If you missed the webinar on Tuesday, January 26th, please view the recording. It’s a fun trip through fashion, history, and even a little crime.

If you missed the webinar on Tuesday, January 26th, please view the recording. It’s a fun trip through fashion, history, and even a little crime.

Below is the webinar schedule for the remainder of December 2020. Deranged L.A. Crimes webinars will be dark from December 23, 2020 through January 11, 2021.

If you missed the UNSOLVED HOMICIDES OF WOMEN IN LOS ANGELES DURING THE 1940s in November, a brand new version will be offered on January 12, 2021.

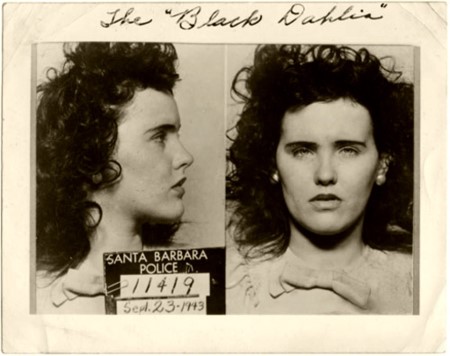

January 2021 marks the 74th anniversary of the murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia. It is fitting that we look at that crime and some of the other unsolved murders of women during that deadly decade.

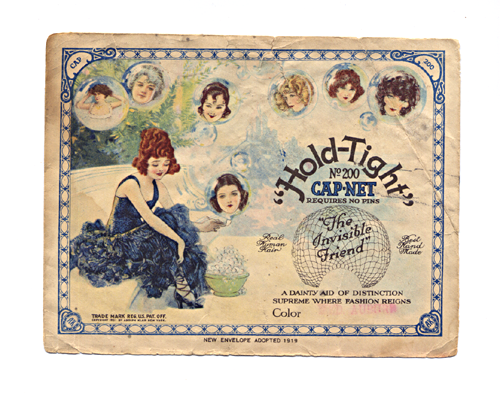

My other passion in life, besides true crime, is vintage cosmetics ephemera, and fashion. On January 19, 2021, the topic is HAIR TODAY, GONE TOMORROW: HOW THE BOB CHANGED HISTORY. You’ll learn about the history of the bob hairdo, a style that has endured for over 100 years. This is my opportunity to display some of the girlie treasures from my vast collection.

Crime topics for 2021 will include: Harvey Glatman: The Glamour Girl Killer and Attic Sex Slave: The Strange Affair of Dolly Oesterreich and Otto Sanhuber.

I look forward to ‘seeing‘ you at the webinars.

In his opening statement in the trial of Paul Wright for double murder, defense attorney Jerry Giesler contended that Wright had no motive for murder until the sight of his wife and best friend in an unmentionable pose turned him into an unreasoning, raging avenger.

Giesler had conceived of a creative defense for his client — he said that Wright’s WWI service, during which he as gassed; a post-war tuberculosis attack, and a voluntary vasectomy combined to make him emotionally unstable, with more violent reactions to shock that normal men.

If the vasectomy defense failed Giesler had a Plan B, and he laid it out for the jury:

“When Wright strolled sleepily into his living room at 4 o’clock that morning, there was absolutely no reason for him to criminally and brutally kill.”

“What he saw there on the piano bench–which he will detail to you from this witness stand…that married man still there at 4 o’clock in the morning beside his beloved wife…that horrible situation was such an emotional shock that it rendered this defendant as unconscious as though he had been hit on top of the head with a tremendous mallet.”

“Under the written law of the State of California–not any so-called unwritten law–it is the plain duty of this jury to acquit Mr. Wright.”

The written law to which Giesler was referring is the crime of passion plea, known as the provocation defense. Historically, according to U.C. Berkeley’s School of Law, California defendants who have used the controversial plea have been able to reduce first and second degree murder charges down to manslaughter. Punishment has often been little or no jail time.

But would the defense strategy work for Wright? The prosecution produced evidence that had Wright sitting on his bed brooding, before arranging a chair in front of a mirror so that he could get a full view of his wife and best friend in a passionate embrace on the piano bench.

