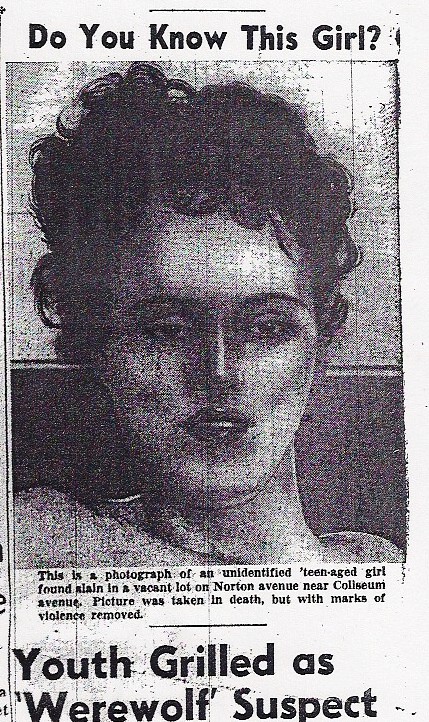

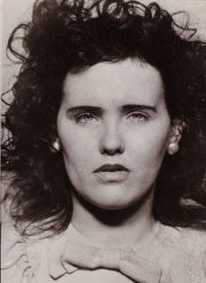

Less than a month after housewife Betty Bersinger discovered Elizabeth Short’s bisected body in a Leimert Park vacant lot, another horror surfaced. On this day, Hugh C. Shelby, a bulldozer operator, found the nude, brutally beaten body of a woman dumped in a field near the Santa Monica Airport.

The Herald rushed out an extra edition:

“WEREWOLF STRIKES AGAIN! KILLS L.A. WOMAN, WRITES B.D. ON BODY.”

Within hours, LAPD identified the victim as 45-year-old Jeanne French.

She had suffered blows to the head from a blunt instrument. But those weren’t the fatal wounds. Her killer stomped on her chest, crushing ribs and inflicting internal injuries that caused her to die slowly from hemorrhage and shock. Heel prints were left on her body.

Mercifully, investigators believed Jeanne was unconscious after the initial head trauma. She likely never saw her killer reach into her purse for her lipstick—never felt the pressure as he scrawled on her lifeless body in crude, angry letters:

“FUCK YOU, B.D.”

“TEX.”

Detectives immediately looked for links between Jeanne’s murder and Elizabeth Short’s. The initials. The mutilation. The proximity in time. But nothing solid connected them. Just another woman dead in the City of Angels.

