Captain William Bright and the homicide squad understood the importance of circumstantial evidence in winning a conviction in a murder case. They met with Assistant District Attorney Jordan and for hours they reviewed everything that they had assembled in the case against Dr. Frank Westlake.

Captain William Bright and the homicide squad understood the importance of circumstantial evidence in winning a conviction in a murder case. They met with Assistant District Attorney Jordan and for hours they reviewed everything that they had assembled in the case against Dr. Frank Westlake.

The foundation of the case against the doctor was greed. He had in his possession deeds of trust for several lots, bank books and cash belonging to Laura Sutton. He was the beneficiary of a life insurance policy she had taken out and he had even given some of Laura’s personal belongings away–hardly the actions of a man who thought she’d be home soon.

The evidence implicating Dr. Westlake in Laura’s murder was circumstantial, but when taken together it offered a compelling argument for murder committed for personal gain–particularly when her clothing, silverware, and other personal effects were discovered by deputies concealed under the floor and in the attic of his home. They found a typewriter hidden under a pile of clothing too. It was the possibly the same typewriter that had been used to write the so-called “birdie letters”. The letters were purportedly sent by Laura to Westlake inquiring about her pet canaries and some of her other belongings.

One of the letters read:

My dear:

What did you do with the furniture and the birdies? If stored, where? Is Mr. King still in town, and what shift is he working? Please answer these questions in any of the personal columns. Will see you soon.L.B.S.

An inquest conducted by Coroner Nance was held on June 13, 1929. The primary reason for the proceeding was to get on the record the identification of the torso as Mrs. Sutton’s so that the murder trial could go forward. There was no doubt in any of the investigators or scientists minds that the torso and head belonged to Laura.

An inquest conducted by Coroner Nance was held on June 13, 1929. The primary reason for the proceeding was to get on the record the identification of the torso as Mrs. Sutton’s so that the murder trial could go forward. There was no doubt in any of the investigators or scientists minds that the torso and head belonged to Laura.

The sensational murder trial of Dr. Westlake was scheduled to begin on August 19, 1929; however, Westlake’s legal team was wrapping up another case so the trial was continued until August 26th. The case against the doctor was simple. The State alleged that he had murdered Sutton so he could gain control of her assets, and then he mutilated her corpse to cover up the crime.

Nine women and three men were selected to pass judgement on the 57-year-old retired physician. The 8-year-old boy who had found the torso was a witness, as was the 14-year-old boy who had discovered the head. Due to the condition of the body (still armless and legless) the testimony was necessarily scientific. The jury was schooled in the rudiments of forensic odontology so they could understand the dentist’s testimony. Further, bones from the torso were entered into evidence so Dr. Wagner, the autopsy surgeon, could explain how it was possible to determine the age of the victim by the ossification of her bones.

The defense advanced a theory that Ben King had committed the murder because he had once worked as a butcher and knew how to dismember a body. But they seemed to feel that their strongest defense was simply to deny that the torso and head were Laura’s and that she was still alive but in hiding. When his attorney, William T. Kendrick, Jr. asked him if he had killed Laura B. Sutton, Westlake replied: “No, I certainly did not.”

Thirty-six hours after beginning their deliberation the jury returned a verdict of guilty and fixed Dr. Westlake’s sentence at life in prison. One of the jurors said that they’d have brought in a guilty verdict on the first ballot if not for one of the women members who declared that she was a psychologist and from her observations deduced that Westlake was probably not the killer. Apparently she regained her senses.

Sheriff Traeger received a letter from District Attorney Buron Fitts praising the skills of the everyone involved in the torso murder investigation:

The conviction of Dr. Frank P. Westlake for the murder of Laura Sutton, in the so-called torso murder case deserves the highest commendation of this office.

It is with deepest satisfaction that I desire to commend Captain Willikam J. Bright of the homicide department and his able deputies, Allen, Gray, Croushorn and Gompert for their diligent and skillful efforts in marshalling the evidence upon which a conviction was obtained. Their unceasing efforts solving what began to look like a baffling murder, have ultimately been rewarded by a just and conclusive verdict of first-degree murder after a fair and impartial trial.

We are turning over to the family of Mrs. Sutton at the request of Mr. Sutton, the husband, and the brothers and sisters, the body for burial by them, which signifies the satisfaction of the family at the identification of the torso.

Hoping the excellent co-operation between our office and yours will forever continue, I remain sincerely yours,

Buron Fitts

Sheriff Traeger commended his deputies as well:

“…the solution of the torso murder case was a triumph of scientific investigation over old-fashioned methods.”

In this era of DNA evidence we have a tendency to take for granted the skills required to investigate crime outside of the laboratory. Even with the quantum leaps in scientific techniques an investigation is only as good as the men and women who conduct it.

In this era of DNA evidence we have a tendency to take for granted the skills required to investigate crime outside of the laboratory. Even with the quantum leaps in scientific techniques an investigation is only as good as the men and women who conduct it.

What happened to Dr. Westlake? He was paroled on July 12, 1944 after serving only fourteen years in San Quentin for the murder of Laura B. Sutton.

NOTE: Many thanks to my friend Mike Fratatoni for bringing this deranged case to my attention.

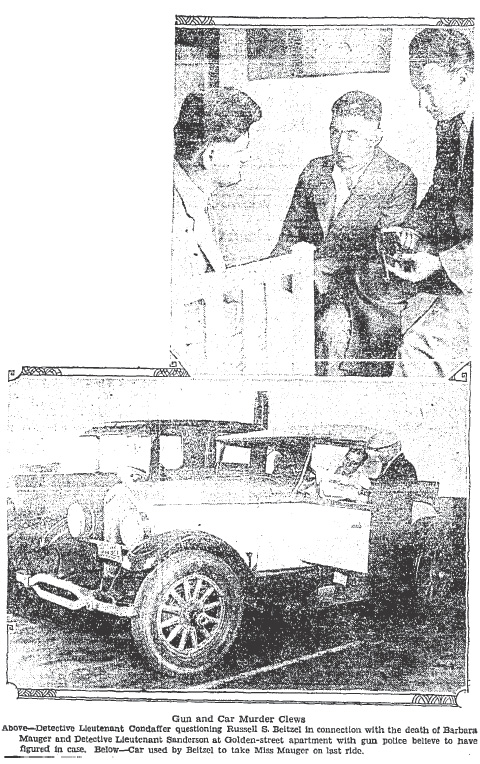

![Convicted murderer, Russell Beitzel getting a shave in prison as other inmates look on, Los Angeles, Calif., 1928. [Photo courtesy of UCLA Digital Collection]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/beitzel-shaved_ucla.jpg)