Los Angeles County Sheriff’s homicide investigators Det. Sgts. Hamilton and

Lovretovich were following the scarce leads in the case in the “want ad” murder of Andrew Kmiec. The killer had left his bifocals and a couple of unspent .38 caliber cartridges at the scene, but there was no logical place to begin an investigation in a slaying that appeared to have been random. The detectives ruled out robbery — Andy still had $48.43 in his pockets when his body was found.

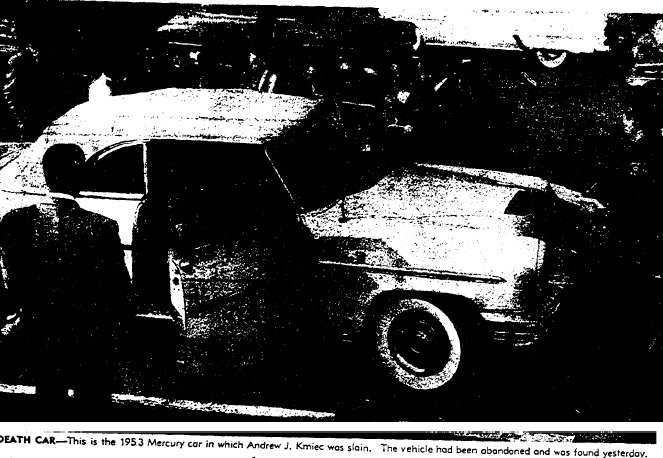

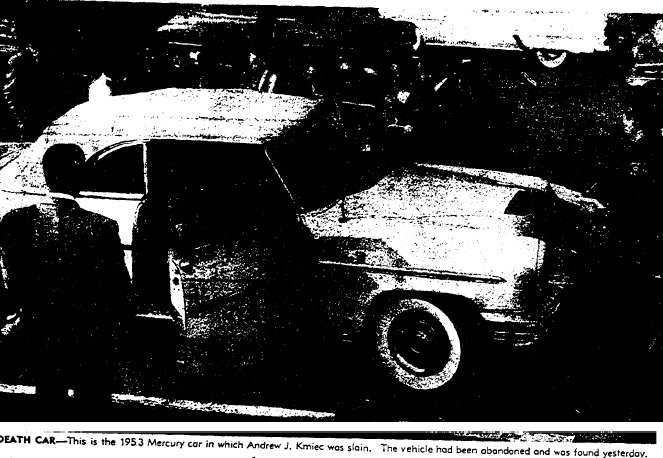

A few days following the slaying detectives received a call from a bartender named Jack London. He’d parked his car at Soto St. and Olympic Blvd. and headed for the cafe where he worked. He thought he saw bloodstains on the lower part of the left door of a Mercury convertible parked next to his car. When he looked inside the car he saw that the seats were smeared with blood. He phoned the cops.

A few days following the slaying detectives received a call from a bartender named Jack London. He’d parked his car at Soto St. and Olympic Blvd. and headed for the cafe where he worked. He thought he saw bloodstains on the lower part of the left door of a Mercury convertible parked next to his car. When he looked inside the car he saw that the seats were smeared with blood. He phoned the cops.

Within minutes the car was identified by police as Kmiec’s. In the rear seat were Dolly McCormick’s coat, handbag, and the Cosmopolitan magazine she’d had with her. Also inside the car was the mate to the lone shoe that had been lying in the road near Andy’s body — the shoe that had first caught the attention of Menlo Butler’s young son.

Actor Kurt Kreuger undoubtedly received a call from the Want Ad Killer — fortunately he didn’t meet him.

There seemed to be no leads forthcoming in the case until Dolly, the only witness to Andy’s murder, began receiving threatening telephone calls at her cousin’s home in North Hollywood. She was advised to keep her mouth shut, or pay the consequences. The cops hoped the calls would provide clues to the killer — but upon investigation they appeared to have been the work of pathetic cranks. Even so, Sheriff’s deputies placed Dolly under a 24-hour guard while virtually every detective in the LASD continued to investigate.

