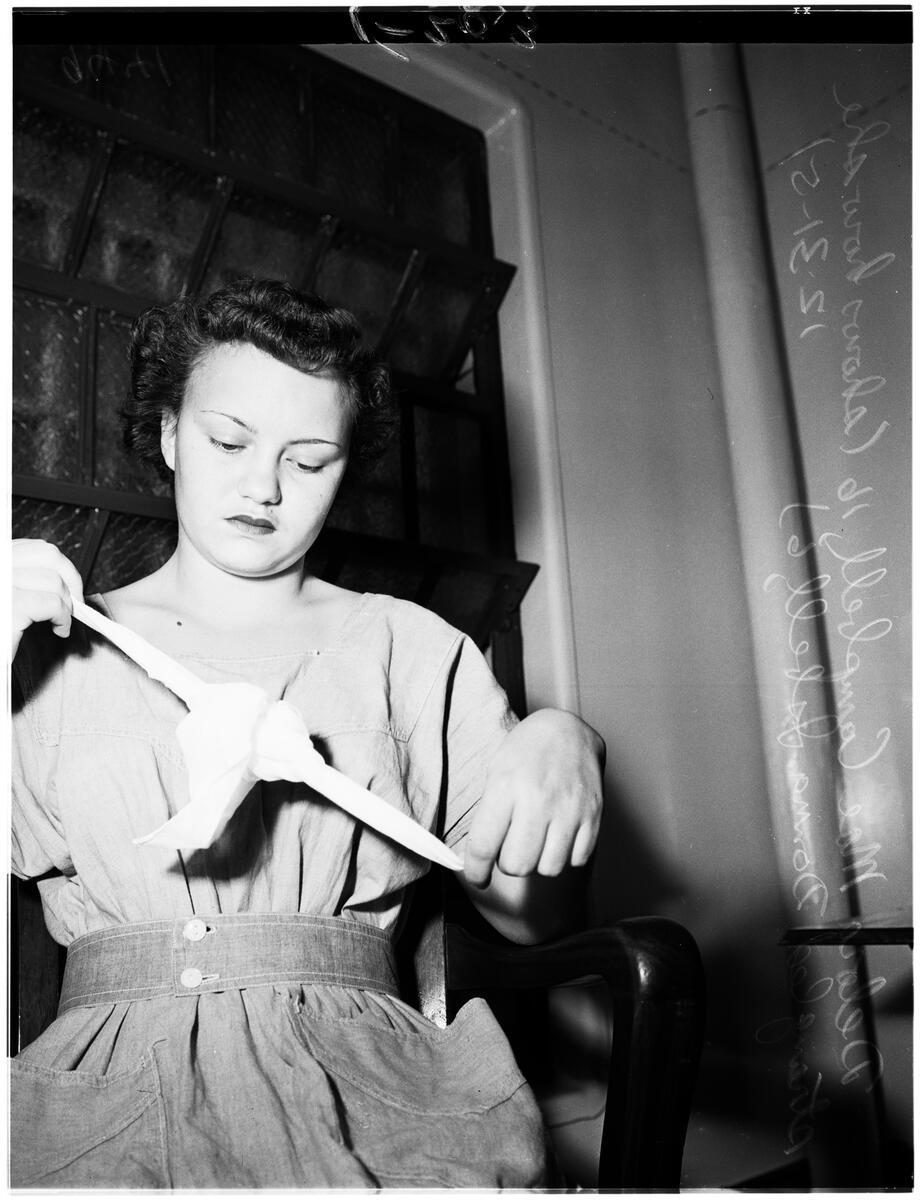

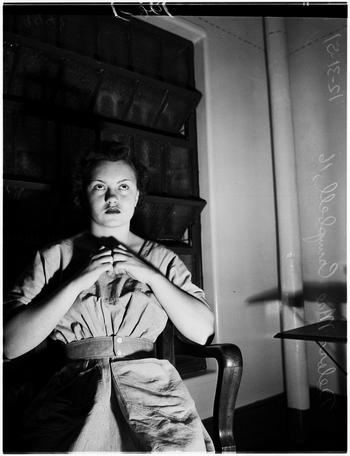

Delora Mae Campbell didn’t cry, tremble, or ask for her parents when accused of strangling six-year-old Donna Isbell. She just stood there.

