Dawson’s courtroom and was formally charged with the murder of California Highway Patrolman Steve Sodel. He was also indicted for grand theft of the Chevy sedan which belonged to Jeanne Trude. Adams was manacled to Lieutenant John Law of the sheriff’s department, presumably to prevent him from making another escape attempt. Adams’ attorney, William E. Turner, waived reading of the complaint and Judge Dawson set a hearing date.

Adams, an occasional artist’s model, had at least one person in his corner. Beverly Lounsbury, 23, ex-cashier at a Sunset Strip night club that was one of Adams’ regular night spots. Lounsbury visited Adams in the County Jail on the morning of his arraignment. She said that Adams had broken a date with her for the night before Sodel’s murder. Lounsbury told Lieutenant Law, “I feel sorry for him and wanted to tell him so. He told me you fellows didn’t believe him when he said he threw the gun away but he swore he was telling the truth.”

A jury of nine women and three men was selected to determine Adams’ fate. Attorney William Turner must have worked hard to get nine women on the jury. There was no doubt that Adams was a handsome guy, referred to in the newspapers at the Playboy Killer. Perhaps, if he was lucky, the women jurors could be swayed by the defendant’s good looks. Adams was going to need all the luck he could get. He had drawn Judge Charles W. Fricke. The judge was a former prosecutor with a reputation for being a tough on lawbreakers. For their part, the prosecutors John Barnes and Fred Henderson didn’t care what Adams looked like, they made it clear that they intended to seek the gas chamber for the alleged cop killer.

Beverly Lounsbury found a seat in spectator section of Fricke’s courtroom. She told reporters “I’m not sure myself that Tony is guilty of the crime they charge him with. He needs a friend and I’m going to stick by him.”

One of the prosecution witnesses was a former girlfriend of Adams’, Jeanne Louise Smith. The car hop testified that she and Adams had dated briefly while she was separated from her husband. On the evening of September 14, Adams had shown up at her workplace to show her something. “He called me to the rear of the drive-in stand and showed me this gun. I asked him what he was doing with it, but he didn’t answer. He merely stood there, holding the gun in one hand and jingling a bunch of cartridges in his other hand.” Unfamiliar with guns, Smith was shown several different types of firearms but she was unable to say whether Adams had shown her a revolver or another type of gun.

Frances Sodel, the slain officer’s widow, took the stand and, wiping away tears, she identified a photo of her husband and articles of clothing which were discovered in the shallow grave with Steve Sodel’s bullet riddled body.

Frederic D. Newbarr had performed the autopsy on Sodel and he testified that the officer had been shot in the chest five times.

Jack Singleton identified Adams as the man who had stopped him and asked for help in extricating his car from sand alongside the road. Singleton said he had a feeling that the car was hot, so when he saw Officer Sodel he flagged him down and reported his suspicions. Sodel took off after the black sedan.

In his testimony service station operator John Rose said “I heard sounds of automobiles traveling at a high rate of speed and then a black Chevrolet zoomed east on Jefferson closely followed by a California Highway Patrol car. Neither car made the boulevard stop and I think they were going about 65 or 70 miles an hour. I knew the Highway patrol car was Sodel’s because I had seen it many times before.” Rose said he watched both cars disappear from view, then he went back to work.

Jeanne Trude and Elyse Pearl Brown

Jeanne Trude told the court how Adams had introduced himself to her and a girlfriend, movie extra, Elyse Pearl Brown, at the Jococo Club. She said Adams accompanied them to Dave’s Blue Room on the Sunset Strip where, “Miss Brown and myself ordered dinner at Dave’s but Tony just asked for a cup of coffee. He said he was suffering from malaria. Then he excused himself and left. I didn’t see him again, but when I went to get my car I discovered it was gone. I saw it again two weeks later and instead of being gray it was painted black–and not very well, at that.”

The hat-check girl/former cashier and reputed girl friend of the defendant testified that he had visited her a couple of days prior to the slaying. He had a gun, a handful of cartridges and an electric razor he claimed he had won in a poker game the previous night. Adams wanted her to hold the gun for him but she refused. He then told her to “keep quiet about the whole thing.”

One of Adams’ neighbors, Gordon Briggs, testified that he had seen him wearing a paint stained work shirt late in the afternoon of September 17. When Briggs asked about the stains Adams told him, “I’ve been helping a friend fix some pipes.”

Adams’ explanation for the paint was refuted by Police Chemist Ray Pinker. Pinker said he took samples of paint from the stolen car and matched them to the paint on Adams’ work shirt. They were identical. Pinker had also examined the undercarriage of the stolen car for evidence and had found weeds similar to those found near Sodel’s shallow grave.

Adams’ defense opened their case with two alibi witnesses. The first was Armand Martinez who worked at a cafe at 219 N. Vermont Avenue. He told jurors that Adams couldn’t have committed the murder because he was in the cafe lunching with a beautiful blonde at the time of the crime.

Next on the witness stand was Alvin Faith, a bartender. At 3 p.m. on the day of Sodel’s disappearance he said that Adams was in his bar. “Adams had a nosebleed. So I got him some ice and told him to go back to the restroom.”

