Before they even had a positive ID on the coyote ravaged body of a woman found on Mulholland Drive police were certain that it was Barbara Mauger, a young waitress who had run away from Philadelphia with her married lover, Russell Beitzel. There was a wedding ring found on the corpse and numbers inside the ring led police to a pawn shop where they confirmed that a woman calling herself Mrs. Burnholme had signed the ticket; and there was a broken string of beads found near the body that matched a necklace known to have been worn by Barbara on the last day she was seen by her neighbors.

Before they even had a positive ID on the coyote ravaged body of a woman found on Mulholland Drive police were certain that it was Barbara Mauger, a young waitress who had run away from Philadelphia with her married lover, Russell Beitzel. There was a wedding ring found on the corpse and numbers inside the ring led police to a pawn shop where they confirmed that a woman calling herself Mrs. Burnholme had signed the ticket; and there was a broken string of beads found near the body that matched a necklace known to have been worn by Barbara on the last day she was seen by her neighbors.

Russell’s denials were having little effect on the cops; he was behaving like a guilty man. He told conflicting stories about Barbara’s whereabouts and he’d given away some of their household items, and had mailed a package of her clothing to a fictitious address in Arizona. Why on Earth would an innocent man do something like that? Beitzel appeared to be on the verge of a move—in fact he seemed to have developed an interest in learning the Spanish and Chinese languages because several books on both were found in his bedroom.

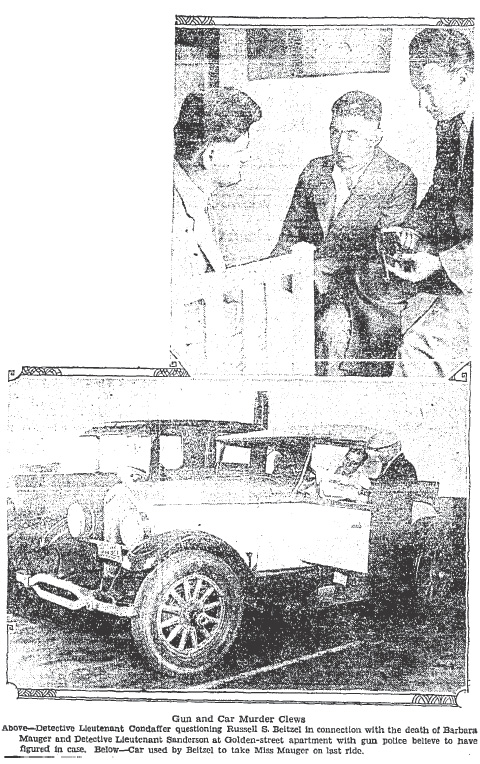

A break in the case came when Rex Welch, the police chemist, tested a hair sample found on some of the Mauger girl’s clothing, the clothing that had been sent to Arizona, and it appeared to be a match for the hair on the body of the young woman in the brush on Mulholland Drive. The chemist was willing to testify that based on the hair analysis the body he had examined was that of Barbara Mauger.

The coroner also issued an appeal to all local dentists to check their files from September 1927 to June 24, 1928 for a record of dental work for Mrs. Barbara Burnholme, the name under which Mauger had been living with Beitzel. The body had three teeth which contained temporary fillings and others that had cavities which indicated further dental work was needed.

The evidence against Russell was stacking up, and LAPD detectives continued to probe their chief suspect with questions regarding Barbara’s whereabouts.

Beitzel stuck to his story that he and Barbara had gone out for a Sunday drive and that they’d had a squabble. He said Barbara got out of the car in a huff and refused to ride home with him so he left her and never looked back. What sort of person drives off and leaves a pregnant woman on a lonely stretch of road at dusk? He could have given her a while to cool off and then returned to fetch her, but he never did; and when the cops questioned him he didn’t seem to be particularly concerned about her welfare.

Investigators located B.T. Redell, the driver of a private rental limousine, who identified Beitzel as the passenger he took to Mulholland Drive on July 1, only one week after the murder; but even when he was confronted with the chauffeur’s story Russell remained a cool customer, he vehemently denied ever meeting Redell and he met every accusation with a denial.

Investigators located B.T. Redell, the driver of a private rental limousine, who identified Beitzel as the passenger he took to Mulholland Drive on July 1, only one week after the murder; but even when he was confronted with the chauffeur’s story Russell remained a cool customer, he vehemently denied ever meeting Redell and he met every accusation with a denial.

For his part, Redell recalled every minute of the ride out to the hills. He said that Beitzel had hired him shortly after noon on July 1st at the intersection of Fifth and Broadway.

According to Redell:

“He (Beitzel) was nervous when he first got the car and told me that he had a cache of liquor in the hills. He said he wanted to check it over.”

On the face of it, it was a plausible story. Prohibition was still in effect in 1928 so the notion that a man might have a few cases of illegal hooch hidden in a remote spot wasn’t enough to make the limo driver bat an eye.

Beitzel directed Redell to a brush covered spot along Mulholland and told him to pull over; then he exited the car then walked away from the road into some underbrush.

Redell said:

“He came hurrying back in about twenty minutes and was more nervous than ever. He told me to drive away as fast as possible and while we were driving he smoked cigarette after cigarette and kept looking back over his shoulder. He said someone had found his liquor and was after him.”

Following the odd drive out to the alleged booze cache, Beitzel directed Redell back to Fifth and Figueroa where he paid the driver $9, and then walked north.

