Gordon Stewart Northcott and his mother, Sarah Jane, fled to Canada to avoid arrest. But they weren’t on the run for long — they were busted in British Columbia. They unsuccessfully fought extradition to the U.S.

![Northcott, center, is shown shackled to Constable F. R. Rigby of the Canadian police. At the right is Corporal Walker Cruickshank, also a member of the Canadian police force. Northcott arrived in Los Angeles November 30, 1928, and was placed in the cell Hickman occupied at the County Jail. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/northcott-arrested_00027468.jpg)

Northcott, center, is shown shackled to Constable F. R. Rigby of the Canadian police. At the right is Corporal Walker Cruickshank, also a member of the Canadian police force. Northcott arrived in Los Angeles November 30, 1928, and was placed in the cell Hickman occupied at the County Jail. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Prior to being extradited to the U.S. to face murder changes Gordon gave his copyrighted story to the Vancouver Daily Sun, and it was a beaut.

Northcott said:

“There have been a lot of stories circulated about me. They are all untrue. What awful things to say about a man. Some people have been suffering from too much imagination, and a lot of people will be sorry when this case is cleared up.”

!["Poor little mother." Sarah Louise Northcott. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/louise-northcott_00027546-227x300.jpg)

No, it’s not Gordon in drag, it is his “Poor little mother”, Sarah Louise Northcott. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

Northcott went on to explain that his disappearance was only meant to shield his “poor little mother”:

“I had to protect poor little mother from this. I simply could not tell her of this. I simply could not tell her of what they were accusing me. If poor little mother had known of these charges it would have killed her.”

Poor little mother? Visualize for a moment the poor little mother wielding an axe and using the blunt end to bash in Walter Collins’ skull. THAT is the poor little mother to whom Northcott referred.

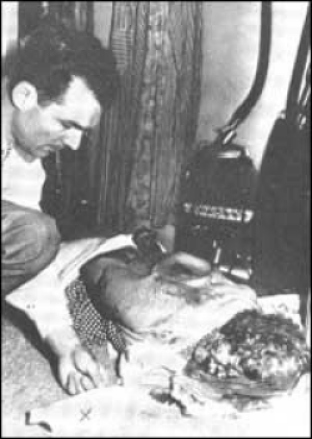

![J. Clark Sellers, criminologist, examines an axe which Sanford Clark says Mrs. Louise Northcott used in Walter Collins' murder. Rex Welsh, police chemist, declares the axe is stained with human blood. It was found in a chicken coop on the ranch. Northcott said he killed the boys with a gun. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm-axe_00027540-234x300.jpg)

J. Clark Sellers, criminologist, examines an axe which Sanford Clark said Mrs. Louise Northcott used in Walter Collins’ murder. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Northcott continued:

“So I kept it all from her, newspapers and everything I was forced to hide them. I wanted to get her away to a safe place. Then I intended to go back alone and fight this thing.”

Northcott’s statements to the press were as self-serving as one might expect, but what was interesting, and rather creepy, was the newspapers physical description of the child-slayer:

“Northcott is a good-looking youth, and has a disarming manner. His fair hair sweeps back in an easy wave from the parting on the left and there is a ready smile on his lips beneath his well-modeled nose. His eyes alone are peculiar. They are deep blue, but possess a fixed, staring quality, as if their owner is in a thrall.”

The papers even gave a description of Northcott’s traveling clothes. What was the well-dressed child serial killer wearing in 1928?

“On the train he wore a smartly cut brown tween suit with a dark brown stripe. His tie was brown with cream colored spots, and there was a thin brown strip in his shirt.”

The reporter failed to note Northcott’s primary accessory, shackles. He was firmly chained to the coach seat of the train that was returning him to California.

