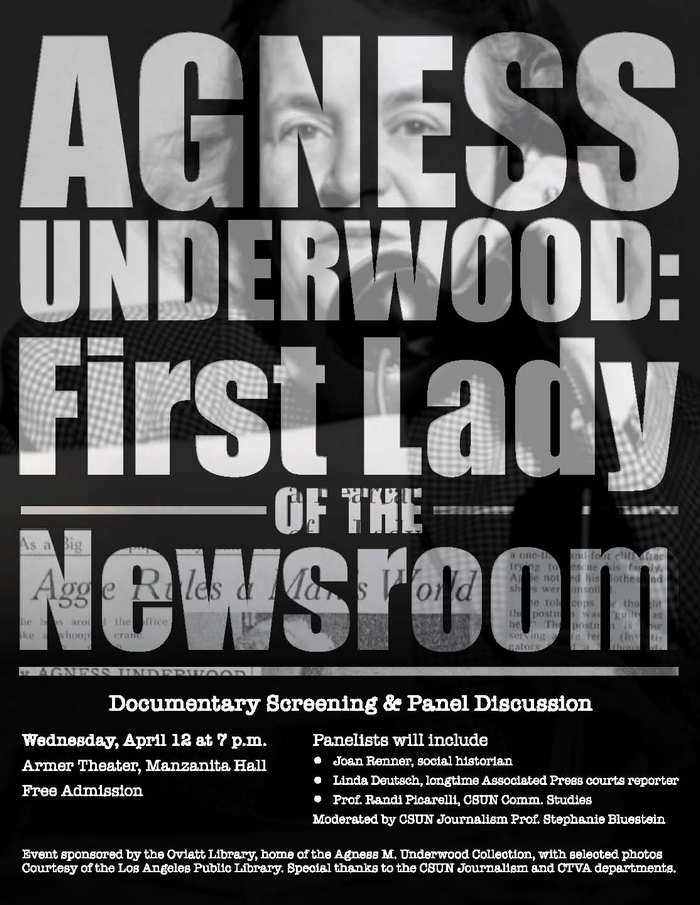

Please join Prof. Stephanie Bluestein, Linda Deutsch, Prof. Randi Picarelli, and me for the screening of a documentary and panel discussion on one of my favorite topics, newspaperwoman Aggie Underwood.

Frank Lovejoy with Betty Winkler and director, Himan Brown

From February 6, 1950 to September 25, 1952, Frank Lovejoy starred as Randy Stone in the NBC radio series Night Beat. The series was sponsored by Pabst Blue Ribbon beer and Wheaties breakfast cereal.

On September 18, 1950 at the end of the episode entitled Wanna Buy a Story? Frank Lovejoy was presented with an award by none other than Aggie Underwood. At the time Aggie was only a few years in to her post as City Editor of the Evening Herald and Express. Her autobiography, Newspaperwoman, had been out for about a year before this episode of Night Beat aired, and it was a great opportunity for her to plug the book.

According to Wikipedia, Ripperologist editor Paul Begg offered this description of the series:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