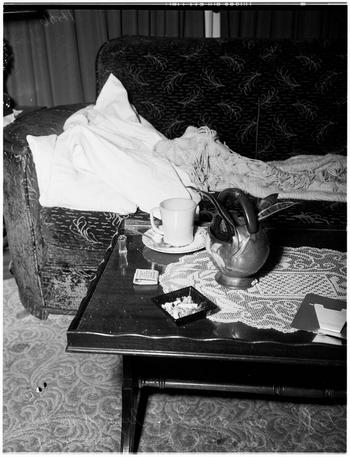

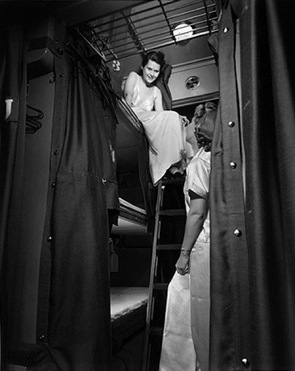

Pending her hearing, authorities held her in isolation in the County Jail rather than Juvenile Hall. Sgt. Frances Cardiff, a jail matron, reported that Delora slept eight hours straight and woke at 5 a.m. on December 31st, quiet and indifferent to both her surroundings and the killing.

When reporters pressed her, Delora couldn’t—or wouldn’t—explain the impulse she claimed had driven her. Maybe it was a vision. Maybe she acted knowingly. “I could have been awake and actually aware of what I was doing,” she said. “I’m not sure.” Asked if she would strangle Donna again, she answered the same way: “I’m not sure.” She said she liked Donna and her older brother, Roy.

What, then, made her do it?

Donna’s parents struggled with their loss, and with a smaller heartbreak of their own. They couldn’t afford the doll Donna wanted so badly for Christmas, but they’d told her Santa would bring it for her February birthday. After the murder, a Marine, Sgt. William Thornton, and his wife, Paula, read about the unfulfilled promise and bought the doll themselves. The Isbells buried it with Donna.

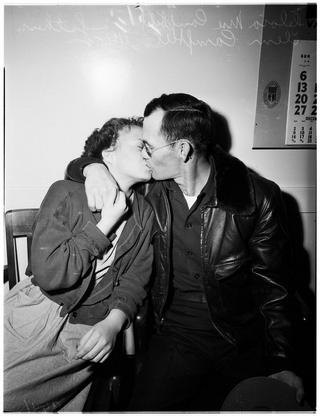

Delora’s father, Clem Campbell, a truck driver from Fort Lupton, Colorado, visited her in County Jail. “We could hardly believe it,” he said. “I guess it was one of those things that just had to happen.” A strange remark from a father whose child had killed another. Not just a strange remark, but a potential window into a family culture of emotional dislocation, which may echo in Delora’s flat affect and her own comment: “I’m not sure.”