Giesler called witnesses to the stand who related a fairy-tale like courtship between Paul and Evelyn, resulting in a blissful marriage — at least for the first couple of years.

In 1936 Paul confided in a close friend that:

“I’m worried to the point of distraction. I’ve earned a fair salary ever since we have been married, but there doesn’t seem to be enough for the household and her demands.”

“I’ve always paid the bills, and it breaks my heart to see my credit go like this.”

I’ve done everything in my power to make her happy–even had myself sterilized, but it seems to be no use.”

The vasectomy had cost Paul one of his most cherished dreams — he’d always wanted a son, and that was never going to be possible for him.

Giesler continued to hammer home the impact of Paul’s “sex sacrfice” which the attorney

contended had destroyed Wright’s self-control when he found Evelyn and John in an intimate pose. Dr. Charles B. Huggins, a Chicago surgeon, described the vasectomy performed on Wright to save Evelyn from the danger of again becoming a mother. She’d nearly lost her life giving birth to Helen and a sterilization operation on her would have been much more dangerous.

From the witness stand, under Giesler’s skilled interrogation, Paul Wright gave his version of the events leading up to the double murder.

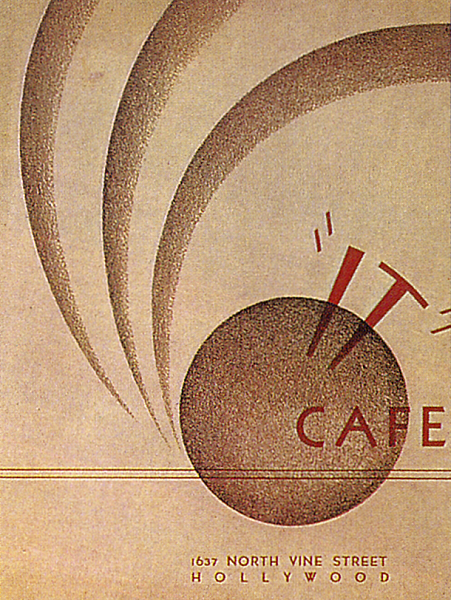

Paul said that he and John had attended a club meeting, then gone out for a nightcap. By 2 a.m. they were at Clara Bow’s “It Cafe” preparing to go home. It was Paul who suggested that John accompany him home, ostensibly to provide back-up when Evelyn questioned him about where, and with whom, he’d spent the evening and early morning hours.

Paul said that he and John had attended a club meeting, then gone out for a nightcap. By 2 a.m. they were at Clara Bow’s “It Cafe” preparing to go home. It was Paul who suggested that John accompany him home, ostensibly to provide back-up when Evelyn questioned him about where, and with whom, he’d spent the evening and early morning hours.

Paul went on to describe feeling fatigued and going to the bedroom for a nap. He told the hushed courtroom:

“I was awakened by some sort of sound–like the piano. It started me up out of my sleep. I went to the living room door and saw that the lights were still on. Johnny was sitting at the piano. I could just see his head. He was looking downward. I couldn’t see Evelyn and I wondered where she was.”

I thought she was on the davenport and I looked, but she was not there. I thought she was in the kitchen. Then I turned–then I turned–I saw Evelyn on the piano bench with Johnny…They embraced and kissed each other.”

“Everything inside me exploded!” he shouted.

“Next thing I knew I was standing there with the gun in my hand. She was on the floor–Johnny was moaning. They were covered with blood.”

It wasn’t possible to know what the jury thought about what they’d heard, but a reporter for the L.A. Times was clear about how Wright had conducted himself: “Seldom in local court annals has a defendant appeared to such good advantage defending himself on the witness stand.”

However the report wasn’t all admiration, Wright was accused of having “robbed his wife’s grave of decency and fidelity” in his attempt to save his own life. And the report went on with: “Johnny Kimmel, by inference was branded a depraved scoundrel by the man who killed him.”

Of course the only people whose opinions mattered were sitting in the jury box.

