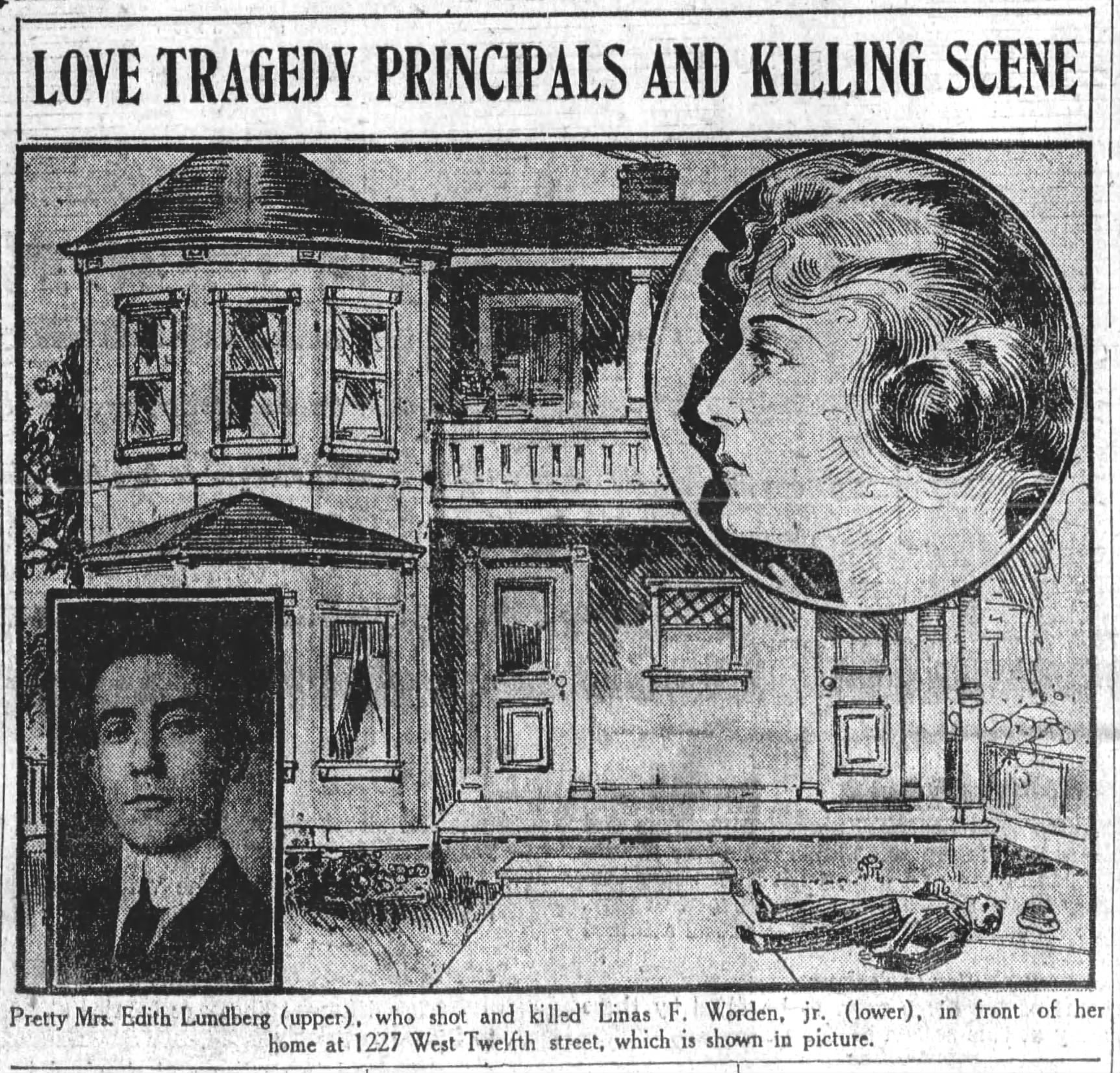

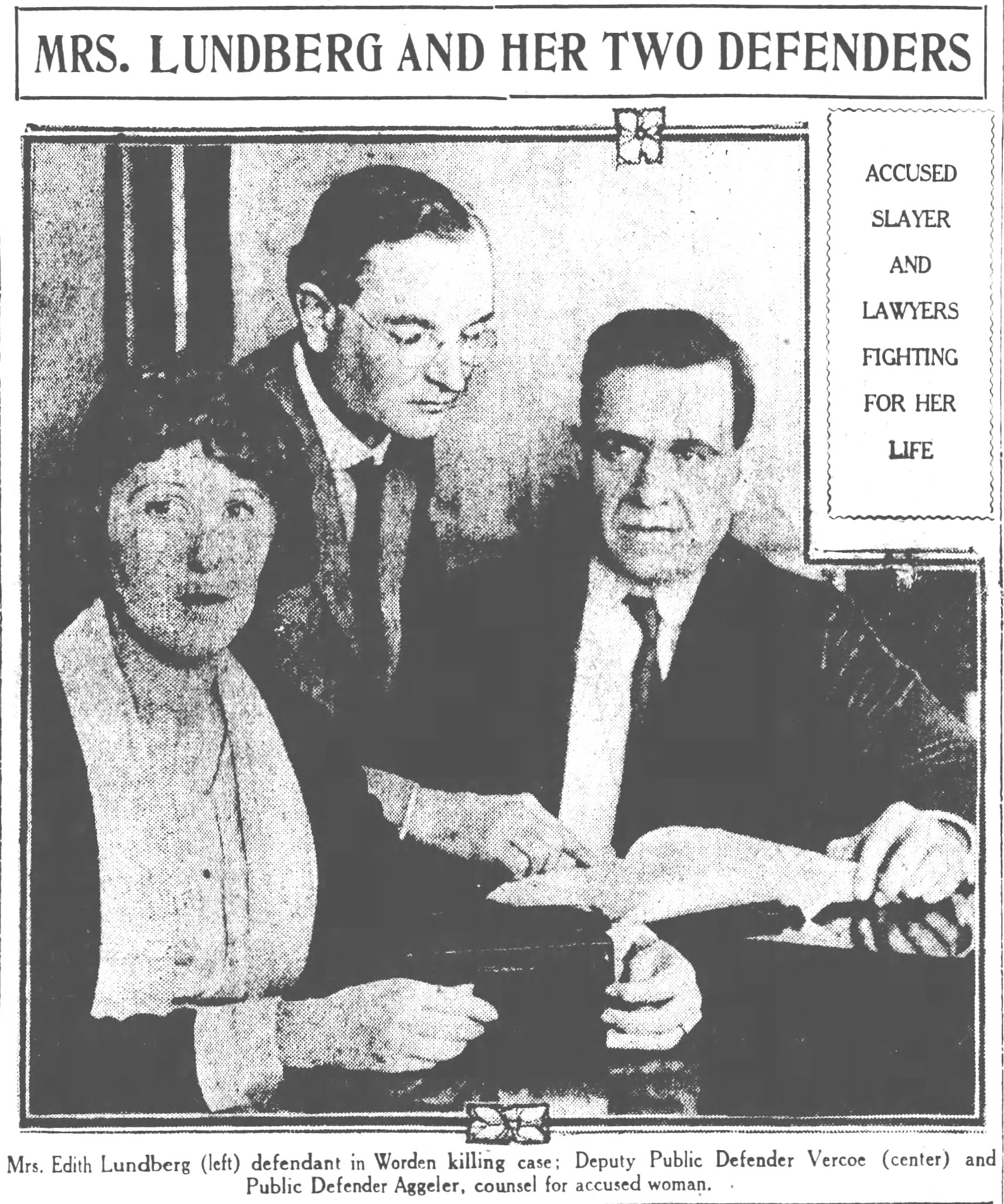

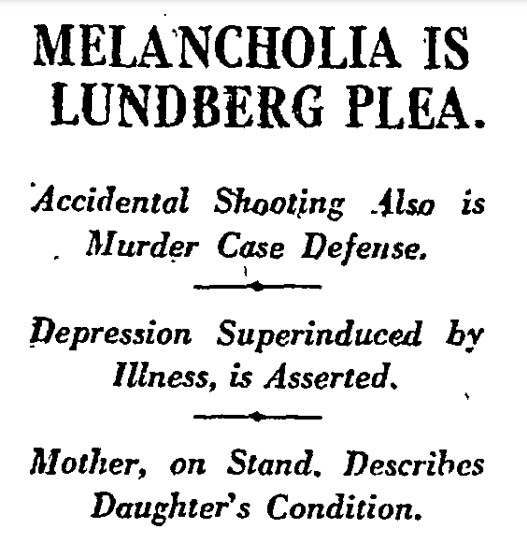

According to Edith’s public defender, William Aggeler, a state of extreme melancholia brought about by physical ailments suffered since childhood, account for her accidental shooting of Linus Worden, causing his death.