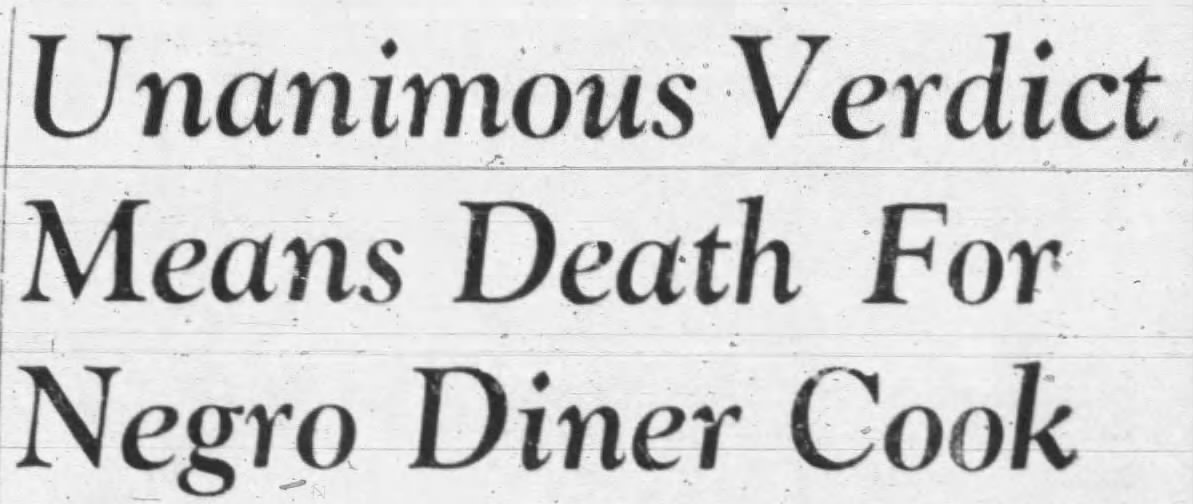

Dr. Marcus Crahan submitted a psychiatric report declaring Delora legally sane. Had he found her insane, she might have avoided adult prosecution; instead, she was nudged toward it.