A few citizens reported odd telephone calls they said they had received from an unidentified man after they’d placed a want ad in the newspaper. One of the persons who had likely been contacted by Kmiec’s slayer was actor Kurt Kreuger. Kreguer was attempting to sell his Cadillac El Dorado. A man contacted him and asked him to take the car to the Biltmore Hotel. Kreuger said he would, but first he planned to pick up a friend on the way downtown. At that news Kreuger said his caller seemed to cool, then hedged a bit and said he would call the following day with different arrangements. The prospective buyer never phoned.

Det. Sgts. Lovretovich and Hamilton just couldn’t catch a break — until, out of the blue, Samuel Jones, a Sheriff’s records clerk, spotted something interesting.

So many things in life are a mixture of hard work, intelligence, intuition, and plain old luck. That’s how it was in the hunt for Andrew Kmiec’s killer.

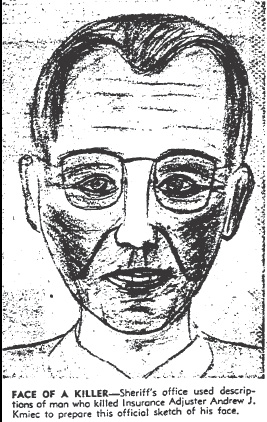

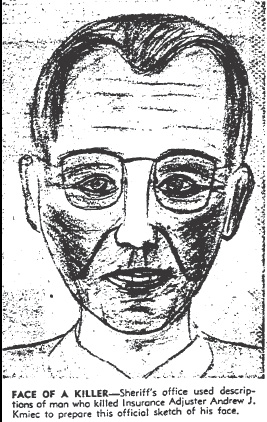

Jones was leafing through a file of police bulletins when he came across the name of Anthony J. Zilbauer, 52, who was wanted for questioning by LAPD’s Hollenbeck Division on a grand theft charge. Zilbauer had stolen furniture from one rental when he and his family had moved to another. Deputy Jones thought that there was a strong resemblance between the police bulletin description of Zilbauer and the description of the want ad killer. So he reported his suspicions to detectives.

Jones was leafing through a file of police bulletins when he came across the name of Anthony J. Zilbauer, 52, who was wanted for questioning by LAPD’s Hollenbeck Division on a grand theft charge. Zilbauer had stolen furniture from one rental when he and his family had moved to another. Deputy Jones thought that there was a strong resemblance between the police bulletin description of Zilbauer and the description of the want ad killer. So he reported his suspicions to detectives.

LASD investigators got Zilbauer’s mug shots from LAPD and showed them to Dolly. Bingo! She immediately ID’d the man as Andy’s killer. Bloody fingerprints found at the scene were matched to those of Zilbauer. The detectives had a suspect and the manhunt was on.

Just a few weeks following Andy’s murder his suspected killer was located in St. Louis, Missouri. With the cooperation of St. Louis law enforcement L.A. Sheriffs laid a trap for Zilbauer. He was captured and arrested when he walked into a post office to pick up a general delivery letter from his wife.

Just a few weeks following Andy’s murder his suspected killer was located in St. Louis, Missouri. With the cooperation of St. Louis law enforcement L.A. Sheriffs laid a trap for Zilbauer. He was captured and arrested when he walked into a post office to pick up a general delivery letter from his wife.

While Zilbauer was being arrested in St. Louis his thirty-four year old bride of two months, Geraldine, was in Los Angeles giving a sworn statement to the district attorney in which she said that her husband had confessed to killing Kmiec. Screw spousal privilege — she didn’t intend to go to prison.

The Sheriff’s investigation had revealed that Anthony Zilbauer was a man of many aliases. He’d picked up the name Bauer when his wife had noticed that there was a pottery company in Los Angeles that spelled Bauer the same way he did. The real pottery company was undoubtedly the inspiration for the phony story he gave Kmiec and McCormick about being in that business.