Edith’s mother recounted for the seven men and five women on the jury a litany of illnesses and conditions afflicting her daughter. She testified that at seven months old, Edith had a serious case of pneumonia; she had an attack of spinal meningitis at three; at nine they found her unconscious in a rocking chair. She remained in bed for several weeks and was in such extreme pain she couldn’t bear to be touched without screaming in agony. When she finally got out of bed, she held her head in a twisted position. A lump developed on the right side of her neck and when she walked, she dragged her right leg and complained of constant head pain. At twelve, she suffered a spasm so severe that her hands couldn’t voluntarily unclench.

After her marriage, at seventeen, her husband found her one afternoon unconscious lying between the bed and the wall. In the ten years since then, she endured many similar attacks, even having one while in jail.

In November 1920, Edith’s mother noticed her daughter’s extreme moodiness. She testified the nervous condition manifested itself in Edith’s refusal to eat and her inability to continue to work in any capacity. In the fall of 1920, her mother found a revolver in Edith’s room and removed it. She gave the weapon to her husband.

As sad as Edith’s life was, she still shot and killed a man—and that is the story the prosecution would tell. Detective Kline testified to his conversation with Edith in the hospital. He asked her how she came to be shot. She answered, “It does not make any difference.” He informed her of Linus’ death, and she said, “I shot him, but I do not believe he is dead and will not believe it until my brother-in-law, Lee, tells me so.”

Edith insisted mutual despondency was the reason for the shooting. She claimed both she and Linus wanted to die. The mutual destruction motive flew in the face of Edith’s initial statement, “I couldn’t live without him, and I couldn’t get along with him.”

Edith’s mother testified for the defense; however, her father, Mr. Vosberg, was called as a prosecution witness. His duty to testify weighed heavily on him. He loved Edith. He recalled for the jury the events of the night of Linus’ death. He said he and Harvey Clarke, his son-in-law, relaxed inside the house while Linus and Edith sat outside in Linus’ car. When they hear four shots, both men sprang into action. They found Linus dying, and Edith seriously wounded.

A packed courtroom heard Edith testify on Monday, July 25. Physical suffering made her life wretched, and she tried several times to commit suicide. Two years after she married, she tried it again. “I had been reading spiritualist books.” [Note: spiritualism was enormously popular following WWI. So many people lost loved ones and desperately wanted to contact them in the afterlife.] Edith said she read The Gateway of Heaven. “It described the experiences of a woman on the other side. After reading it, I got a desire to go and see what was there.”

The death of her husband exacerbated her depression. “I used to walk the palisades at Santa Monica and fight the inclination to go over. I did not think it was right at that time; I had a greater understanding then than later. I got the desire in August 1920 to take my life.”

A friend of hers from Santa Barbara shot himself in the head. She thought it would be “a good way to do it.” She bought a gun in early November.

Even jail didn’t stop Edith from attempting suicide. She got a hold of a pair of scissors and tried to do herself in.

Edith described suffering debilitating symptoms every month. She lived on aspirin. Often, she shut herself away in her bedroom.

Was there a legitimate medical cause for Edith’s physical complaint and behavior? It is possible Edith suffered from Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD). In the 1920s, the diagnosis didn’t exist. In fact, they didn’t add PMDD to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 2013, and it remains a controversial. Yet, the symptoms described by Edith fit the disorder. They also fit Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Her first suicide attempt at fourteen lends credibility to a hormonal imbalance, but that is speculation.

It isn’t surprising that Edith’s trial became a battle of expert witnesses. Alienists on both sides offered an opinion on Edith’s mental state. The question of her sanity loomed large.

Defense witness, Dr. Allen, believed Edith was insane at the time of the murder. In fact, he referred to her case as one of “psycopathic (sic) personality.” He said, “In considering her mental state, it is necessary to view it in the light of the history of her case. In this case, there is a very marked history of abnormality, or eroticism. I don’t think this woman was at any time mentally normal. Because of her physical condition, she was predestined to become mentally unbalanced in a crisis.”

Dr. Allen’s conclusion isn’t surprising given how often women were characterized as hysterical and insane.

I’ll digress for a moment. Women’s menstrual cycle has a long history of being misunderstood. In fact, the word taboo comes from the Polynesian word tapua, which means both sacred and menstrual flow. Ladies, if we ever learn to harness it, menstruation is our super power. Why? Ancient Romans believed a woman’s monthly flow could turn new wine sour, wither crops, dry seeds in gardens, kill bees, rust iron and bronze. Dogs who taste the blood become mad—their bite poisonous. There is some good news. Hailstorms and whirlwinds are driven away if menstrual fluid is exposed to flashes of lightning.

Don your capes and prepare for battle. Now back to Edith.