Wright emotionally and physically collapsed under Deputy D.A. Roll’s blistering cross-examination, and his earlier testimony started to come unraveled. He had maintained that he’d shot blindly at the pair from the bedroom doorway, but changed his story by declaring that when he pumped the final rounds into the two bodies he was standing with his gun in his hand beside the piano.

Wright emotionally and physically collapsed under Deputy D.A. Roll’s blistering cross-examination, and his earlier testimony started to come unraveled. He had maintained that he’d shot blindly at the pair from the bedroom doorway, but changed his story by declaring that when he pumped the final rounds into the two bodies he was standing with his gun in his hand beside the piano.

Also, little details began to surface about exactly what Paul had witnessed that had provoked him to commit double murder. Kimmel was immediately visible on the piano bench, but Evelyn was not.

Deputy D.A. Roll asked Wright:

“Was it in your mind that they had committed some unnatural act?”

To which Wright answered:

“Yes, it must have been.”

At last the prosecution was getting to the the truth of what Wright had seen. Evelyn wasn’t on the piano bench next to Johnny, she was in front of him on her knees! That explains Wright’s violent reaction a little better than what had at first been represented as a kiss and an embrace. From the beginning, Wright’s story made him sound like a Victorian husband who had stumbled upon his wife and a companion in a relatively innocent lip lock — an act which should have merited nothing more than a shout demanding to know what the hell was going on.

Wright also admitted that he didn’t know whether he’d disarranged the clothing of his victims in the manner that they were found later by police!

Sounds to me like Wright had the presence of mind to set the scene of the crime to match his later statements to the cops. How would his conflicting testimony sound to the jury?

NEXT TIME: The verdict and aftermath of Paul Wright’s case.

Clara Bow’s former secretary Daisy De Voe had attempted to use her insider knowledge of Clara’s private life to extort money from the actress; but the truth was she didn’t know much that was worth reporting. So what if Clara liked to party, that was hardly big news in Hollywood. Clara refused to pay her off.

When Frederic Girnau (the publisher behind the excretory rag The Coast Reporter) and Daisy De Voe put their malicious heads together they concocted a revolting 60 page document called “Clara’s Secret Love-Life as told by Daisy.”

When Frederic Girnau (the publisher behind the excretory rag The Coast Reporter) and Daisy De Voe put their malicious heads together they concocted a revolting 60 page document called “Clara’s Secret Love-Life as told by Daisy.”

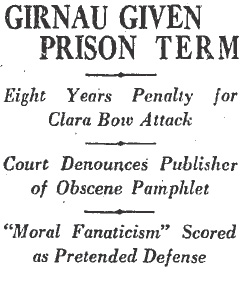

Girnau contacted Rex Bell and offered to sell The Coast Reporter for $25,000 — but Bell, acting on Clara’s behalf, rejected the offer. The spiteful Girnau then sent copies to Will Hays (first president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, and the man for whom the Hollywood censorship code was named), Superior Court Judges, and local PTA officials. By doing so the idiot violated Section 211 of the U.S. Penal Code which prohibited “mailing, transporting or importing anything lewd, lascivious, or obscene.”

Over the years there have been many outrageous stories circulated about Clara Bow. The genesis of the worst of them was Frederic Girnau’s Coast Reporter. The Coast Reporter accused Bow of everything from drug addiction and drunken sex sprees in Mexico to bestiality. It’s no wonder that as soon as she was able Clara left with Rex Bell for his Nevada ranch. Her nerves were shattered.

If Clara had believed that her Hollywood friends would stick by her she was sadly mistaken. There appeared to be few differences between the Hollywood crowd and De Voe and Girnau.

Even though Clara was obviously going through an emotional crisis of Herculean proportions Paramount producer, B.P. Schulberg, didn’t cut her an inch of slack. On the contrary, he bullied her until she relented and agreed to return to the studio for her next picture, “The Secret Call”.

Clara managed to get through the costume fitting and a private rehearsal with director Stuart Walker. But on the day she was supposed to begin shooting at the studio she awoke well before her 6 a.m. call screaming and sobbing hysterically.

Clara’s housekeeper was unable to calm her and phoned Rex Bell for help. When Rex arrived he found Clara still hysterical repeating: “I can’t do it, I can’t do it.”

