Gun crimes were rampant in Los Angeles during the 1930s, even purse snatchers armed themselves. Robbers, motivated by desperation, hunger or good old-fashioned greed, stalked Spring Street, the “Wall Street of the West”, hoping to pull off the perfect bank heist.

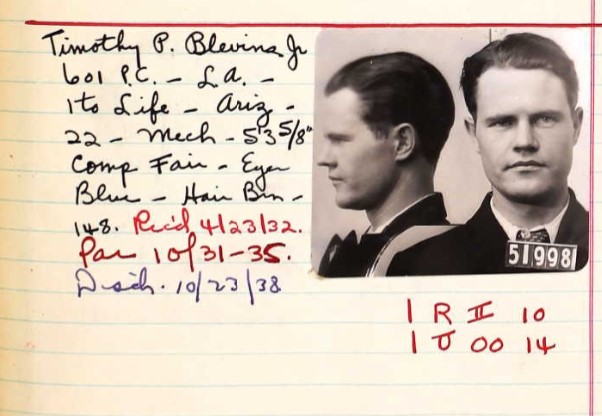

On December 31, 1931, twenty-four-year-old Timothy Blevins found Old Man Depression a formidable adversary. No matter what he did, he couldn’t escape the financial hole he was in. Knowing that he wasn’t alone offered him no consolation. He recently lost his job as a busboy in a cafe at 5610 Hollywood Blvd. He took a job with a county road gang.

Being on a road gang is exhausting work, but he may have stuck with it if his eighteen-year-old wife, Cornelia, hadn’t left him and gone home to her mother. She was just fifteen when the couple had married in Ojai, Arizona a few years earlier, but living with Timothy was no picnic and after three years she’d had enough. He was despondent, and contemplating suicide. Cornelia couldn’t take any more of Timothy’s dark moods, and she intended to get their marriage annulled as soon as possible. It wouldn’t be too difficult for an eighteen-year-old to start over again.

Cornelia bumped in Timothy when she returned to their former home at 1135 South Catalina Street to get some clothing. She was dismayed, but not surprised, to discover that his mood hadn’t lightened. In fact, he appeared to be as morose as ever.

Timothy was sitting alone in the apartment, brooding over how he could change his circumstances—and he devised a plan.

In 1931, the Spring Street financial district, located just north of Fourth Street to just south of Seventh Street, was the beating heart of capitalism in the city. In fact, they referred the area to as the “Wall Street of the West.” There were at least twenty banks concentrated within a few blocks. The eleven-story steel frame building at the corner of Fifth and Spring Street that housed the Security-First Bank stood out. Built in 1906 by the architecture firm of Parkinson and Bergstrom, the Italianate style structure was the tallest building in Los Angeles until 1911.

It was shortly after 2 pm on the last day of 1931, and while the Security-First Bank was no longer the only skyscraper on Spring Street, it was still impressive enough to look to Timothy like an opportunity. He resolved to take it. He gripped his case tighter and stepped over the threshold into the crowded lobby.

Tracy Q. Hall, the vice president of the bank, was in his office and a dozen customers waited to have a word with him. Blevins strode up to the rail which enclosed Hall’s office and placed the case he was carrying on the wood work. He handed Hall a note. The crudely printed note, written on a blank check from the Bank of America, contained a demand for $100,000 and stated that there were enough explosives in the bag to turn the block into smoke and ashes.

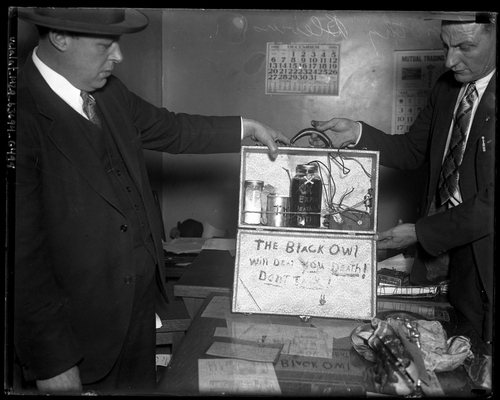

Hall quietly read the note and then glanced up slowly to take the measure of the man who would dare to make such a loathsome threat. Timothy drove his point home and, to reveal the contents of the case; he snapped open the catch and suddenly the “infernal machine” (a bomb) was visible.