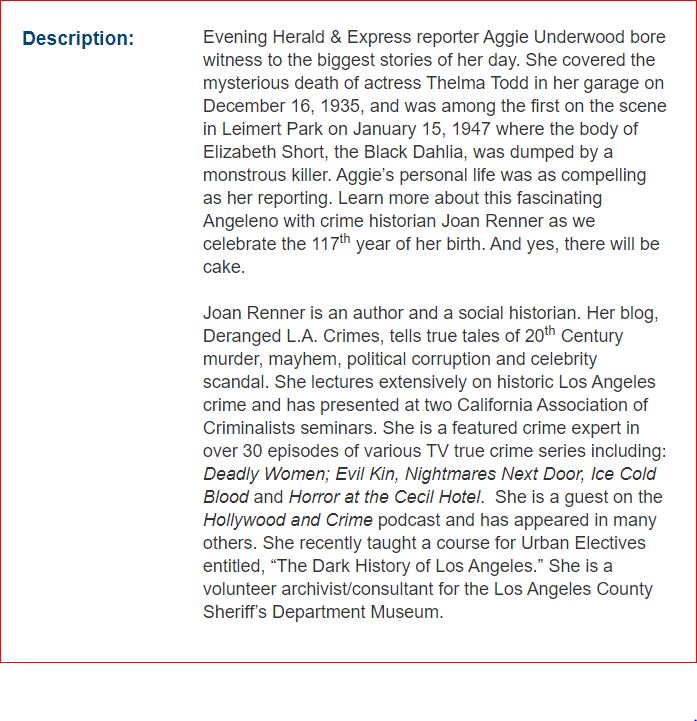

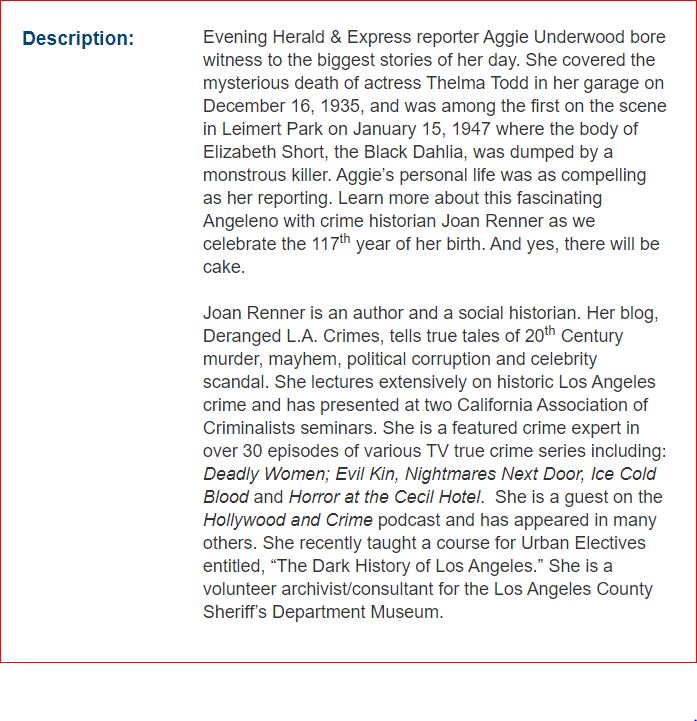

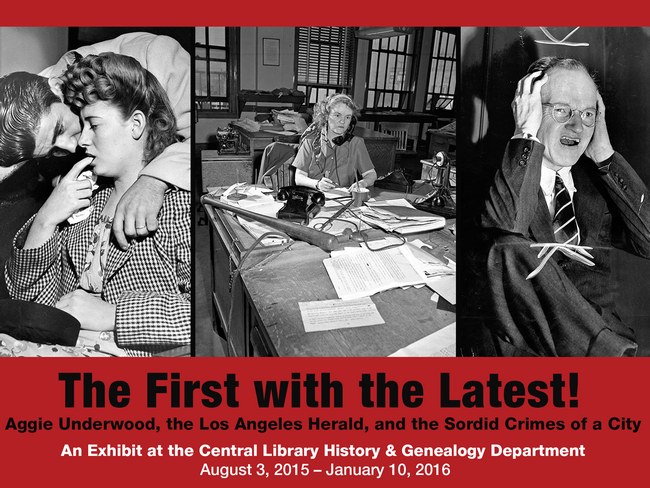

“The First with the Latest! Aggie Underwood, the Los Angeles Herald, and the Sordid Crimes of a City,” explores some of the most deranged L.A. stories that were covered by Agness “Aggie” Underwood, a local reporter who rose through the ranks to become the first woman city editor for a major metropolitan newspaper. Curated by yours truly, Joan Renner (Author/Editrix/Publisher of the Deranged L.A. Crimes website, Board Member of Photo Friends), and featuring photos from the Los Angeles Public Library’s Herald Examiner collection.