Rex carried Clara to his car and drove her to the Glendale Sanitarium where she was diagnosed with nervous exhaustion.

Schulberg used Clara’s fragile condition to his advantage. He told her that her health was the studio’s primary concern and that they wouldn’t hold her to her contract if she wanted out. It sounded warm and fuzzy, but It was a disingenuous way of manipulating Clara into saying publicly that she couldn’t fulfill her obligations to Paramount. She told columnist Louella Parsons: “I don’t wanna hold Paramount to no contract”. It was the perfect escape hatch for Schulberg and he took it. He had a release form drafted which relieved the studio of any financial obligation to Clara, and she signed it. Schulberg had saved Paramount $60,000 [equivalent to over $900,000 in current USD].

Clara’s role in “The Secret Call” went to newcomer Peggy Shannon. A former Ziegfeld Girl, and a redhead like Bow, Shannon had been in Hollywood for a very short time when she was spotted by Schulberg who groomed her to be the next “It Girl”. Peggy’s life became another tragic Hollywood story. Her career never really took off and she died of complications from alcoholism in 1941 at age 34. Her husband found her slumped over the kitchen table with a cigarette in one hand and a glass of booze in the other. The poor man was so devastated that he committed suicide shortly after Peggy’s death.

Ironically, B.P. Schulberg’s career didn’t survive much longer than Clara’s. He was pushed out of Paramount, probably due to his liberal politics. He became an independent film producer but Paramount stopped distributing his films in 1937. He produced a few films for Columbia, but retired from the business in 1943.

Clara and Rex were married not long after the trial ended. They had two boys together and they remained married until Rex’s death in 1962. Clara suffered from emotional problems throughout the years and her issues resulted in an estrangement from her family. She spent the last years of her life living in Culver City under the constant care of a nurse.

Clara Bow died of a heart attack on September 27, 1965.

Clara Bow died of a heart attack on September 27, 1965.

What happened to Daisy De Voe and Frederic Girnau?

Frederic Girnau spent forty-two months in a Federal slammer for his poison pen attacks on Clara. Actually, that’s not quite true. The attacks themselves, had they not risen to the level of obscenity, would not likely have caused any problems for the muckraking publisher. However, once they were deemed to be obscene and then sent through the U.S. mail Girnau was in deep trouble. He was released in September 1934, but when he violated his parole by driving drunk he was returned to Leavenworth Prison to finish out his term of 8 years. He died in 1955.

Daisy De Voe (whose real surname was DeBoe) served eighteen months in L.A. County Jail following her conviction for stealing a fur coat from Clara. Daisy wasn’t the only member of her family to have problems obeying the law.

Daisy De Voe (whose real surname was DeBoe) served eighteen months in L.A. County Jail following her conviction for stealing a fur coat from Clara. Daisy wasn’t the only member of her family to have problems obeying the law.

Daisy’s father was arrested in 1931 on a possession of liquor charge (not his first), and her sister Grace was busted in September 1932 after a raid on a still in North Hollywood.

Maybe Daisy matured and reformed because I couldn’t find any trace of her in newspapers after 1933, until she surfaced in her mother’s January 11, 1974 obituary. Daisy had married — her name was Daisy DeBoe Stanek. She’d probably had children too, because her mother was survived by five grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

The harm that Daisy and Girnau had done to Clara was incalculable. But game, set, and match were won by Clara.

DeBoe and Girnau may have enjoyed their fleeting notoriety, but Clara Bow left a legacy of brilliant performances. She has a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, while DeBoe and Girnau are barely footnotes in Hollywood history.

The last words belong to Clara:

“My life in Hollywood contained plenty of uproar. I’m sorry for a lot of it but not awfully sorry. I never did anything to hurt anyone else. I made a place for myself on the screen and you can’t do that by being Mrs. “Louisa May Alcott” Alcott’s idea of a “Little Women”.