It didn’t seem to matter how many details Redell recalled about his his interaction with Beitzel, the suspect never blinked.

In the long run it wouldn’t matter whether Russell blinked or not because the D.A. was confident that he had enough to successfully prosecute him for Barbara’s murder. In fact the D.A. briefly considered charging him with the death of Barbara’s unborn child, whose tiny bones had been found near its mother, but decided that the additional charge might result in a legal tangle.

The Grand Jury agreed with the D.A. and after hearing only a few witnesses they handed down an indictment for first degree murder—a charge which carried a possible death penalty.

While in jail awaiting trial Russel wrote to Barbara’s father, Henry Mauger, Russell expressed his belief that she was still alive:

“Dear Harry: I don’t know how you feel toward me for what has happened but I know you do not believe I killed Barbara. I loved Barbara too much—too much to hurt her, anyway. I still love her and I do not believe she is dead.”

Beitzel’s letter arrived in the post at almost the same moment as the Mauger’s received a telegram from the LAPD requesting that they come out to identify their daughter’s remains.

Upon their arrival in L.A. the Mauger’s were taken to the place where the body presumed to be Barbara’s was found—the couple wisely refused to look at photos of the woman’s body and of the baby bones found nearby.

Mr. Mauger said:

“Our only hope is that justice will be done. If Beitzel did this awful crime, then he should be punished. If the evidence proves that he did not do it, I still will believe that he was indirectly responsible for her death. If justice is done, that is all I can ask.”

Local wildlife is brutally efficient in reducing the flesh and blood of a human body to bones, and there were so few bits of flesh left clinging to the corpse that the Mauger’s made the identification of their daughter through their knowledge of her dental work and from the general shape and structure of her skull.

Beitzel’s trial began with a fight over whether or not a large photo of the victim’s remains would be displayed in the courtroom—the D.A. won the skirmish and everyone in the courtroom was privy to the revolting photo.

Another black mark against Beitzel was his attorney’s badgering of Barbara’s father over his identification of her remains. Mr. Mauger was visibly shaken during his testimony saying: “This is a terrible ordeal for me.”

After deliberating for less than one hour the jury of five women and seven men returned to the courtroom to deliver their verdict. They found Russell Beitzel guilty of first degree murder and offered no recommendation for leniency, which meant that the convicted man would hang.

Beitzel was sentenced to die on the gallows on November 30, 1928; however, the condemned man appealed his sentence which resulted in a delay while the California Supreme Court decided whether or not to grant a new trial. On April 17, 1929 the Supreme Court denied Beitzel’s appeal and he was re-sentenced to hang—his new date with the gallows was August 2, 1929.

In a desperate eleventh hour attempt to save himself from the noose, Russell Beitzel stated that he had obtained new evidence which suggested that Barbara Mauger was alive and had returned to the east coast. He also contended that the body found in the Hollywood Hills was not that of his former lover. Beitzel’s plea was sufficient to motivate L.A.’s District Attorney, Buron Fitts, to re-examine the case on the slight chance that someone else had murdered Barbara after Russell had left her–or that the body wasn’t hers at all.

According to Beitzel the reason that Barbara was in hiding and would not come forward had to do with pending charges against her for embezzlement for money she had stolen from the Philadelphia department store where she and Russell had been co-workers. Barbara’s father disputed the claim of embezzlement and, in fact, the department store had only filed charges against Beitzel.

Governor Young reviewed the findings in Beitzel’s case and was convinced that the man was guilty of murder and that his execution should go forward.

![Convicted murderer, Russell Beitzel getting a shave in prison as other inmates look on, Los Angeles, Calif., 1928. [Photo courtesy of UCLA Digital Collection]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/beitzel-shaved_ucla.jpg)

Convicted murderer, Russell Beitzel getting a shave in prison as other inmates look on, Los Angeles, Calif., 1928. [Photo courtesy of UCLA Digital Collection]

Described as cheerful, Russell St. Clair Beitzel spent his last hours on death row listening to his phonograph and studying Spanish and ancient history through the University of California extension courses he had been taking. The L.A. Times slyly noted that the condemned man would be unable to complete the advanced courses for which he had recently registered.

As he ascended to the gallows Russell smiled at the crowd of approximately 30 people who had come to watch him die. He joked with the hangman and asked him if he wanted to make “a couple of practice drops” before going through with the actual execution–the hangman declined. A black hood was placed over Beitzel’s head and a rope was tightened around his neck. The trap was sprung at 10:04 a.m. and he was pronounced dead fourteen minutes later.

Among Beitzel’s bequests was a letter to his former death row cell mate, Antone Negra. The letter said.

“Dear Tony–Love and kisses from the next world. It won’t be long now. Had telegram from Polly yesterday. My smile is still with me and can’t be wiped off. My best wishes for your success. Good-by Old Pal.”

In three postscripts Beitzel added:

“Tell the boys hello for me.

“Has Northcott** moved yet?

“Nice place here. Plenty big enough for my handsprings, croquet, fox trotting or spin-the-plate”.

Despite his assertion that his smile couldn’t be wiped off, I’ll bet that when the trap opened up and sucked him into hell his grin was replaced by a tortured grimace.

**Gordon Stewart Northcott was tried and convicted for the torture murders of young boys in the infamous Wineville murder case. The case formed the basis for the 2008 film “The Changeling”. Northcott was hanged at San Quentin on October 2, 1930.