The two men continued to hold each other’s gaze, but Timothy blinked first. He released his grasp on the case, whirled around, and ran for the exit. Hall grabbed at the fleeing man but just missed him. Blevins continued to run and, in his haste, he knocked down Peter J. Anderson, a patron of the bank and proprietor of a garage at 221 East Fifth Street.

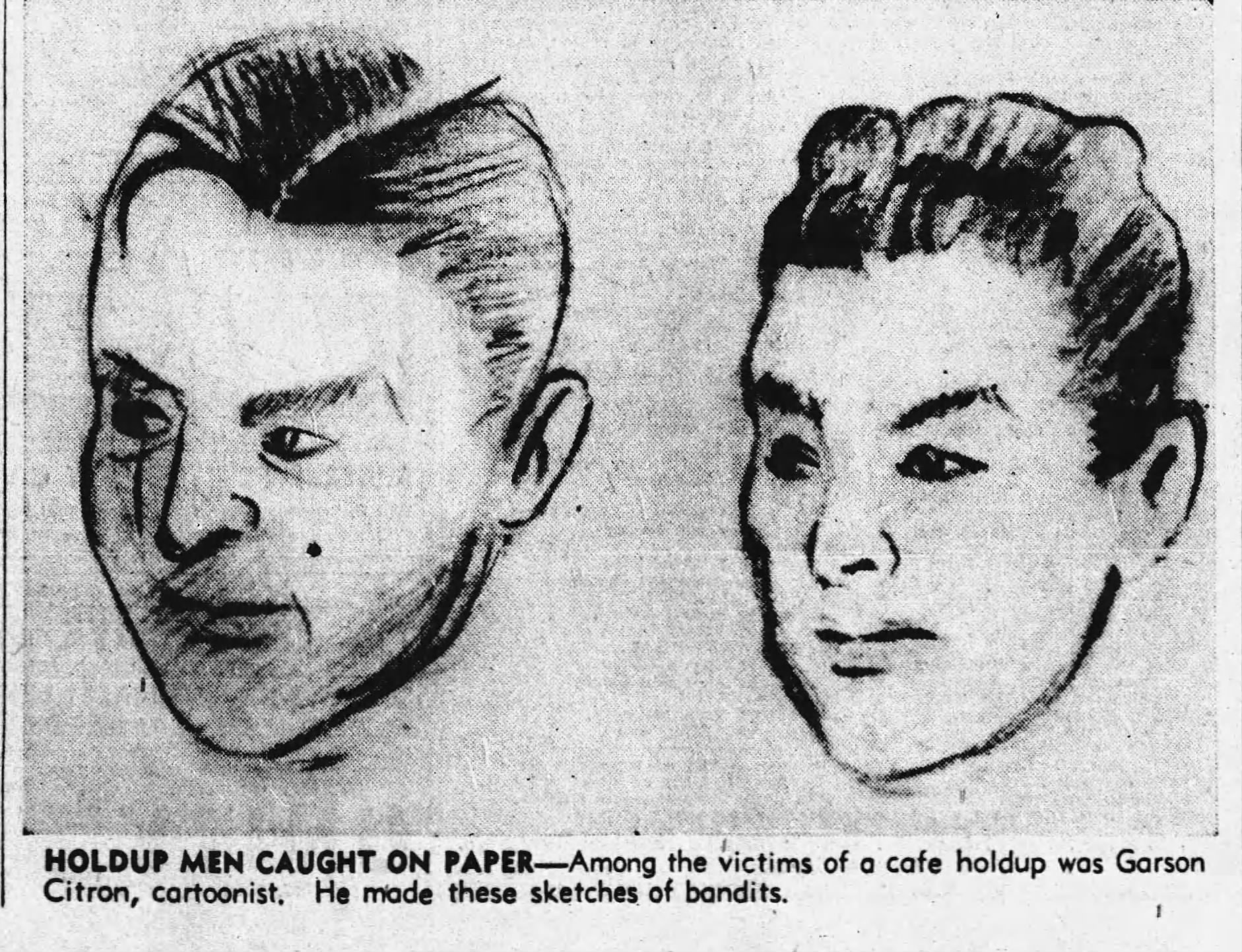