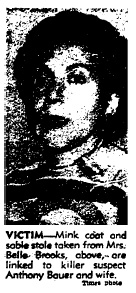

Geraldine had also told the D.A. about a strange overnight trip she and Tony had taken to Las Vegas in November (just a few days after Kmiec’s murder). Geraldine said that her husband had a fur coat, she didn’t know where he’d acquired it, and he wanted to take it to Vegas to pawn or sell it. The couple went to a pawn shop and Tony had Geraldine carry out the transaction on her own. They got $300 for the mink, most of which Tony kept for himself — presumably to finance his flight to St. Louis.

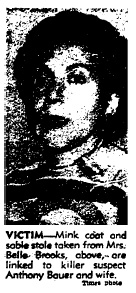

The mink coat that Geraldine and Tony had unloaded in Las Vegas was the property of a woman named Mrs. Belle Brooks. Tony had run the want ad scam on her too. Zilbauer had answered an ad she’d placed to sell her fur coat. When he arrived at her apartment he held her at gunpoint and took the coat and a few of her other personal items.

Hamilton and Lovretovich were sent to St. Louis to collect Zilbauer, who had waived extradition, and return him to Los Angeles where he had a capital murder charge to answer for.

Hamilton and Lovretovich were sent to St. Louis to collect Zilbauer, who had waived extradition, and return him to Los Angeles where he had a capital murder charge to answer for.

Under questioning by D.A. Ernest S. Roll, Anthony Zilbauer confessed to the murder of Andrew Kmiec.

Not surprisingly during his trial Zilbauer attempted to mitigate his responsibility for Kmiec’s slaying by testifying that Andy, who was larger than he by over six inches and at least 60 lbs., had attacked him. One important fact that Tony neglected to acknowledge — Andy may have been larger, but he had a gun.

“The whole thing was a mistake. He brought it on himself–that seems a foolish thing to say–but that’s the way it was.”

Then Zilbauer went on to tell his side of the story which was a pack of lies from beginning to end.

“The last time I saw him was when he was running around the rear of the car. Then I got in and drove away as fast as I could.”

What? Andy probably wasn’t capable of running anywhere after taking rounds to his chest and face. Also there was evidence that his body had been dragged into the ditch where it was later found.

There wasn’t any clear motive in the killing of Andrew Kmiec — the only plausible explanation is that it was a thrill kill — Zilbauer simply wanted to commit murder.

Zilbauer’s wife seemed to think that he’d get only 10 to 15 years for the murder, but Tony was an ex-con, hated prison, and he said he’d rather die.

He stated:

“…they might as well give me the gas chamber as a long prison term.”

Then Zilbauer went on an angry rant about his mother-in-law on whom he blamed everything, um, indirectly.

“If it wasn’t for her, this wouldn’t have happened. She’s responsible, indirectly.”

Tony said that he felt that it was the increased financial burden of having his mother-in-law live with the family that resulted in his crime spree.

On March 4, 1954 it took jurors a mere five hours to find Anthony Zilbauer guilty on count one, the murder of Andrew Kmiec. He was also convicted on count two, robbery and kidnapping with bodily injury in connection with the theft of Belle Brooks’ mink coat and other property.

On March 4, 1954 it took jurors a mere five hours to find Anthony Zilbauer guilty on count one, the murder of Andrew Kmiec. He was also convicted on count two, robbery and kidnapping with bodily injury in connection with the theft of Belle Brooks’ mink coat and other property.

He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for count two, and received death in the gas chamber at San Quentin for count one.

Anthony Zilbauer, a three time loser in Ohio prisons before he came to California, died in California’s gas chamber on May 18, 1955.

NOTE: I’ve covered a few of Det. Sgt. Ned Lovretovich’s cases in the Deranged blog over the past few months. I’ve heard from a friend in the Sheriff’s Department, who has conducted interviews with some of Ned’s contemporaries, that Lovretovich was respected as a detective and thought of as a decent guy. Victim’s families bonded with him, but the people he busted hated him. That makes him a stand-up guy in my book and I know he’s someone I would have enjoyed meeting.

Read some of Ned’s other cases: Thugs With Spoons; Death Doesn’t Sleep; Death of a Free Spirit

![Paul Wright in court. [Photo courtesy of UCLA digital collection.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/paul-wright_ucla-collection.jpg)