In her effort to prove that Clark Gable fathered her daughter, Gwendolyn, Violet mounted a vigorous media campaign. If you believed her story, he was the man who seduced and abandoned her 14 years earlier in a sleepy English village.

There was limited support for Violet’s fantastical tale. In fact, other than her immediate family (and even they weren’t enthusiastic), Violet’s only supporter was H. Newton, a Birmingham, England factory inspector.

In an interview with the London Daily Express, Newton confirmed that a man calling himself Frank Billings, who bore a striking resemblance to Gable, ran a poultry farm at Billericay “around 1918-1919”. The dates supplied by Newton were a few years earlier than Violet’s alleged affair.

Newton studied a photo of Gable and said,

“That either is Frank Billings or his double, even to the trick of folding one hand over the other. Yes, he has the same brow, nose, temples and twisted, cynical half-smile.”

Adding another layer of absurdity to the unfolding story was a penny postcard mailed from Tacoma, Washington. It read,

“Dear Sir—The lady is right—Frank Billings is the father of her child, but I am the man. Also am a perfect double for C.G.”

The perfect double from Tacoma did not come forward.

Several of Gable’s friends, acquaintances, and a former wife received subpoenas to appear in court. Among those supoenaed was Jimmy Fidler, a radio personality and journalist. Violet wrote to Fidler offering to sell him “for a price” the story of her affair with Clark Gable, the man she knew as Frank Billings.

Violet shared with Fidler her version of how Gable got his screen name. She wrote:

“In Billericay, Essex, England where I was wooed and won by a man known as Frank Billings, but who I now believe to be Clark Gable, this man told me of his love. I later learned, through pictures and a story in a film fan magazine, that he had changed his name to Clark Gable. It is my belief that he got his name in this way—our grocer, in Billericay was named Clark and he owned an estate he called The Gables. Hence Clark Gables.”

Yes, Violet frequently referred to the actor as Gables and was apparently unaware of his birthname, William Clark Gable.

The letters to Fidler weren’t the only ones Violet wrote. She attempted to correspond with Mae West, but West’s publicist, Terrell De Lapp, intercepted the missive during a routine vetting of Miss West’s incoming mail.

The letter received at Paramount Studio in January 1936 read:

“Dear Mae West—How would you like to be fairy godmother to Clark Gable’s child. Nothing could be more lovely than for you, Miss West, to be fairy godmother to my Gwendolyn, and put Clark Gable to shame.”

Despite Violet’s attempts to garner support from Fidler and West, and who knows how many others, Gable had no difficulty refuting her claims. He produced witnesses from the Pacific Northwest to prove that during the time he was allegedly impregnating his accuser, he was selling neckties and working as a lumberjack in Oregon.

Gable’s first wife, Josephine Dillon, was steadfast in her defense of her former spouse.

“Clark and I were married in December 1924. But I knew him the year before in Portland, Oregon when he attended my dramatic classes. To my knowledge, he has never been in England. It is sure he was not there in 1923 or 1924 when we were married, and, therefore, could not be the father of a 13-year-old girl born there at that time.”

Violet’s accusation was ludicrous, but on the plus side the trial afforded hundreds of women an opportunity to catch a glimpse of the man who would become The King of Hollywood. Secretaries and stenographers in the Federal Building held an impromptu reception for him. He autographed mementoes and chatted with them. They were in heaven.

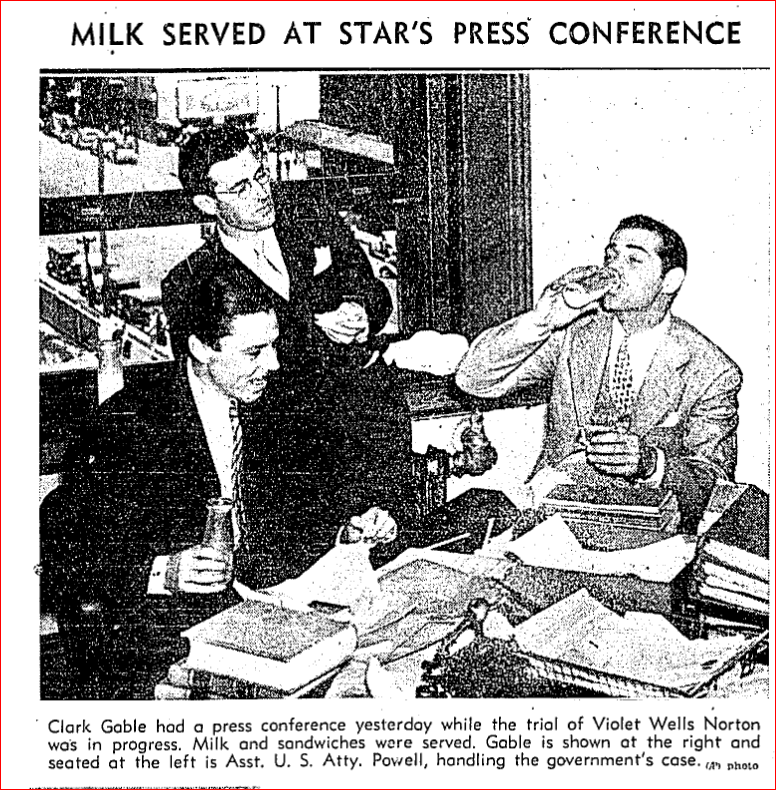

In the hallway prior to testifying, Gable chain smoked and appeared a little nervous. He told reporters:

“It’s my first court appearance. I don’t know what to expect.”