Daisy De Voe wanted $125,000 [equivalent to $1.7 million current USD] to keep her mouth shut about Clara Bow’s private life. When her extortion plan failed and she was busted for grand theft De Voe’s attorney, Nathan O. Freedman, used Clara’s private correspondence to humiliate her in open court; and it was all legal. The stolen papers had been submitted as evidence. It was a nightmare for Clara.

Freedman tormented the actress with questions about her relationship with Rex Bell. Clara became angry and frustrated, particularly when he asked her about Daisy’s firing:

“As a matter of fact he (Rex Bell) discharged Miss De Voe from her position as your secretary?”

Clara snapped:

“He didn’t!”

But Freedman continued:

“Well, he’s your secretary now, isn’t he?”

Clara replied:

“He is not; I know it has been printed that he is, but it is not the truth.”

To anyone reading the newspapers it must have appeared that Clara was on trial and not Daisy. Finally, the D.A. questioned Clara about Daisy’s attempt at extortion. Clara testified that only a few days following Daisy’s dismissal W.I. Gilbert, Clara’s attorney, had come to her and told her that Daisy had paid him a visit. The former secretary had demanded $125,000 or, she said, she would turn over certain information she possessed to the newspapers. Then she had the audacity to go to Clara and demand to get her job back!

There was a turning point in the trial though, and it came when a forensic accountant testified that after having double-checked his way through 1,558 of the special account’s canceled checks he discovered a shortfall of $48,000. The special account was the one for which Daisy had access.

Daisy took the witness stand to explain the missing $48,000, but instead she began to tell tales about Clara’s personal life. According to Daisy, Clara played poker six nights a week and had large quantities of liquor delivered to her home on a regular basis. If Daisy was telling nothing but the truth, the jury must have wondered when Clara found the time to appear in films.

Egged on by her attorney’s questions, Daisy told the packed courtroom about Clara’s lifestyle:

“She would rather stay home and play poker than go to the theater or any other place. We played all the time; six nights a week, at least. She never carried any money with her and I had to pay off her debts. Sometimes it was only $4 or $5 and sometimes it was $200.”

The strain of having her life scrutinized in court resulted in Clara absenting herself from the trial. Her physician, Dr. Wesley Hommel, said:

“Miss Bow is suffering from a severe cold and from nervous strain attendant on the trial.” She is running a temperature and I ordered her to bed. Her condition is not serious and she should be up and around in a few days.”

While Clara was ill, Rex Bell, her boyfriend, was a front-seat spectator at the trail.

Nearly three weeks into the trial Judge Doran finally banned the rampant mudslinging, coming primarily from Daisy’s corner. He was interested in having more attention paid to the question of whether she stole Clara Bow’s money than what she knew about Clara’s private life.

It was about damned time.

Clara hadn’t done anything but misjudged Daisy’s character, and yet her reputation had been tarnished. Daisy’s venomous attacks even had a deleterious effect on Clara’s career. The Riverside Board of Censorship barred one of Clara’s films “because of the notoriety” given the actress in the trial of her former secretary. The chair of the board, Mrs. Jessie Joslyn, self-righteously announced:

“Our action in barring the film was taken because of the notoriety given the actress in the Los Angeles trial. Besides, the picture is not of a type we want shown.”

Meanwhile, Daisy’s jury came back deadlocked. They seemed to be confused by one of the judge’s instructions to them regarding “intent to permanently deprive the owner of property”.

Since I can’t time travel, I have no idea why the jury was so confused, or why in the world they found Daisy De Voe guilty on only one of the over thirty counts of grand theft! Even more unfathomable to me was that they recommended leniency for Daisy! They should have thrown the book at her.

Daisy’s request for a new trial was denied, and she was finally sentenced to five years of probation, eighteen months of which she would be required to spend in the County Jail.

Daisy asked for bail so she could be out during the appeal; however, her request was denied a couple of times before she was released on March 28, 1931 on $5000 bail pending an appeal.

Daisy asked for bail so she could be out during the appeal; however, her request was denied a couple of times before she was released on March 28, 1931 on $5000 bail pending an appeal.