“The First with the Latest! Aggie Underwood, the Los Angeles Herald, and the Sordid Crimes of a City,” explores some of the most deranged L.A. stories that were covered by Agness “Aggie” Underwood, a local reporter who rose through the ranks to become the first woman city editor for a major metropolitan newspaper. Curated by yours truly, Joan Renner (Author/Editrix/Publisher of the Deranged L.A. Crimes website, Board Member of Photo Friends), and featuring photos from the Los Angeles Public Library’s Herald Examiner collection.

Join us for light refreshments and brief remarks as we celebrate the reporter who helped the Los Angeles Herald be “The First with the Latest.” An exhibit catalog featuring many never-before-published images from the Herald’s files will be available for purchase.

The reception is on Thursday, August 13, 2015, 6pm-8pm at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles. Christina Rice,Senior Librarian, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection; Stephanie Bluestein, Assistant Professor of Journalism at California State University, Northridge, and I will be making remarks at about 7pm.

I hope to see you there!

Buy the companion book from my Recommendations in the sidebar.

Agness “Aggie” Underwood passed away 29 years ago today. We never met but she has had a profound influence on my life, particularly during the last several years.

I’ve been obsessed with crime novels and true crime since I was a kid, and my compulsion to read it has never diminished. Writing about true crime is a relatively new endeavor for me and I attribute that, in large part, to Aggie’s influence. She is the inspiration for this blog and for the Deranged L.A. Crimes Facebook page, and I am proud to have authored her Wikipedia page — she was long over due for recognition.

As I’ve dug deeper into the crimes that have shocked and, in some ways, defined Los Angeles, I’ve felt Aggie’s presence. Aggie worked in Los Angeles from the late 1920s through the late 1960s — and for nearly two decades she was a reporter. My interest in history and crime set me on the path to write about it, but it’s been my admiration for Aggie that has made me want to tackle many of the same cases that she wrote about.

I gave a lecture at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles on June 29th entitled SLEEPING BEAUTIES: DERANGED L.A. CRIMES FROM THE NOTEBOOK OF AGGIE UNDERWOOD — here is an excerpt from my presentation. I hope you enjoy it.

Thanks for everything, Aggie.

***************************************************

In 1926 as a young wife and mother Aggie had no interest in working outside the home, but she wanted a pair of silk stockings in the worst way. When her husband, Harry, told her that there wasn’t enough money in the budget for her to buy them, Aggie said she’d get a job and earn the money.

Aggie quickly realized that she may have put her foot in her mouth rather than into a new pair of silk stockings; she didn’t have a clue about where to find work. Fate intervened when a friend of hers, who worked at the THE RECORD, phoned and told her that the newspaper needed someone to temporarily operate the switchboard. Aggie took the job and it would turn out to be one of the most important decisions of her life.

Aggie came to enjoy the hustle and bustle of the newsroom and she loved being in the midst of a breaking story. In December 1927, the city was horrified when William Edward Hickman, who called himself “The Fox” murdered and then butchered twelve year old school girl, Marian Parker. Hickman fled after the murder and the resulting manhunt was one of the biggest in the West.

In her autobiography Aggie recalled how she felt when they got the word that Hickman had been captured in Oregon:

“As the bulletins pumped in and the city-side worked furiously at localizing, I couldn’t keep myself in my niche. I committed the unpardonable sin of looking over shoulders of reporters as they wrote. I got under foot. In what I thought was exasperation, Rod Brink, the city editor, said:

‘All right, if you’re so interested, take this dictation.’

I typed the dictation—part of the main running story. I was sunk. I wanted to be a reporter.”

She eventually got her wish and began reporting on stories for THE RECORD. Smart and hardworking, she made a name for herself locally and was courted by William Randolph Hearst for his publishing empire.

She resisted his overtures (and even his offers of more money) because she was happy at THE RECORD. The smaller paper gave her the opportunity to learn all aspects of the business – she thought working for Hearst might pigeon-hole her.

It wasn’t until THE RECORD folded in 1935 that Aggie agreed to become a reporter for THE HERALD. She said that she had heard the term “working for Hearst” uttered contemptuously; but she had been too busy learning her craft to pay much attention to the gibes.

She said:

“…I did not feel I stigmatized myself when I accepted the HERALD-EXPRESS offer. The invitation was a life line, and one did not need to be bereft of ideals to tie onto it.”