Dressed to the nines, and thoroughly enjoying his infamy, Northcott opined to the press on a variety of topics. He was particularly incensed about newspapers and pre-trial publicity:

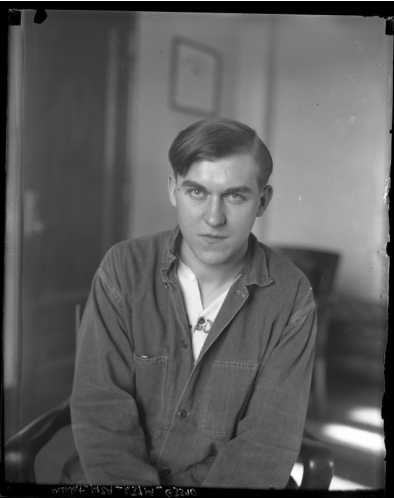

![Northcott sitting in his cell at the Los Angeles County Jail on December 1, 1928, the cell which was occupied by William Edward Hickman, the "Fox". Here he was relentlessly questioned. He said, "I'm a misfit, and once a misfit always a misfit." [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/northcott-jail-cell.jpg)

“I’m a misfit, and once a misfit always a misfit.” [Photo courtesy LAPL]

“The newspapers, especially those in the South, convict a man before he comes to trial. I do not think there should be so much publicity about crimes before the man charged with them goes into court.

I don’t blame the newspapers so much. They are in a competitive business. But I do blame the administration that permits the practice.”

The Hickman case was cited to him as an example of his contention.

“Oh, that was different,” he said, “Hickman deserved all he got.”

Once Gordon and his poor little mother were back in Los Angeles on U.S. soil, the pair promptly confessed to murder. But, no surprise, each quickly recanted their confessions.

Ironically, upon his return to the L.A. County Jail, Northcott would find himself in Cell No. 1 in Tank 10-B2 — the same cell that had been occupied for several weeks by William Edward Hickman, aka “The Fox”.

The most bizarre twist in the case had to have been when Christine Collins met Gordon Stewart Northcott in the County Jail to confront him about the murder of her son. Christine’s desire to believe that Walter was still alive was apparently so strong that she emerged from her conference with Northcott convinced that his denial to her that he had murdered her 9 year old son was the truth.

Christine would be Northcott’s most unlikely supporter.

A fool for a client.

Arrogance and stupidity ruled the day when Northcott discharged his counsel and chose to represent himself. As with most proverbs it’s difficult to find a precise attribution, but at some point in history a person, certainly an attorney, said: “I hesitate not to pronounce, that every man who is his own lawyer, has a fool for a client.”

![Jessie Clark. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/jessie-clark000274471-216x300.jpg)

Jessie Clark. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Northcott’s inept cross-examination of Sanford Clark was so detrimental to his own case that the prosecution never once offered any objections. Despite his abysmal peformance Northcott was supremely pleased with himself:

“I am not such a bad attorney after all, am I?” he asked reporters.

Gordon’s mother, Sarah Louise, surprised everyone when she suddenly decided to plead guilty to slaying Walter Collins! She seemed ready and willing to take responsibility for all of the atrocities committed in the Wineville chicken coop — but nobody ever believed that she was the sole villain behind the crimes; she was clearly attempting to save her son. Sarah was sentenced to life in San Quentin for Walter’s murder.

![Sarah Northcott on her way to prison. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/sarah-northcott_left-00027444-223x300.jpg)

Sarah Northcott on her way to prison. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Gordon’s trial continued but the outcome was a foregone conclusion; Gordon Stewart Northcott was found guilty of the murders of Lewis and Nelson Winslow and the so-called “headless Mexican” boy, and was sentenced to the gallows.

Northcott was hanged on October 2, 1930 at San Quentin. It’s said that he had to be supported during his climb up the thirteen steps, and then collapsed on the gallows. He was more or less rolled through the trapdoor where he strangled to death at the end of the noose. If that’s true it was no less than he deserved.

AFTERMATH

Gordon Stewart Northcott was convicted of three murders, but was suspected of as many as twenty. The children he kidnapped, sexually abused and murdered were killed in a chicken coop on his Wineville, California farm — which is why the slayings are often referred to as The Wineville Chicken Coop Murders.