While Daisy was fighting her conviction, and Clara was attempting to piece her life back together, a dirt bag named Fred Girnau was taken into custody by the Feds for sending a publication containing alleged obscene articles about Clara through the mails. And where did he get his information? He said he got it from Daisy De Voe.

The misery of having her private life made food for public consumption was finally too much for Clara who, in May 1931, was admited to the Glendale Sanatorium. Paramount studio executives denied that Bow’s illness would terminate her career.

If there was any good news at all it was that Daisy De Voe and H. Girnau were at each other’s throats — suing and countersuing each other over the stories about Clara Bow that appeared in Girnau’s nasty little rag, The Coast Reporter.

Daisy De Voe’s trial caused Clara so much stress that she decided to retire from the film business and live a quiet life out of the public eye. Clara’s contract with Paramount was “terminated by mutual consent” and she moved to Rex Bell’s Nevada ranch.

NEXT TIME: Final thoughts on the “It” Girl and the Secretary.

The indictment returned by the Los Angeles County Grand Jury against Clara Bow’s former secretary, Daisy De Voe, totaled 37 counts of grand theft. Not only was it alleged that De Voe had walked off with some of Bow’s jewelry and personal papers, she was also accused of withdrawing approximately $16,000 [equivalent to $222,434.49 current USD] from one of Clara’s accounts. De Voe was arrested and immediately posted a $1000 bond so she wouldn’t have to await her arraignment from behind bars.

The indictment returned by the Los Angeles County Grand Jury against Clara Bow’s former secretary, Daisy De Voe, totaled 37 counts of grand theft. Not only was it alleged that De Voe had walked off with some of Bow’s jewelry and personal papers, she was also accused of withdrawing approximately $16,000 [equivalent to $222,434.49 current USD] from one of Clara’s accounts. De Voe was arrested and immediately posted a $1000 bond so she wouldn’t have to await her arraignment from behind bars.

De Voe’s attorney, Nathan O. Freedman, filed a complaint on her behalf against Clara Bow, Rex Bell, and three employees of the District Attorney’s office. The complaint asked for $7200 [equivalent to $100,095.52 current USD] damages based on De Voe’s “unlawful detention” for forty-eight hours when she was investigated in connection with missing property said to have belonged to her former employer.

De Voe’s trial began on January 13, 1931, and Daisy’s attorney quickly directed the juror’s attention away from Daisy’s alleged bad behavior by shining a light on Clara’s lifestyle. According to information gleaned from canceled checks, Bow spent over $350,000 [equivalent to $4.8 million current USD] between February 1929 and October 1930 on clothing, automobiles, and going out. Freedman’s diversionary tactics included questioning the actress about payments for whiskey (illegal at the time).

De Voe’s trial began on January 13, 1931, and Daisy’s attorney quickly directed the juror’s attention away from Daisy’s alleged bad behavior by shining a light on Clara’s lifestyle. According to information gleaned from canceled checks, Bow spent over $350,000 [equivalent to $4.8 million current USD] between February 1929 and October 1930 on clothing, automobiles, and going out. Freedman’s diversionary tactics included questioning the actress about payments for whiskey (illegal at the time).

Under cross-examination Freedman asked Clara if she’d authorized a check for $143.50 for whisky and another on March 10, 1930, for $117.50 for whiskey. Clara replied:

“I authorized Miss De Voe to spend whatever was necessary to maintain the household. I trusted her. If she wanted to buy whiskey, why, I suppose, she made out the checks and signed them.”

Freedman continued to question Clara:

“Didn’t you ever look through the books to see what she spent?”

To which Clara replied:

“No, I never looked through the books–that’s why I was so silly–I trusted her.”

Clara was particularly upset when Dep. Dist.-Atty. Clark showed her a canceled check in the amount of $850, and asked asked her if she had knowingly authorized De Voe’s purchase of a fur coat with the money:

“That is my check. I signed it myself. But Miss De Voe brought it to me and said it was to go on my income tax and I signed it because I trusted her.”

Clara broke down in tears when she was asked about an engraved silver dresser set. According to Clara, De Voe had presented the set to her as a birthday gift.

The D.A. asked:

“Did you authorize Miss De Voe to draw a check upon your special account to pay for this set?”