In court, Gable testified that he did not recognize the woman in court.

For her part, Violet remarked sotto voce to her attorney:

“That’s him. I’d know him anywhere.”

Courtroom spectators, keen to see Gable face his alleged progeny, were disappointed when he wasn’t required to appear during her testimony.

Judge Cosgrave wasn’t well-pleased that Gwendolyn was subpoenaed to appear.

“I regret that this witness has to be called at all, and I insist that her examination be limited only to extremely necessary points bearing on the charges in the indictment.”

Gwendolyn had nothing substantive to a add to her mother’s scheme—the girl was Violet’s pawn.

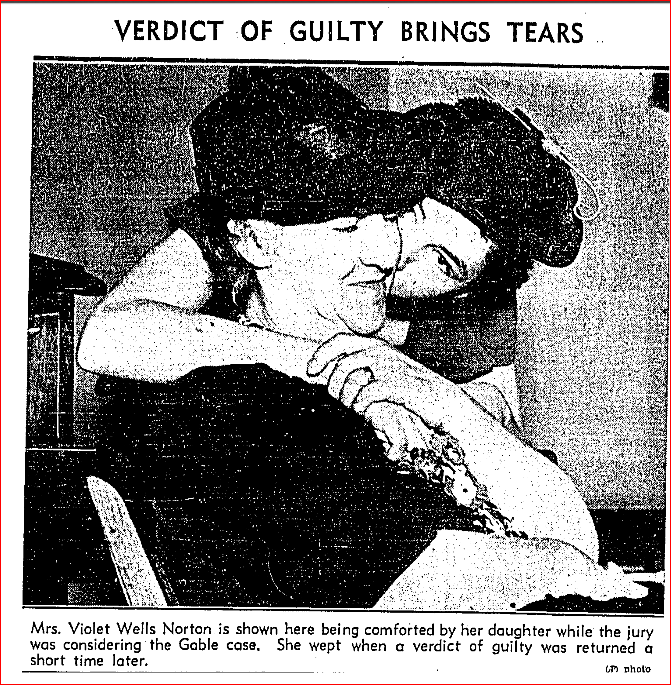

The jury began deliberations at 3:40 pm on April 23, 1937 and returned with their verdict at 5:20 pm. They found Violet guilty of fraudulent usage of the mails.

As Gwendolyn attempted to console her distraught mother, reporters reached Gable by telephone. He said:

“Of necessity, the woman’s charges were false, in view of the fact that I have never been in England and had never seen her until the trial began. It is unfortunate, of course, the she must come to grief in this manner, particularly because of her children.”

U.S. Attorney Powell, who prosecuted Violet, was not as understanding as Gable.

“This woman should be made an example, that men of Clark Gable’s type cannot be crucified in such a manner.”

Powell went on to describe Clark’s ascent to stardom:

“Clark Gable has pulled himself up by the bootstraps, out of an obscure background. He worked as a lumberjack, longshoreman, struggling actor, to achieve the ambition which drove him on to a $250,000-a-year salary.”

Attorney Morris Lavine, who would handle Violet’s appeals, defended her.

“She was simply calling to her sweetheart. She was sincere,” he said.

It is doubtful that Morris Lavine believed a word Violet said, but he was an attorney known to go the extra mile for a client. Violet was lucky to have him as her appeals attorney. (Lavine’s life and career in Los Angeles is a topic I’ll cover in future posts. He was a fascinating man and the self-described “defender of the damned.”)

The appeal Lavine filed on Violet’s behalf was nothing short of brilliant. He contended that her letter did not fall within the statute concerning mail fraud.

The court agreed with Lavine and ruled in Violet’s favor in October 1937. They characterized Violet’s plan as “a scheme to coerce or extort and is a species of blackmail.”

If local authorities had filed on Violet for blackmail or extortion she would have done more time.

In February 1938, following the success of her appeal, Violet faced deportation. An action was filed on the grounds that she had overstayed her visa and that she committed a crime involving moral turpitude. Lavine told reporters that Violet would stay with a sister in Vancouver.

Gwendolyn did not accompany her mother to Canada. She was placed in a private school by a local religious organization and was required to remain there until June.

Was Violet a greedy blackmailer or a delusional dreamer? We’ll never know for sure.

Clark Gable received thousands of fan letters over the course of his decades long career. Violet’s letter was an unwelcome anomaly. The adoring letter written to him by Judy Garland in the movie Broadway Melody of 1938 was probably a more accurate depiction of the kinds of letters he received.

As Judy writes she sings, ‘You Made Me Love You.” She performed the song earlier, in 1936, at Gable’s birthday party. It is one reason she got the part in the film which helped launch her career.