Fletcher Herndon, an employee of the Studio Club at 3668 Beverly Boulevard, said that Adams was a frequent customer and had been in at about 11 p.m. on September 17 and asked whether a woman named Selznick had been in looking for him. Selznick?! At the mention of the name name Adams grimaced at Herndon and began to shake his head vigorously back and forth. Herndon didn’t get the message fast enough. He said it was his understanding that the woman was married to a “movie man”. Is it possible that Irene Mayer Selznick, wife of producer David O. Selznick, was seeing pretty boy Tony Adams? In Hollywood, anything is possible.

Adams’ attorneys decided to put their client on the stand to testify in his own defense. Under direct examination by William Turner, Adams denied being Sodel’s killer. Once Turner had finished Prosecutor John Barnes grilled Adams in a blistering cross-examination.

The only thing Adams would admit to was that he had accompanied Jeanne Trude from the Jococo Club to Dave’s Blue Room. He claimed that he left the table when he realized he didn’t have funds sufficient to pay for dinner. Rather than face the embarrassment, he left. In the parking lot Adams claimed he met a “Mr. Cudahy”–a guy he knew from one of the bars in town–and they’d driven downtown looking for women to pick up.

According to Adams, the mysterious Mr. Cudahy told him he as leaving for New York the next evening and offered Adams a ride. They arranged to meet the next day. Adams said they drove to Las Vegas, but he discovered Cudahy was carrying a box filled with guns. Adams said he “ditched” Cudahy and went on to New York by bus. He told the court “The first time I knew I was wanted for any crime was when I heard it over the radio on a murder program. When my name was mentioned you could have knocked me through the floor.”

Adams claimed the statements he’d made to New York City detectives, in which he had copped to stealing Jean Trude’s car and getting rid of two guns the day following Sodel’s murder, had been made under duress. Adams said he was questioned continuously by a group of at least 6 detectives. One of them, he said, kept slamming a blackjack on the table and telling Adams that he was a candidate for Harts Field (a local pauper’s cemetery in).

In closing arguments the prosecutors wove together all of the circumstantial evidence that linked the defendant to the murder. They made a compelling case.

The Defense Attorneys John Irwin and William Turner weren’t left with much. All they could do was maintain that the State had failed to prove its case. They said that there was no definite link between Adams and the murder of Steve Sodel.

The jurors would have to weigh the evidence and testimony and make up their own minds.

The jury deliberated for four hours before notifying Judge Fricke that they had reached a verdict. Frances Sodel said beside another CHP widow, Mrs. Loren Roosevelt as they waited for the verdict to be read. Adams, dressed in a brown pin-striped suit, sat at the defense table with his head in his hands. Jury foreman Edward A. Mohr handed the decision to the court clerk, who then handed it to Judge Fricke. Adams was found guilty of the murder of Steve Sodel. But rather than the gas chamber the jury recommended life without parole.

Why hadn’t the jury handed Adams, a cold-blooded cop killer, a ticket to California’s gas chamber? Evidently the verdict was a compromise, reached when one of the female jurors declared that she would, “sit in the jury room for six months if if necessary” rather than condemn Adams to death.

After hearing the verdict, Adams posed for news photographers and said, “I am satisfied with the jury’s verdict. My attorneys, Richard Erwin and William Turner, have given me a fair shake. I’m very lucky.”

Certainly luckier than Steve Sodel and his family.

Epilogue — According to records, Tony Adams arrived at San Quentin on February 1, 1947. Adams’ prison register indicates that he was married with one child. His marital status never came up at trial, although his numerous girlfriends and other female acquaintance did. It is entirely possible that he abandoned his wife and child, likely in New York. One wonders if his wife and child ever knew where he went or what happened to him. Adams didn’t spent much time at San Quentin before being transferred to Folsom Prison on April 17, 1947. As far as I know he remained there until he was paroled. I haven’t been able to discover the date of his parole, but I sincerely hope his looks were long gone by the time he was released. He had a reputation for using women by trading on his looks. Several women to whom he owed money came forward to talk to sheriff’s department detectives. I prefer to believe that by the time he left prison he had nothing left to trade. Albert Anthony Adams died in Huntington Beach, California on August 15, 2000.

A bronze memorial plaque honoring Steve Sodel was set in cement at the base of a tree at the Sheriff’s Honor Farm (known as Wayside) in Castaic by Sheriff’s Department American Legion Star Post 309.

Note: Many thanks to my friend, Mike Fratantoni, for sharing this story with me.