![Chicken coops on the murder farm. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm_000274791.jpg)

Chicken coops on the murder farm. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

Christine Collins won a judgement of $10,800 [equivalent to $150,535.83 in current USD] against Captain J.J. Jones as a result of his having sent her to the psych ward when she refused to accept an impostor as her son. Collins would try more than once to collect from Jones — he would never pay her.

In fact, Captain Jones got off easy — the LAPD suspended him for four months without pay, and that was the extent of his punishment for what he’d done to Christine Collins.

Christine never stopped searching for Walter.

Arthur Hutchins, Jr., the faux Walter Collins, spent part of his adulthood selling concessions at carnivals. He eventually moved back to California as a horse trainer and jockey. He died of a blood clot in 1954, leaving behind a wife and young daughter, Carol. According to Carol Hutchins, “My dad was full of adventure. In my mind, he could do no wrong.

![Sanford Clark. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/sanford-clark00027503-238x300.jpg)

Sanford Clark. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

Sarah Louise Northcott, Gordon’s mother, was sentenced to life in prison but was paroled in May 1940. She died in 1944.

Sanford Clark, Northcott’s nephew, was never tried for any of the crimes at the farm. If he participated in any of the killings it was under the extreme coercion of his uncle.

Sanford was sent to Whittier Boy’s School for about two years. He impressed the staff with his desire to lead a productive life upon his release — which he did. He served in WWII, worked for the Canadian Postal Service, married and had children. He died in 1991 at the age of 78.

Wineville was so traumatized by the connection to Northcott that the city changed its name to Mira Loma on November 1, 1930, only a month after Northcott’s execution. However as recently as 2009 the house in which Gordon Stewart Northcott had lived was still there.

Northcott home.

http://www.americanghosttowns.us/Wineville.htm

POSTSCRIPT: This story of the Wineville Chicken Coop Murders is so twisted and complex that it is impossible to tell it all in just a few blog posts. I’ve covered it as well as I could given my constraints.

For Sanford Clark’s harrowing tale you may want to read THE ROAD OUT OF HELL. Another book on Gordon Stewart Northcott is NOTHING IS STRANGE WITH YOU. Be forewarned, any book that relates the full story is going to be a very tough read. The details are horrendous. A friend of mine is currently working on a book about the Northcott case, so there is more to come.

![Northcott, center, is shown shackled to Constable F. R. Rigby of the Canadian police. At the right is Corporal Walker Cruickshank, also a member of the Canadian police force. Northcott arrived in Los Angeles November 30, 1928, and was placed in the cell Hickman occupied at the County Jail. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/northcott-arrested_00027468.jpg)

!["Poor little mother." Sarah Louise Northcott. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/louise-northcott_00027546-227x300.jpg)

![J. Clark Sellers, criminologist, examines an axe which Sanford Clark says Mrs. Louise Northcott used in Walter Collins' murder. Rex Welsh, police chemist, declares the axe is stained with human blood. It was found in a chicken coop on the ranch. Northcott said he killed the boys with a gun. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm-axe_00027540-234x300.jpg)

![Northcott sitting in his cell at the Los Angeles County Jail on December 1, 1928, the cell which was occupied by William Edward Hickman, the "Fox". Here he was relentlessly questioned. He said, "I'm a misfit, and once a misfit always a misfit." [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/northcott-jail-cell.jpg)

![Jessie Clark. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/jessie-clark000274471-216x300.jpg)

![Sarah Northcott on her way to prison. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/sarah-northcott_left-00027444-223x300.jpg)

![Chicken coops on the murder farm. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm_000274791.jpg)

![Sanford Clark. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/sanford-clark00027503-238x300.jpg)

![Lewis and Nelson Winslow [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/winslows00027495.jpg)

![Northcott's murder farm. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm_00027479.jpg)