In her 1949 autobiography, NEWSPAPERWOMAN, Aggie described what it was like to be a reporter on the Herald:

“The Herald-Express is too fast for the sort of reporter who flounders when he is required to produce a new lead on a running story for each upcoming edition “

Aggie never floundered. She had reported from the scenes of disasters like the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, and she’d also covered some of the most heinous crimes committed in the city.

During the 1930s there were several daily papers in Los Angeles and Aggie had to be a fierce competitor. In her autobiography Aggie wrote about the time she beat another reporter to some photos:

“Once, on a rather cheap murder and suicide, Casey Shawhan, then an Examiner reporter, and I were rifling a bureau drawer for pictures—no we weren’t housebreaking—when we grasped a pile of photographs simultaneously. The tug of war was unequal, for Casey had played football at U.S.C. So I kicked him in the shin. He let go of the pictures and, clasping his bruise, danced on his other leg, howling, ‘O-o-h, gahdammit. I’ll get even with you, Underwood. You wait and see.’” I didn’t wait. I was scurrying off to the office with the pictures.”

Aggie thought of herself as a general assignment reporter; however, she gained a reputation as a crime reporter. Good detectives are observers and so are good reporters, which may explain why stories circulated that Aggie had solved crimes.

Aggie interviewing an unknown bad dame at Lincoln Heights Jail. [Photo courtesy of CSUN Special Collections]

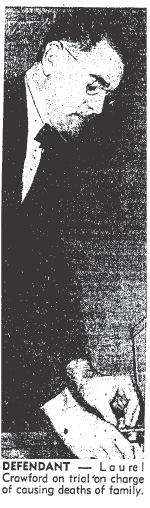

In late 1939, Aggie went out on a story that appeared to be a tragic accident – a family of five had been killed when their car had tumbled hundreds of feet down a mountainside near the Mt. Wilson Observatory. There was one survivor, the husband and father of the victims, Laurel Crawford.

Aggie wasn’t allowed to interview him because cops felt he’d been through enough; however, Aggie made a deal with one of the deputies who allowed her to listen in while Crawford was being questioned. Aggie observed the man, and she had a hunch. One of the Sheriff’s department homicide investigators asked Aggie:

Aggie wasn’t allowed to interview him because cops felt he’d been through enough; however, Aggie made a deal with one of the deputies who allowed her to listen in while Crawford was being questioned. Aggie observed the man, and she had a hunch. One of the Sheriff’s department homicide investigators asked Aggie:

“What do you think of it, Aggie?”

She didn’t hesitate, and replied:

“I think it smells. He’s guilty as hell.”

Aggie had observed not only Crawford’s demeanor, which led her to believe his display of grief was disingenuous, but she had also noticed that his shoes weren’t scuffed, and his clothing wasn’t dirty, torn or wrinkled, which made his story of climbing down the mountain to the wreckage of the family sedan pretty tough to believe. Additionally, Crawford had stated that he had picked up the body of one of his daughters and held her, but there was no evidence of blood on his clothing. Aggie’s Spidey-Sense was engaged.

A thorough investigation of the case proved that Crawford had taken out insurance policies on each of the victims, worth a total of $30,500 (that’s over half a million in today’s money!) Laurel Crawford was sentenced to four consecutive life terms with a recommendation that he never be paroled.

For years Aggie covered everything from celebrity trials to gruesome murders. In January 1947 arguably the most infamous murder case in L.A.’s history broke; the mutilation slaying of twenty-two year old Elizabeth Short.

Underwood was assigned to the story. There have been several people over the years who have claimed credit for naming the victim The Black Dahlia; and Aggie was one of them. Aggie said that the Black Dahlia tag was dug out on a day when everyone was combing blind alleys. She decided to check in with Ray Giese, a Det. Lt. in LAPD homicide, to see if any stray fact may have been overlooked.

According to Aggie, he said: “This is something you might like, Agness. I’ve found out they called her the ‘Black Dahlia’ around that drug store where she hung out down in Long Beach”. Like it? She LOVED it!