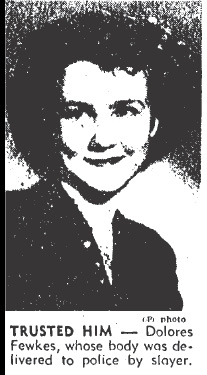

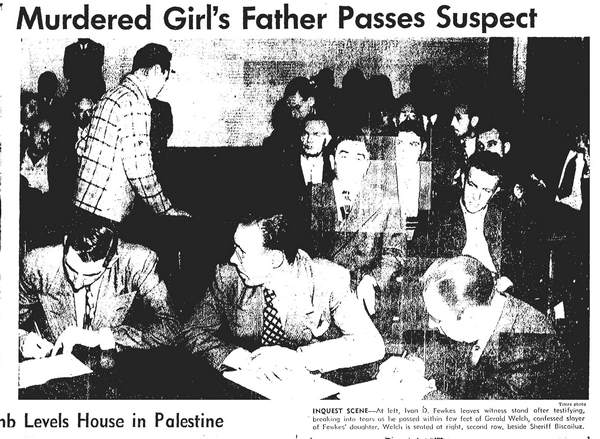

Gerald Welch confessed to killing Dolores Fewkes claiming that it was a suicide pact gone wrong. Sheriff’s investigators, Detective Sergeant Charles Gregory and his partner, L.E. Case, took him out to the lonely picnic ground where the crime had occurred for a reenactment. The place was peaceful, tucked away in a grove of tall pine treees. The picnic bench where Dolores had been shot was stained with her blood and so was the sandy soil beneath it.

Gerald Welch confessed to killing Dolores Fewkes claiming that it was a suicide pact gone wrong. Sheriff’s investigators, Detective Sergeant Charles Gregory and his partner, L.E. Case, took him out to the lonely picnic ground where the crime had occurred for a reenactment. The place was peaceful, tucked away in a grove of tall pine treees. The picnic bench where Dolores had been shot was stained with her blood and so was the sandy soil beneath it.

A few days following her death the 16-year-old was placed in an open casket surrounded by several large floral wreaths. Her funeral was held in North Long Beach and she was laid to rest in Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier. At least Gerald’s request to a judge to be allowed to attend her funeral had been denied. Her parents and surviving siblings were suffering enough without having to share one of the worst days of their lives with Dolores’ killer.

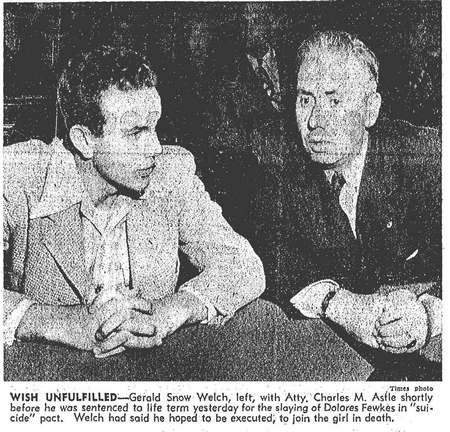

A few days following her death the 16-year-old was placed in an open casket surrounded by several large floral wreaths. Her funeral was held in North Long Beach and she was laid to rest in Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier. At least Gerald’s request to a judge to be allowed to attend her funeral had been denied. Her parents and surviving siblings were suffering enough without having to share one of the worst days of their lives with Dolores’ killer. The all-day hearing in Judge Fricke’s court began with Gerald pleading guilty to murdering Dolores. The judge read letters written by Dolores to Gerald. One of them was a poignant reminder of Dolores’ youth. Her declaration of love was surrounded by biology class doodles and it read: “I told you once that I could never love another guy and I still mean it. What good is loving a guy when he doesn’t love you enough to care whether he hurts you or not?” Like most high school girls in 1947 she dreamed of marriage. Among her notebook scribbles she had practiced signatures “Mrs. Jerry Welch,” Mrs. Dolores Welch” and “Mrs. G.S. Welch.” Fraught with the expected teenage angst, another of Dolores’ letters to Gerald read: “I’ll tell you what I expected of you. I wanted you to see me as much as possible, to think about me as much as I do you–to not want to go anywhere without you, but it was impossible. These few things would have kept me happy, happy just to know that you don’t enjoy doing things without me. I guess it didn’t work out. I don’t know what you are going to do, but as for me, I’ll probably go on living in a rut, going to school, then to college. I’ll never ever be seen with another one unless it is you. Unless you think you want me bad enough to make me happy, I’ll wait for you forever if I have to. Yours forever, Dolores”

The all-day hearing in Judge Fricke’s court began with Gerald pleading guilty to murdering Dolores. The judge read letters written by Dolores to Gerald. One of them was a poignant reminder of Dolores’ youth. Her declaration of love was surrounded by biology class doodles and it read: “I told you once that I could never love another guy and I still mean it. What good is loving a guy when he doesn’t love you enough to care whether he hurts you or not?” Like most high school girls in 1947 she dreamed of marriage. Among her notebook scribbles she had practiced signatures “Mrs. Jerry Welch,” Mrs. Dolores Welch” and “Mrs. G.S. Welch.” Fraught with the expected teenage angst, another of Dolores’ letters to Gerald read: “I’ll tell you what I expected of you. I wanted you to see me as much as possible, to think about me as much as I do you–to not want to go anywhere without you, but it was impossible. These few things would have kept me happy, happy just to know that you don’t enjoy doing things without me. I guess it didn’t work out. I don’t know what you are going to do, but as for me, I’ll probably go on living in a rut, going to school, then to college. I’ll never ever be seen with another one unless it is you. Unless you think you want me bad enough to make me happy, I’ll wait for you forever if I have to. Yours forever, Dolores”