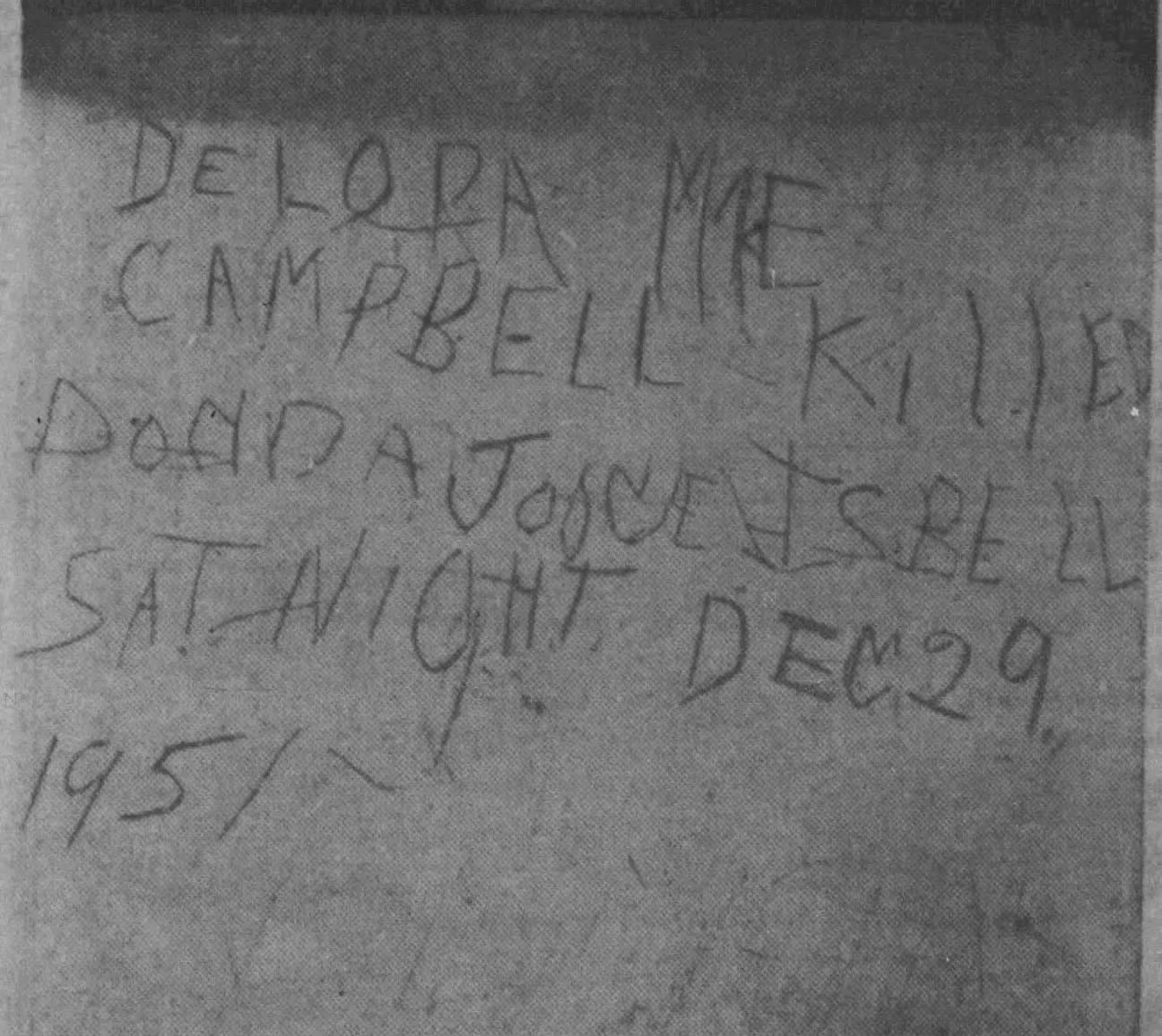

At the coroner’s inquest, Delora took the stand only long enough to say that, on advice of counsel, she would not testify. She didn’t need to. During her isolation, she took a bobby pin and scratched a confession into the enamel of her face-powder compact. No one heard the faint scrape of metal on metal as she wrote:

“DELORA MAE CAMPBELL KILLED DONNA JOYCE ISBELL SATURDAY NIGHT, DEC. 29, 1951.”

Sheriff’s Capt. William Barron asked what prompted her to carve the inscription. “Things got to bothering me a lot,” she said. “I couldn’t talk to anyone, and I felt satisfied about writing—the same as if I talked about it to someone.”

A coroner’s jury found Donna’s death homicidal and Delora probably criminally responsible. The court ordered her to Camarillo State Hospital for a 90-day observation. Afterward, Clem petitioned to have her declared insane and in need of continued care. Two court psychiatrists agreed she was mentally depressed and showed signs of a “disturbed family relationship” and “emotional illness,” but believed she might improve with treatment.

In the early 1950s, psychiatric care for juvenile girls leaned heavily on Freudian interpretation and moral rehabilitation, supported by sedatives and occupational therapy. Whatever treatment Delora received, she followed the rules, and was rewarded with small perks.

Nobody heard anything more about her until April 1954, when she walked away from the hospital. She’d been trusted with grounds privileges for months. With about $70 earned from hospital work, she traveled by bus to Bakersfield, wandered for a few days, then grew tired of “being a fugitive.” She contacted her aunt and uncle in Long Beach—the same relatives she lived with at the time of the murder. They offered to pick her up. When she stepped off the bus at the designated spot, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies were waiting. They returned her to Camarillo.

Sometime in 1956, Delora was quietly released. She returned to Colorado, married twice, had two children, and—so far as anyone can tell—never reoffended. She led a normal life.

Her case leaves behind more questions than answers. No one ever determined what tipped her into violence that December night. In photos, she often appears older than her years—haunted, guarded, carrying something she never named. It’s only an impression, but sometimes an impression is all a case like this leaves.

In the 1940s and 1950s, adolescent girls who committed serious violence often came from chaotic or emotionally barren homes, or from environments marked by humiliation, neglect, or unspoken harm. Whether Delora carried any of that with her is impossible to say. The official record confirms no abuse. It doesn’t rule it out.

Whatever drove her—trauma, dissociation, rage with no safe outlet—remains locked in the silence she maintained after her confession on the compact.

Donna was buried with the doll she longed for. Delora carried only her compact. Between them lies a single moment she called an impulse—irresistible or otherwise—and the truth of it went with her.

NOTE: This narrative draws on newspaper archives, court transcripts, and mid-century psychiatric evaluations. The official record of Delora Campbell is thin, fractured, and filtered through the lens of 1950s ideas about girls, crime, and mental disturbance. I’ve followed the trail where it leads and respected the silences where it stops. In a case built on impulse and uncertainty, the gaps are part of the truth.

Photographs are from the USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection