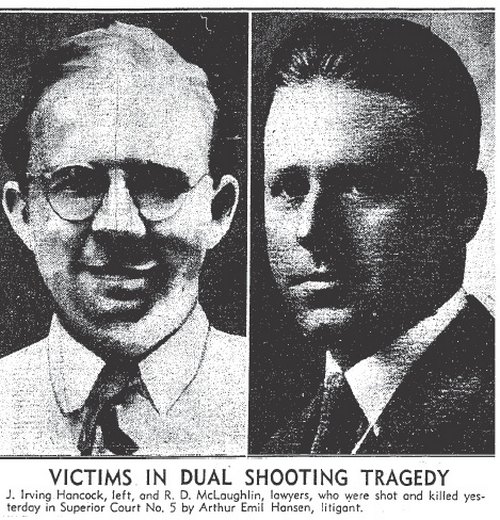

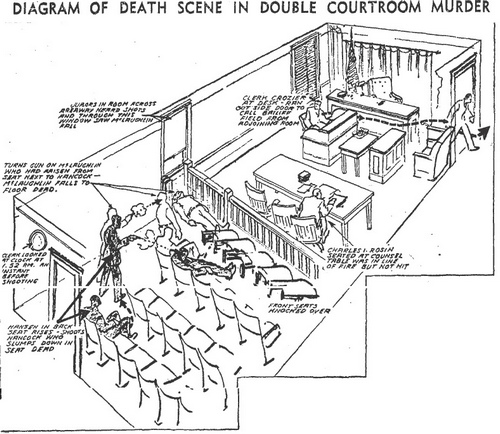

In 1939 Arthur Emil Hansen was sentenced to from two to twenty years in San Quentin for the courtroom slayings of two attorneys, R. D. McLaughlin and J. Irving Hancock, who were besting him in a civil suit that cost him every cent he had.

Did Arthur learn anything from the crime or his punishment? Evidently not, because in January 1951 a plan he’d hatched from behind the gray walls of San Quentin to assassinate four Los Angeles judges and two attorneys was uncovered by the Sheriff’s Department.

On Hansen’s list for liquidation were: Superior Judges Charles W. Fricke, Arthur Crumm and Frank G. Swain; Municipal Judge Lewis Drucker, former District Attorney Buron Fitts and Attorney Isaac Pacht. Apparently, Hansen had discussed his plan with a few of his fellow convicts — a big mistake–nobody will rat you out quicker. He had approached an inmate scheduled to be released on parole and offered to pay him $10,000 if he would murder one of the six men on his hit list.

Hansen’s plan was diabolically elegant in its own way. He wanted the parolee to whack one of the people on the list, then he would “take care” of the remaining five when he was paroled. He told his confidant that he intended to leave one clear fingerprint at the scene of each murder. Then, when the five murders had been committed, the police would have all the fingerprints of one of his hands and his identity would be revealed.

Hansen’s plan was diabolically elegant in its own way. He wanted the parolee to whack one of the people on the list, then he would “take care” of the remaining five when he was paroled. He told his confidant that he intended to leave one clear fingerprint at the scene of each murder. Then, when the five murders had been committed, the police would have all the fingerprints of one of his hands and his identity would be revealed.

Sounds a little crackpot, doesn’t it. But in the 12 years that Hansen had been in prison he’d become quite paranoid. He had little else to do but sit and stew about the real or imagined wrongs he’d suffered in the L.A. courts. He refused to accept blame for his actions and his rage continued to build to a detonation point.

Hansen gave his soon-to-be paroled friend a vitriolic letter, copies of which were to be given to various L.A. newspapers. The letter bitterly accused the judges, the Attorney General’s Office, the District Attorney and Governor Warren of conspiracy. Hansen’s letter also predicted that he would not be prosecuted for the murders because he would be revealed as an emancipator and a protector of the public.

I wonder if he thought he had super powers.

The letter advised the police that they could not save the victims on the hit list because “Their doom is sealed.” Hansen remained unrepentant for the double murders saying: “I regret nothing I did. I had nothing to lose.”

Hansen made a huge mistake when he directed that the letters be sent just as he was coming up for parole, He was just days away from being released when his plot was discovered. For the murder plot, Hansen forfeited all of his good time and at least six more years of his freedom.