Aggie interviewed Robert “Red” Manley, the first serious suspect in the Black Dahlia case, and she was prepared to follow the story to its conclusion when without warning, she was benched.

After a couple of days of cooling her heels in the newsroom she decided to bring in her embroidery hoop. Pretty soon she heard snickers. Aggie said that one of her colleagues laughed out loud and said:

“What do you think of that? Here’s the best reporter on the Herald, on the biggest day of one of the best stories in years—sitting in the office doing fancy work!”

Aggie was quickly reassigned to the Dahlia case, and just as quickly yanked off of it. It was then that she was given the news that she was being promoted to city editor! Aggie said she never understood the timing of her promotion – she would have preferred to follow the Dahlia story until it went cold. But it was an important moment in her career and for women in journalism – Aggie was the first woman in the U.S. to become the City Editor of a major metropolitan newspaper!

*********************************************************************

P.S. I’m currently researching the Laurel Crawford case — it’s diabolical.

Louise Peete’s trial began on April 23, 1945.

Louise had never denied burying Mrs. Margaret Logan’s body in a shallow grave at the deceased woman’s Pacific Palisades home, but she told several colorful stories about how Logan ended up dead in the first place.

As in her first murder trial for the slaying of Jacob Denton over twenty years earlier, Peete claimed to be broke and was assigned a public defender, Ellery Cuff. Cuff had an uphill battle, the evidence against Peete was compelling.

For the most part Louise sat quietly as the prosecution drew deadly parallels between the 1920 murder of Jacob Denton and the 1944 murder of Margaret Logan; however, she disrupted the trial during testimony by police chemist Ray Pinker. From the witness stand Pinker testified to a conversation between Louise and LAPD homicide captain Thad Brown. (In 1947 Thad Brown’s brother, Finis, would be one of the lead detectives in the Black Dahlia case.)

Pinker said that prior to the discovery of Mrs. Logan’s body in a shallow grave in the backyard of her home, Brown had faced Peete and said: “Louise, have you blow your top again and done what you did before?” To which she replied: “Well, my friends told me that I would blow my top again. I want to talk to Gene Biscailuz (L.A. County Sheriff).” Louise spun around in her chair at the defense table and shouted “That is not all of the conversation.” Her attorney quieted her.

Pinker said that prior to the discovery of Mrs. Logan’s body in a shallow grave in the backyard of her home, Brown had faced Peete and said: “Louise, have you blow your top again and done what you did before?” To which she replied: “Well, my friends told me that I would blow my top again. I want to talk to Gene Biscailuz (L.A. County Sheriff).” Louise spun around in her chair at the defense table and shouted “That is not all of the conversation.” Her attorney quieted her.

Pinker testified to how he had found the mound covering Mrs. Logan’s body. He said that he had observed a slight rise in the ground which was framed by flower pots. The cops didn’t have to dig very deep before uncovering Margaret Logan’s remains. When Louise was asked to face the grave she turned away and hid her face with her handbag.

All of Pinker’s testimony was extremely damaging to Peete’s case. In particular he said he tested a gun found Mrs. Peete’s berdroom, and when he tested the bullets they were consistent with the .32 caliber round found lodged beneath the plaster in the living room of the Logan home.

The prosecution’s case was going to be difficult to refute. It must have been a tough call for the defense when they decided to allow Louise to take the stand. Louise could be volatile and unpredictable.

Louise testified that Mrs. Logan had phoned her to ask if she’d keep house for her while she was working at Douglas Aircraft Company. Louise went on to say that when she arrived at the Logan home she found Margaret badly bruised, allegedly the result of Mr. Logan kicking her in the face.

Mr. Logan would be unable to refute any of Louise’s allegations because he had died, just days before, in the psychiatric hospital where he was undergoing treatment. Logan had been committed to the hospital by Louise, masquerading as his sister!

Mr. Logan would be unable to refute any of Louise’s allegations because he had died, just days before, in the psychiatric hospital where he was undergoing treatment. Logan had been committed to the hospital by Louise, masquerading as his sister!