Edith’s conflicting stories of the murder are troubling. At first, she said Linus wanted to die. During her trial, she said it was an accident. Before she and Linus went out for a drive on the fatal night, she slipped into a small room off the parlor. Linus noticed her come and go twice before he asked her about it. She said she would explain later. She didn’t tell him it was where she kept her revolver. He didn’t see her slip the gun into her coat pocket.

When they returned later and sat in Linus’ car, Edith said she kept thinking about taking out the gun and shooting herself. She communicated some of her unease to Linus. He said he would see her the next night. Making future plans doesn’t sound like a man ready to kill himself.

Edith continued her testimony, “All kinds of emotions went through me. I remember him turning away from me. He laughed and said: ‘You will be all right.’ I shook my head and felt the gun. The first thing I knew there was a flash. I saw his face in front of me. The report frightened me.”

Did Linus laughing at her trigger a rage?

The defense hoped the jury would believe Edith’s ill health made her mentally irresponsible for Linus’ death.

“Many people suffer from illness, including headaches, but it doesn’t justify taking a life,” argued the prosecution. The D.A. asked the jury not to be swayed by “technical insanity,” nor sympathy, but to administer the law as it is written.

It took the jury an hour and a quarter to acquit Edith.

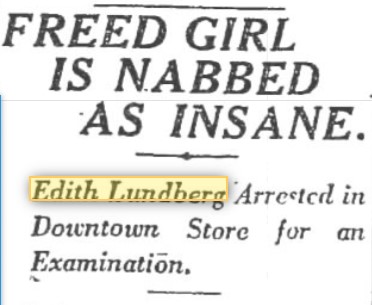

The following day, shortly after 2 PM, police rearrested Edith at a downtown department store on an insanity warrant sworn to by Detective Sergeant Eddie King of the district attorney’s office. Accompanying him was future LAPD chief, Louis Oaks. [Oaks served from 1922 to 1923 until they showed the hard-drinking the door. It’s an interesting tale for another time.]

Was the D.A. a sore loser? Maybe. But he pointed out that the attacks of melancholia Edith suffered were a recurrent affliction, and a recognized form of insanity.

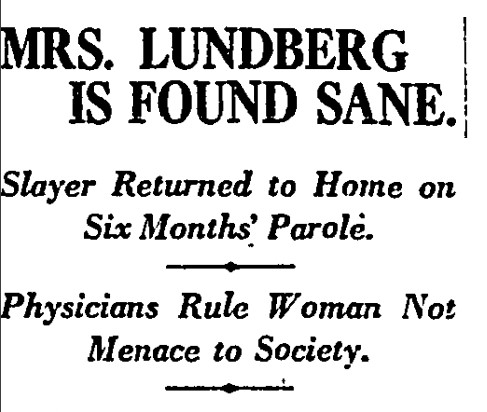

In early August, five physicians of the Lunacy Commission found Edith sane. While subject to depression, the doctors didn’t consider her a menace to society. However, they recommended six months of probation rather than confinement in an institution.

Judge Weyle said, “you have suffered enough.”

EPILOGUE

Following her acquittal, Edith resumed the use and spelling of her maiden name, Edythe Vosberg.

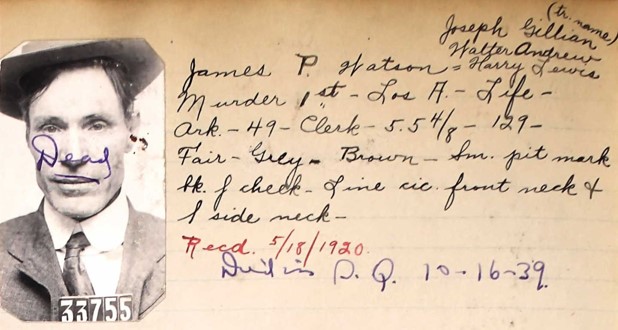

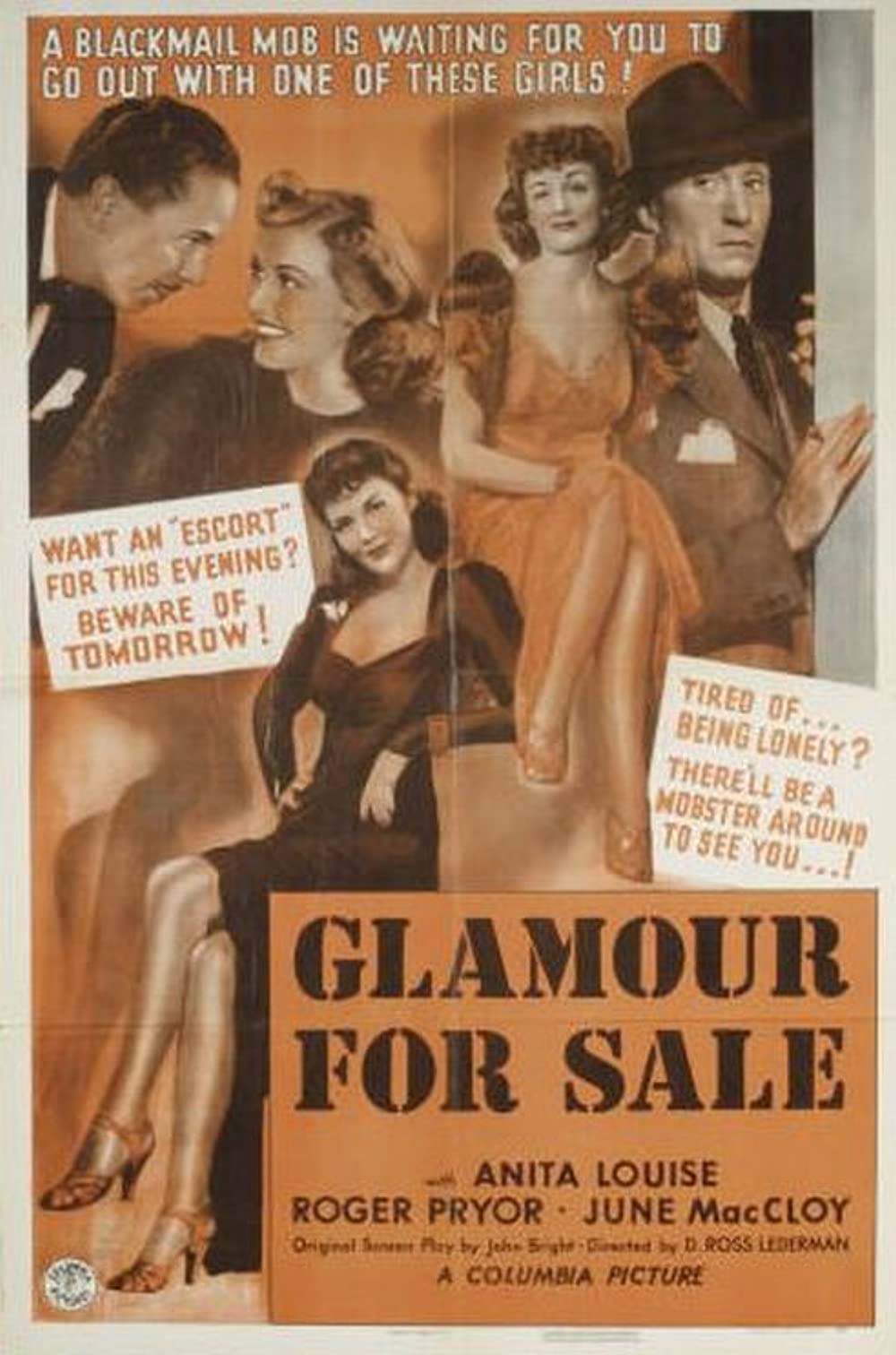

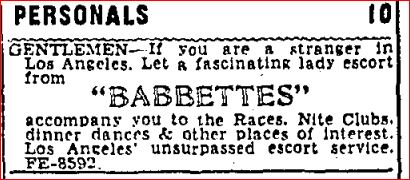

The 1930 census shows her living with her parents in a home at 858 N. Curson, in West Hollywood. She works as a stenographer in the motion picture industry. Her brother-in-law Harvey, and her brother Gayne (born Alfred D. Vosberg), worked as actors. Either of them may have helped her get the job. Her brother changed his name to Gayne Whitman after WWI to avoid the negative association with his German birth name. Gayne had a long career, from 1904-1957, he appeared in 213 films. On radio, he played the title role in Chandu the Magician and also worked as an announcer.

The 1933 city directory for Santa Monica, has Edythe working for the H.C. Henshey Company. Henshey’s was a major Santa Monica department store. Sadly, it went out of business years ago.

Edythe’s mother passed away in 1939. By the 1940 census, 49-year-old Edythe is living at 2630 St. George Street with her father and her nephew, 22-year-old Harvey Clark. The house is off Franklin Avenue, near the Shakespeare Bridge in Los Feliz.

In 1950, 56-year-old Edythe works as a record keeper for the city police department. It doesn’t say which city, she appears to be living in North Hollywood in the San Fernando Valley.

I don’t know what Edythe did from 1950 until her death in 1971. I know she never remarried, and never had any further run-ins with the law. She is buried at Forest Lawn in Glendale.