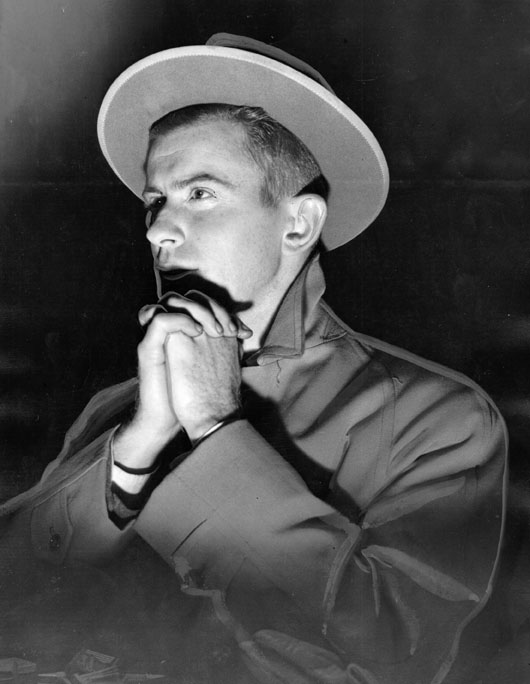

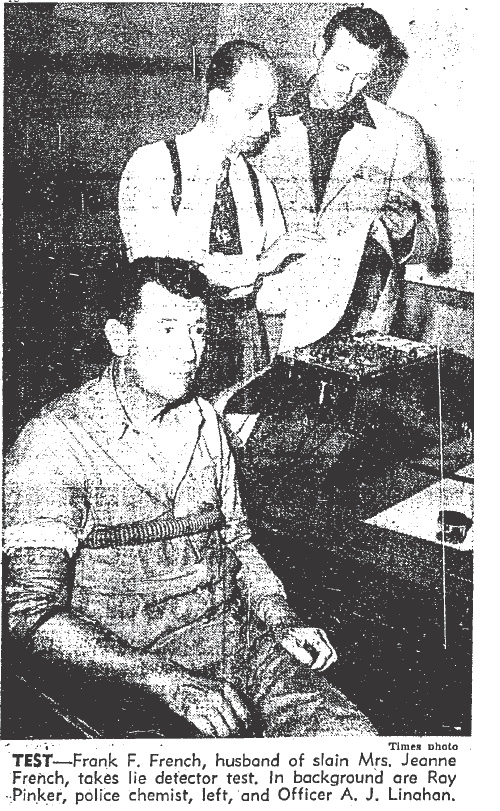

The night before her death, Jeanne visited her estranged husband, Frank, at his apartment. They fought. Frank claimed she was drunk, struck him with her purse, then left. Jeanne’s 25-year-old son, David, was questioned. Upon leaving the station, he confronted Frank:

“I’ve told them the truth. If you’re guilty, there’s a God in heaven who will take care of you.”

Frank replied:

“I swear to God; I didn’t kill her.”

Police arrested him. But his alibi held—his landlady saw him at home during the time of the murder, and his shoe prints didn’t match those on Jeanne’s body. He was released.

Witnesses last saw Jeanne at the Pan American Bar on West Washington Place, sitting at the first stool by the door. The bartender noted she was with a small, dark-complexioned man. They left together at closing.

Her stripped-down 1929 Ford roadster was found parked at the Piccadilly Drive-In at Washington Place and Sepulveda. It had been there since at least 3:15 a.m. A night watchman saw a man leave it there. But Jeanne wasn’t found until hours later. Her time of death was estimated at 6 a.m.—what happened in those three missing hours remains unknown.

Police, ever industrious in the way that gets women nowhere, rounded up the usual suspects—“sex degenerates”—and checked Chinese restaurants after the autopsy revealed Jeanne had eaten Chinese food before she died. None of it led anywhere.

The case, dubbed the Red Lipstick Murder, went cold.

Three years later, amid public outrage and a grand jury probe into the mounting pile of unsolved women’s murders, the D.A. assigned two investigators—Frank Jemison and Walter Morgan—to reopen Jeanne’s case. They worked it for eight months. One painter who had done work for the Frenches and had dated Jeanne emerged as a promising suspect. He wore the same shoe size as the killer and had conveniently burned several pairs. But in the end, he too was cleared.

Like Elizabeth Short, Jeanne French faded into the backlog of cold cases.

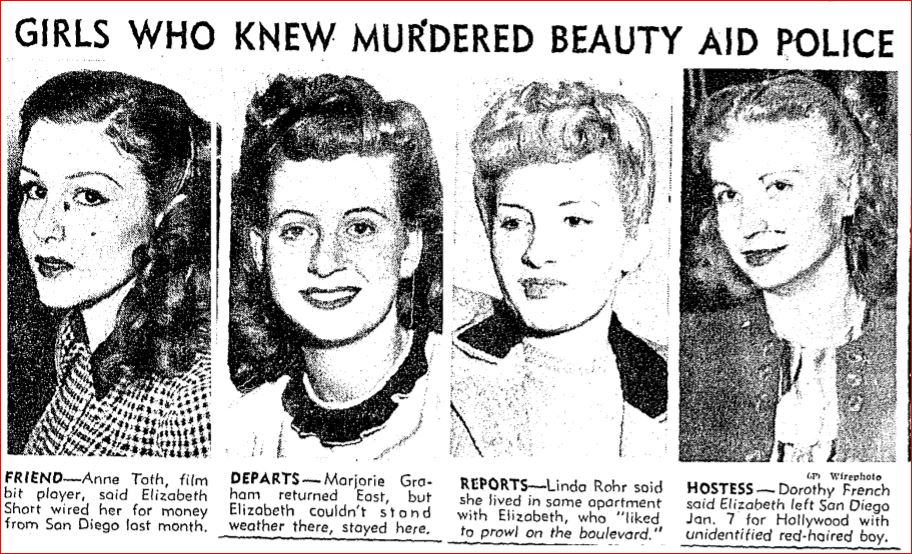

Their names are part of a long list: Elizabeth Murray, Georgette Bauerdorf, Dorothy Montgomery, Laura Trelstad, Rosenda Mondragon, Lillian Dominguez, Gladys Kern, Louise Springer, Jean Spangler, Mimi Boomhower.

Some were murdered. Others vanished without a trace. They became headlines, case numbers, toe tags.

We remember them here—not as victims, but as women who once lived, with hopes and dreams they had every right to pursue.