Logan’s death was a boon for Louise and she took full advantage of it by blaming him for his wife’s death. Louise was asked to recreate her story which had Arthur Logan shooting and battering his wife, but she appeared to be squeamish. When she was shown the murder gun and asked by the judge to pick it up to demonstrate how Arthur Logan had used it to kill his wife, Louise said: “I will not take that gun up in my hand.”

Louise’s attorney tried valiantly to contradict the evidence against his client. Would the jury believe him and acquit her?

In his summation District Attorney Fred N. Howser addressed the jury:

“Mrs. Peete has violated the laws of man and the laws of God. She killed a woman because she coveted her property. Any verdict short of first degree murder would be an affront to the Legislature. If this crime doesn’t justify the death penalty, then acquit her.”

The jury of 11 women and 1 man found Louise Peete guilty of the first degree murder of Margaret Logan. With that verdict came a death sentence.

Judge Harold B. Landreth pronounced the sentence:

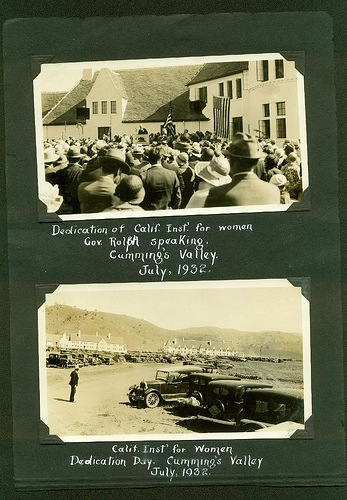

“It is the judgement and sentence of this court for the crime of murder in the first degree of which you, the said Louise Peete, have been convicted by the verdict of the jury, carrying with it the extreme penalty of the law, that you, the said Louise Peete, be delivered by the Sheriff to the superintendent of the California Instution for Women at Tehachapi. There you will be held pending the decision of this case on appeal, whereupon said Louise Peete be delivered to the warden of the State Prison at San Quentin to be by him executed and put to death by the administration of lethal gas in the manner provided by the laws of the State of California.”

It was reported that Louise took her sentence “like a trouper”.

It was reported that Louise took her sentence “like a trouper”.

On June 7, 1945, Louise Peete began her journey from the L.A. County Jail to the women’s prison at Tehachapi to wait out the appeals process.

Louise lost the appeals which may have commuted her death penalty sentence to life in prison. On April 9, 1947 an eleventh hour bid to save her life was made to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court denied the appeal.

Louise would die.

A crush of reporters spent time with Louise on her last night; among them was, of course, Aggie Underwood.

Aggie had interviewed Louise numerous times over the years, and she managed to get at least two exclusives. In her autobiography, NEWSPAPERWOMAN, Aggie devoted a few pages to her interactions with Louise, which I’ll share:

“With other L.A. reporters, I interviewed her there for the last time before she was taken to San Quentin to be executed April 11, 1947.”

“Like other reporters, I suppose I was striving for the one-in-a-million chance: that she would slip, or confess either or both murders, Denton’s in 1920 and Mrs. Logan’s on or about May 29, 1944.’

Louise would not slip; but Aggie gave it her best try. Interestingly, Aggie said that she never addressed Louise as anything but Mrs. Peete. Why? Here is her reasoning:

“I called her Mrs. Peete. A direct attack would not have worked with her; it would have been stupid to try it. She knew the homicide mill and its cogs. She had bucked the best reporters, detectives, and prosecutors as far back as 1920, when, as a comely matron believed to be in her thirties, she had been tagged the ‘enigma woman’ by the Herald.”

“So I observed what she regarded as her dignity. Though I was poised always for an opening, I didn’t swing the conversations to anything so nasty as homicide.”

And in a move that would have occurred only to a woman, Aggie spent one of her days off finding a special eyebrow pencil for Louise:

“…with which she browned her hair, strand by strand. I didn’t go back to jail and hand it to her in person. Discreetly I sent it by messenger, avoiding the inelegance of participating in a utilitarian device to thwart nature which had done her a dirty trick in graying her. Royalty doesn’t carry money in its pockets.”

