Ninety years following the undeserved hanging of a young Mexican woman named Juanita for the stabbing death of the Americano who was trying to rape her, another woman named Juanita was sentenced to die. They may have shared a name, but the two Juanitas were polar opposites.

Ninety years following the undeserved hanging of a young Mexican woman named Juanita for the stabbing death of the Americano who was trying to rape her, another woman named Juanita was sentenced to die. They may have shared a name, but the two Juanitas were polar opposites.

Spinelli, known as The Duchess, was the 50-something mother of three, and the leader of a robber gang in Northern California. Her nickname was bestowed upon her by her gang who thought she had a regal air; but to anyone else who had ever met her the nickname had to have seemed ironic because there was nothing royal about Spinelli — neither in her appearance, nor in her actions.

By 1940, Juanita had three children: Lorraine (21), Joseph (17) and Vincent (9). Sure, she had kids, but Spinelli wasn’t anyone’s idea of a warm or loving mother. She had been described as a “scheming, cold, cruel woman” who was the head of an underworld gang, an ex-wrestler and a knife-thrower who could pin a poker chip at 15 paces!

Over the years, Juanita had dragged her kids from the oil fields of Texas, where she’d worked as a waitress and washerwoman, to Salt Lake City where they joined a carnival. Juanita ran a gambling wheel and Lorraine was a snake girl in the sideshow.

Over the years, Juanita had dragged her kids from the oil fields of Texas, where she’d worked as a waitress and washerwoman, to Salt Lake City where they joined a carnival. Juanita ran a gambling wheel and Lorraine was a snake girl in the sideshow.

After they quit the sideshow, Juanita and the kids hitchhiked north and landed in Kilgore, Idaho. Her son Joseph vaguely recollected that while they were in Kilgore his mother met and married a man named Robinson.The family spent a couple of years in Idaho as sheepherders, then the Duchess moved them all (sans Robinson) to Texas. The kids were an inconvenience, so Juanita placed them in a Catholic children’s home and took off for Mexico. When she finally returned Joseph and Lorraine discovered that they had a new half-brother, Vincent.

The Spinelli’s drifted from Texas to Detroit, Michigan. Lorraine had finally had enough and she ran away to California, but the whole family hitchhiked after her! It wasn’t a mother’s love that compelled Juanita to chase after her daughter, the girl was an earner. When Lorraine wasn’t working in a sideshow Juanita was using her to lure new members into the gang. She may, or may not, have stopped short of actually pimping out Lorraine, but in any event it’s no wonder that the girl had taken off.

At some point during her wanderings the Duchess had picked up a common-law Duke, Michael Simeone, who was about 20 years her junior.

In early April 1940, the unholy clan had committed the robbery of a barbecue stand in San Francisco during which the proprietor was shot and killed. What do you do after you’ve committed a robbery and murder? Well, if you’re the Spinelli gang you go on a picnic to discuss plans for more crimes.

On April 14, 1940, while the gang was picnicking on the banks of the Sacramento River, the Duchess decided that one member of the mob, nineteen year old Robert Sherrad, had a big mouth and that he’d been “talking too much” about the fatal robbery to his barroom companions. Fearing that Sherrad would bring heat down on the gang, Juanita ordered her minions to bump off the potential squealer.

Spinelli slipped chloral hydrate into Sherrad’s whiskey and once he was unconscious the kid was driven to the Freeport Bridge in Sacramento and dumped into the river to drown.

The killers had left Sherrad’s clothes neatly folded on the bank of the river so that it would appear that the young man had committed suicide. The cops weren’t fooled and it didn’t take them long to bust the Duchess and her wretched brood.

Juanita Spinelli, Michael Siomeone and Gordon Hawkins were tried and sentenced to death for Sherrad’s murder. Another gang member, Albert Ives, was found “innocent by reason of insanity” and sentenced to an asylum.

Spinelli was reprieved a couple of times but, try as he might, Governor Olson couldn’t find a reason to commute her sentence. Eithel Leta Juanita Spinelli was simply too evil to be allowed to live.

Only Spinelli and Simeone would be put to death; and Juanita has the dubious distinction of being the first woman to be executed in California’s lethal gas chamber.

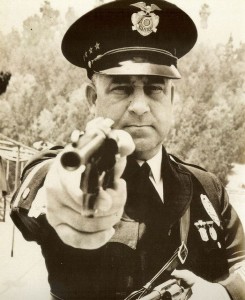

Even San Quentin Warden Clinton Duffy (who was not a death penalty supporter) said of Spinelli: “She was the coldest, hardest character, male or female, that I had ever known, and was utterly lacking in feminine appeal. The Duchess was a hag, as evil as a witch. Horrible to look at, impossible to like, but she was still a woman, and I dreaded the thought of ordering her execution.”

NEXT TIME: Dead Woman Walking continues.

![Juanita Spinella enters San Quentin [Corbis photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/spinelli_corbis-237x300.jpg)

![Coroner Frank Nance at his desk. [LAPL photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/coroner_nance_00042037-300x240.jpg)

![Aggie Underwood interviews mourner at funeral of evangelist Aimee Semple Macpherson. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/00034796-240x300.jpg)

![Hall of Justice, showing Broadway and Temple St. elevations. Old Hall of Justice showing its south elevation is seen in lower right background, behind county jail. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/hojj_1926_00031871-300x235.jpg)