In March 1951, Ruth Gmeiner, a United Press Staff writer, published a story about the growing problem of teenage drug addiction. Officials described heroin use as a “contagious disease.” A federal grand jury in Detroit reported they had uncovered shocking conditions . . . “Young people ranging in age between 14 and 21 have become confirmed and inveterate users of heroin.” Every big city noticed an uptick in the number of juveniles arrested on drug charges.

In Los Angeles, Robert Schoengarth started using heroin in 1948 as a student at North Hollywood Junior High School. He and a group of his friends grew marijuana in the Hollywood Hills. They weren’t entrepreneurs, they were pot philanthropists. What they didn’t consume themselves, they gave away to friends.

Raise your hand if you made stupid choices at 14. Yeah. Me too. Fortunately, my choices didn’t have lifelong consequences.

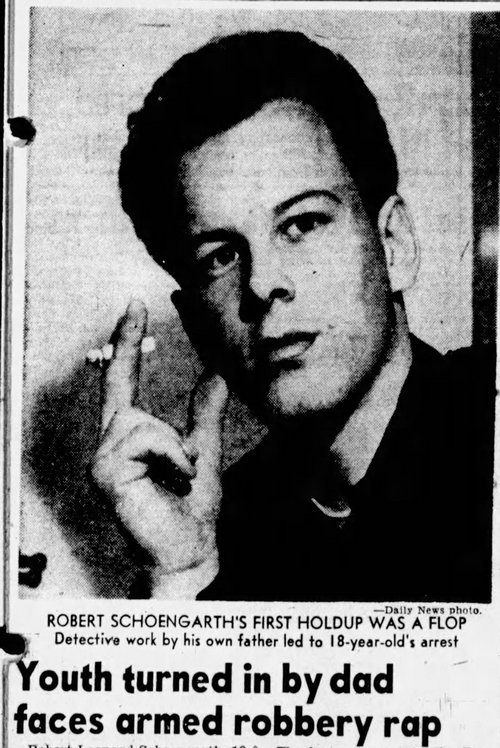

Late Wednesday evening, January 14, 1953, Morris Friedman worked behind the counter at his liquor store at 4100 Magnolia in Burbank. A dark-haired young man entered the store, bought a pack of cigarettes, and left. Moments later, he returned. He had a .22 in his pocket. He gestured at Friedman, “I want your money, sir.”

Friedman didn’t argue. He opened the cash register, grabbed a handful of bills, and handed them over. But the crook saw a few other bills in the drawer. He reached for them. Friedman grabbed the man’s arm, but the bandit pulled away and ran. The bandit was Robert.

Robert ran five blocks to his home. He replaced the gun, which belonged to his twin, William, in a dresser drawer. Passing through the living room where his father, Frank, spoke with a neighbor, he went into the front yard.

He called Frank from the house into the yard. “I told him I robbed the store.” It wasn’t Robert’s first brush with the law. Police arrested him twice before. Once for marijuana, and later for heroin. He spent time in the Los Angeles County Jail, and a California Youth Authority facility. He told his dad he’d been clean since his release. Frank didn’t believe him.

Robert said he couldn’t understand why he committed the robbery. He had a good job, making more than $62 a week as a mechanic’s apprentice. When Frank asked him for the stolen money, he gave it to him.

While Robert waited at home with his mother, Louise, for the police to arrive, Frank went to the liquor store and returned $33 to Friedman.

Patrolmen Ray Webb and Joe Mooney took Robert into custody. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” Robert said. “I suppose I have always been hanging around with the wrong crowd. That’s how I started using dope. Maybe they can put me in a hospital. Maybe it’d help me.”

Robert’s pain is palpable. So is Frank’s. Frank explained his actions by saying he wanted to help Robert, and that he feared that Robert’s twin brother, William, an aircraft worker, might be wrongly accused.

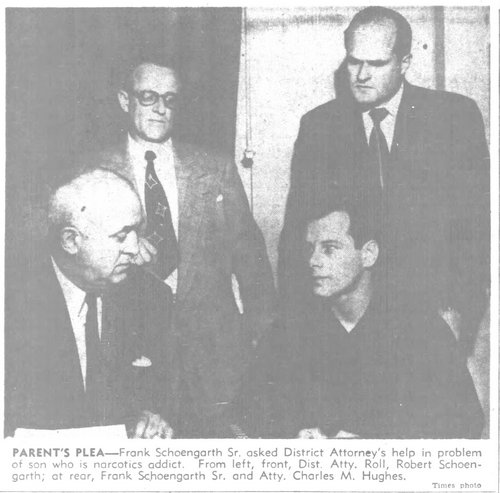

In desperation, Frank reached out to the well-known newspaperwoman, Florabel Muir. He spoke to her about Robert. “He really isn’t a bad boy. He started getting into bad company when he was in junior high school. It was then he started smoking marijuana. I didn’t know about it until he was arrested.”

Robert’s incarcerations did him no good. Frank said, “He’s only got worse with each sentence. I asked him the other night what in the world had happened to him and where he got the idea of taking a gun and sticking up somebody for money. He looked at me, sneered, and answered, ‘In jail. What do you think?’”

Back home for only a month, Robert seemed to do well. Then he asked to borrow $10. Frank couldn’t figure out why Robert would be broke right after payday—unless he was using drugs again. Robert denied it.

Frank hoped they wouldn’t return Robert to jail. He wanted him to go to a hospital for treatment. That would be up to the court. District Attorney Ernest Roll ordered a full investigation of Robert’s story. Robert told him he would “like to kick the habit if I got the chance.” He told Roll about his “graduation” from marijuana to heroin. The D.A. learned how easy it was for Robert to get high in a California Youth Camp. A friend supplied heroin through the mail.

In judge Charles Fricke’s court, Robert pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree robbery. The judge said he would place Robert in one of the California Youth Authority institutions for another chance at sobriety.

In less than two years, Robert was out of CYA and back in the news.

Police arrested him and his brother William on dope charges in February 1955. With them was a 17-year-old girl. The twins had their own place at 11920 Riverside Drive in North Hollywood. Police found a hypodermic needle kit and two caps of heroin. The girl told officers she went with Robert downtown to Temple Street, where they scored a gram of heroin from a dealer for $15.

Maybe the evidence was insufficient for prosecution, because by October Robert was again under arrest for drugs.

Police booked Robert and 18-year-old Rosalyn Berman after stopping their car on Emelita Street and Lankershim Boulevard. Robert drove erratically, and police noticed Rosalyn drop a packet from the car. Both had fresh needle marks on their arms and appeared to be under the influence.

Only 20-years-old, and Robert’s life was circling the drain.

Even after six years of addiction and legal woes, Robert was young enough to change the course of his life. Could he do it?

NEXT TIME: Robert’s story continues.