About Louise, Aggie said: “She wasn’t an artless little gun moll.” No, she wasn’t.

Lofie Louise Preslar Peete was executed in the gas chamber on April 11, 1947– it took about 10 minutes for her to die. She was the second woman to die in California’s gas chamber; two others would follow her.

Peete is interred in the Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles.

NOTE: On March 9, 1950 the DRAGNET radio program aired an episode called THE BIG THANK YOU which was based on Louise Peete’s cases. Enjoy!

http://youtu.be/5ddEOaa4w50

NEXT TIME: Dead Woman Walking continues with the story of the third woman to perish in California’s lethal gas chamber, Barbara Graham.

During the summer of 1933, while Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow were on the lam in the midwest, Los Angeles newlyweds Burmah White, a nineteen year old hairdresser and her husband twenty-eight year old Thomas, an ex-con, were also on the run.

Most newlyweds don’t spend their honeymoon on a crime spree, but Burmah and Thomas were not most newlyweds.

The lovebirds perpetrated ten stick-ups – seven in a single evening (netting them about $220); but the worst of their crimes was the shooting of a popular elementary school teacher, Cora Withington, and a former publisher, Crombie Allen.

Crombie was teaching Cora how to drive his new car. They were stopped at a light when a car driven by a young blonde woman pulled up alongside them, and a man brandishing a gun jumped out of the vehicle. The bandit pointed his weapon at Cora’s head and said: “Shell out, sweetheart; and that goes for you, too, bo.” Just as Cora and Crombie were handing over their valuables there was an explosion – it was a gunshot – and it tore through Miss Withington’s left eye, came out near the right eye and ripped a hole in Allen’s neck. Despite his injury, Allen memorized the license plate number of the bandit’s car!

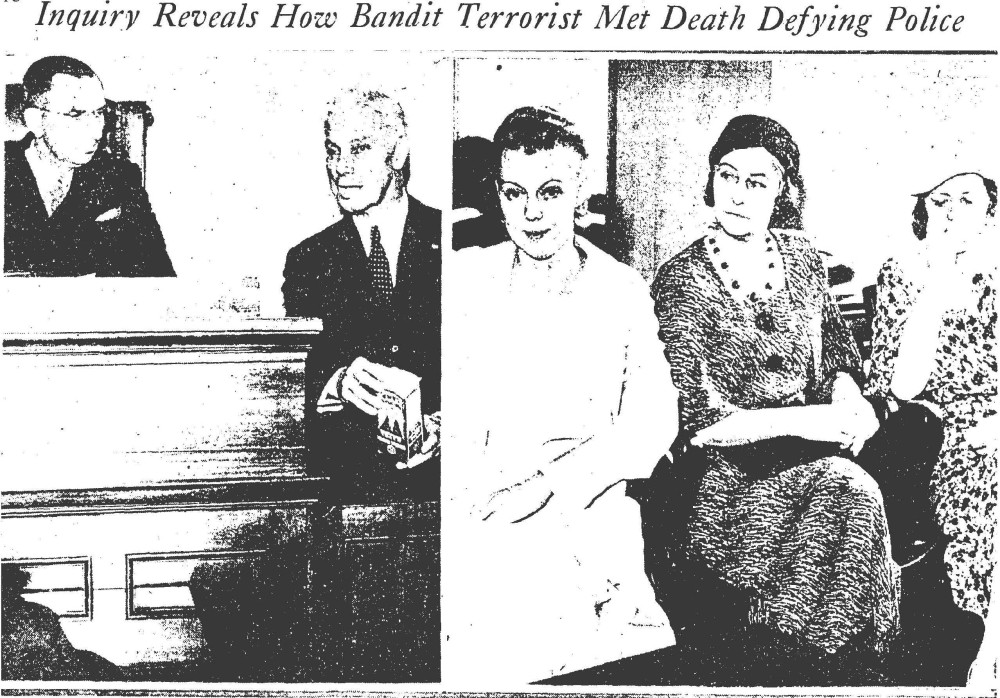

Left: Crombie Allen, retired publisher (right) testifying before Deputy Coroner Montfort at the inquest. Allen identified White as the man who robbed him and Miss Cora Withington, shooting the latter. He could not identify Mrs. White. Right–Mrs. Burmah White, widow of the dead bandit; Policewoman Lula Lane, and Mrs. Violet Dillon, sister of the dead man, at the inquest.