Bow sobbed:

“I never did. I thought she was just being sweet and kind to me, that’s all.”

Clara explained repeatedly under questioning that she had authorized De Voe only to draw checks for her own salary and for household expenses.

At one point Clara leaned forward in the witness box and remarked to De Voe:

“Go ahead and sneer, Daisy, that’s all right.”

Because Daisy had taken many of Clara’s personal papers, including love letters and telegrams, the items were entered into evidence. And of course some of the telegrams, particularly the most personal of them, were read aloud in court. There was a telegram dated September 8, 1930 from Rex Bell to Clara while she was staying at Tahoe, and it read:

“Dearest sweetheart, darling baby, I do miss you, and this is only the beginning. Rex.”

Local newspapers printed as much as they could of Clara’s personal correspondence, which had to have been excruciating for the actress. The papers also printed excerpts from Daisy’s confession to the D.A. — and they spoke volumes about Daisy’s character — or lack thereof.

Daisy had come to L.A. in 1923 after graduating from a St. Louis beauty college. She was employed in two beauty parlors before transferring to the Paramount studio where she eventually met Clara Bow. Clara hired Daisy in 1929.

The former hairdresser had taken every opportunity to defame Clara in her confession. When she was asked about the her duties for the star, Daisy said:

“Well, I did plenty. Her house was terribly dirty. I had the whole place renovated, the drapes taken down and the rugs taken out and cleaned; floors polished; furniture gone over, and everything; and, well, I don’t know what I did.”

In her confession Daisy said that she overheard a conversation between Clara and Rex Bell, in which Bell said he thought Daisy ought to be fired. When she was asked what she did with that information, she said that she decided to go quietly because:

“…Miss Bow was drunk and if I had gotten into any argument with her she would have tried to kill me because she had tried to once before…”

Daisy continued:

“I think it would be better to walk out and later on straighten out her affairs. I wanted to get her things settled as quietly as possible, and keep Clara out of the papers, because one more slam in the papers and Clara is through in pictures.”

Was Daisy really trying to help Clara out of a potentially bad situation? No way. Her confession revealed her attempt to extort money from Clara by threatening to use her personal papers to expose her to public ridicule. For her silence, Daisy told the D.A.’s investigators that she’d asked for $125,000. She said:

“I think it would be to her advantage to keep my mouth shut.”

When she was asked how much money she had drawn out of Clara’s account over and above her salary, Daisy replied that she’d taken $35,000! But in her mind it was all Clara’s fault:

“It was her fault. If she had paid attention to business I wouldn’t have taken a dime from her because she would have known about everything. She wouldn’t even write her own checks. She put me in a position to take everything I wanted. Of course, I didn’t blame her.”

Next Time: The mudslinging continues, and Riverside bans one of Clara Bows films.

By 1930 Clara Bow had been appearing films for eight years, and she’d lit up the screen in every one of them. In 1924 Bow was selected to be a WAMPAS Baby Star.

By 1930 Clara Bow had been appearing films for eight years, and she’d lit up the screen in every one of them. In 1924 Bow was selected to be a WAMPAS Baby Star.

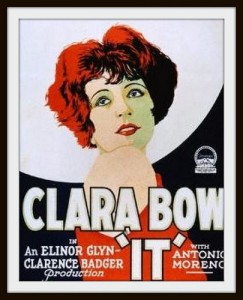

The Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers (WAMPAS), honored thirteen (fourteen in 1932) young women each year whom they believed to be on the threshold of movie stardom. Clara had appeared in about 40 films by the time she made “WINGS” and “IT” in 1927. Both films were financial and critical successes, and Clara was praised as “a joy to behold”. However, she would forever be identified as the “It Girl”.

What is “it”? In his 1904 short story “Mrs. Bathurst”, Rudyard Kipling introduced the concept:

What is “it”? In his 1904 short story “Mrs. Bathurst”, Rudyard Kipling introduced the concept:

“It isn’t beauty, so to speak, nor good talk necessarily. It’s just “It”. Some women will stay in a man’s memory if they once walk down the street.”