Both victims would survive their gunshot wounds, but the schoolteacher would be permanently blinded.

Chief of Police James Davis immediately instituted a blockade in an attempt to snare the bandits.

The blockade consisted of random stops and searches of pedestrians and vehicles, particularly during the wee hours of the morning when, according to Davis, “the more callous criminals are abroad.”

Chief “Two Gun” Davis wasn’t a big fan of the 4th Amendment. He’d said that constitutional rights were of “no benefit to anybody but crooks and criminals.”

Davis would use a similar blockade strategy later, in 1936, in an attempt to stem the tide of Dust Bowl refugees from Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Whatever his shortcomings, Davis wasn’t wrong about callous criminals working in the city – they appeared to be everywhere. Masked robbers broke into the home of a cop and robbed him at gunpoint; while across town a woman in her 50s held up a rooming house manager who was showing her an apartment.

While the LAPD continued to hunt the Whites, teachers and parents at the Third Street School established a fund to aid Cora Withington, who would not be able to return to teaching because of her injuries.

Things would end badly for the newlyweds.

The cops located their car in a parking lot adjacent to an apartment at 236 S. Coronado Street. An officer dressed in a mechanic’s uniform staked out the vehicle and watched as Burmah got into it and drove it into a garage while her husband held the door open for her. Two officers entered the hallway of the apartment and confronted Thomas White, who made the mistake of attempting to shoot it out rather than surrender. He died after taking two bullets through his heart.

While Thomas White was dropping to the floor dead, Burmah was on another floor attempting either to commit suicide or escape by hurling herself out of a window. Police grabbed her before she could jump and took her to jail.

Burmah’s lack of remorse and abrasive demeanor earned the nineteen year old widow a guilty conviction on eleven felony counts and she was sentenced to a term of from 30 years to life.

At her sentencing Judge Bowron said that Burmah had been “an accomplice in the heartless and wanton shooting of Miss Withington and Crombie Allen”, and that her deliberate intent demonstrated how “utterly abandoned and ruthless she is despite her years”.

Burmah began serving her time at San Quentin, but was ultimately transferred to the Women’s Prison at Tehachapi. Herald-Express reporter, Agness “Aggie” Underwood, interviewed Burmah in prison and described her as “slightly defiant, cynical, and egotistical”. A few years in Tehachapi would mellow Burmah considerably.

Burmah was denied parole a few times before she was discharged on December 1, 1941, just days before the attack on Pearl Harbor. She’d served less than eight years for her part in the 1933 crime spree. Upon her release, Burmah vanished from public view.

NEXT TIME: A Hollywood love triangle ends in death.

Smart and hardworking, Aggie began to earn a reputation as one of the best reporters in town and she was eventually courted by William Randolph Hearst for his publishing empire. She resisted his overtures (and even his offers of more money) because she was happy at the Los Angeles Record. Aggie said in her autobiography, Newspaperwoman, that she had heard the term “working for Hearst” uttered contemptuously; but she was too busy learning her craft to pay much attention to the gibes.

Exterior view of the Herald-Express Building, that was formerly known as the Evening Herald. It was designed by architect Julia Morgan and built in 1925; it is a California Mediterranean style with Churrigueresque detailing. The Herald-Express Building is located on Georgia Street, between 12th and Pico streets. Photo date: November 8, 1937.

Photo and description are courtesy of LAPL.

It wasn’t until the Record was sold to Illustrated Daily News in January 1935 that Aggie agreed to become a reporter for the Herald-Express. Even though she’d been assured of a raise, and told that her place at the Record was secure, Aggie decided to accept a position at the Herald. About working for William Randolph Hearst, Aggie said: “…I did not feel I stigmatized myself when I accepted the Herald-Express offer. The invitation was a life line, and one did not need to be bereft of ideals to tie onto it.”

Now all she needed was a story.