In February 1927, Cosmopolitan magazine published a two-part serial story in which Elinor Glyn described “It” as:

“That quality possessed by some which draws all others with its magnetic force. With “it” you win all men if you are a woman and all women if you are a man. “it” can be a quality of the mind as well as a physical attraction.”

There was no question that Clara Bow possessed “It” in spades. The public adored her, and with good reason. Bow had sex appeal infused with enough sweetness and innocence to make her approachable, not saccharin.

There was no question that Clara Bow possessed “It” in spades. The public adored her, and with good reason. Bow had sex appeal infused with enough sweetness and innocence to make her approachable, not saccharin.

Clara was making truckloads of money, and her contemporaries were doing just as well. But many of them were like kids in a candy store, they had no clue about what do with their money except to spend it. Fellow star, Rod La Rocque, became incorporated and his fortune was under the management of a board of directors.

Until about 1928, Clara’s money had been managed by Bogart Rogers. In 1930 her money and her personal affairs were in the hands of her secretary, Daisy De Voe.

On November 10, 1930 local newspapers reported on a story that was eventually going to shine a light on both Clara’s money and Daisy’s management skills. Clara and Daisy had parted ways, and it wasn’t an amicable split.

Both Clara and Daisy denied the stories of the break in their professional relationship. De Voe said:

“As far as I know I am still her secretary. Miss Bow has not served notice on me. I guess I’ll have to find out all about it.”

Clara refused to comment.

A few days later the story got even more interesting when it was revealed that Daisy had indeed been fired by Clara, and then she had helped herself to some of her former employer’s valuables including: diamond jewelry, a sapphire ring, and all of Bow’s insurance papers. In addition, Daisy had also taken a $20,000 cashier’s check, and a mass of personal papers, including canceled checks, paid and unpaid bills, and personal correspondence.

Despite the fact that De Voe had taken thousands of dollars worth of Clara’s belongings, the cheeky amanuensis was gearing up to file a suit against Bow for several thousand dollars that she alleged she was owed for back pay and expenses.

De Voe and Bow had disagreed on what to do with the cashier’s check; but why did De Voe take jewelry and papers belonging to her employer?

“Clara was going to use this in a business deal I had advised her against going into so that is the reason I kept it from her. She knows as well as everybody else that I could never have cashed it. I intended giving it back the same as everything I had that belonged to her. They (the D.A. and cops) treated me terribly and I think it absolutely unjust the way the treated me and kept me at the hotel. I believe, as does my attorney, we have justifiable cause of action against them.”

De Voe intimated that Clara’s latest boyfriend (actor Rex Bell) was responsible for her firing. It is possible that Bell instigated the firing, but once Clara had discovered her belongings were missing she had no other choice.

Daisy’s attorney, Nathan O. Freedman, announced that he was going to file a civil suit on her behalf against Buron Fitts (he D.A.) and Blayney Matthews (a chief investigator for the D.A.’s office). According to De Voe the two had held her incommunicado for several days while they cleaned out her safe deposit box. Fitts didn’t think De Voe had much of a case since the majority of the items found in the safe deposit box had belonged to Clara Bow.

Fitts told reporters:

“This matter came into this office in the nature of a formal request for a criminal complaint against Miss Daisy De Voe for the embezzlement of money and property belonging to Miss Clara Bow. The matter was regularly referred to Mr. Blayney Matthews, chief of the bureau of investigation. After several days of investigation, Mr. Matthews reported back that Miss De Voe had made a thirty page confession of the theft of some $35,000 of Miss Bow’s money, a great deal of which was found in her possession.”

“It is the policy of this office that before issuing a complaint against a private citizen to first thoroughly investigate the case in order to prevent a mistake or miscarriage of justice. This investigation was completed today, and this office has no other alternative under the law but to place the matter before the county grand jury.”

Daisy was quick to deny having made a confession, and she boasted that she had nothing to fear from the grand jury; but she had spoken too soon.

The grand jury indicted Daisy De Voe on thirty-seven counts of grand theft!

NEXT TIME: The De Voe case continues.