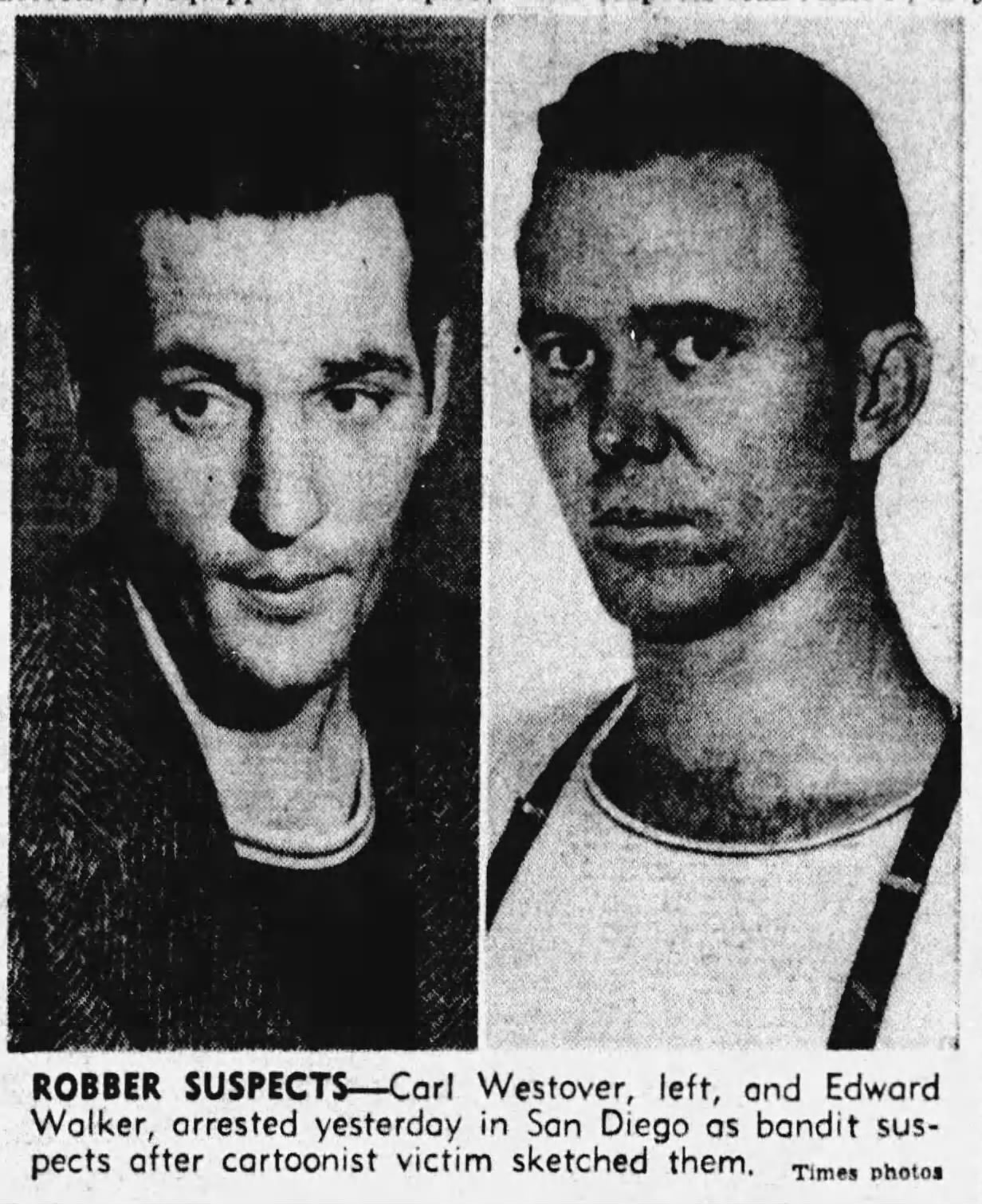

Anderson let out a cry, and so did Hall, who was in hot pursuit of the fleeing man. Timothy dashed out onto Fifth Street and it looked like he was leading a parade. Behind him were Anderson, Hall, and Sam Sulzbacher, the bank’s doorman. When they reached Main Street, Traffic Officer R. W. Olsen joined the chase.

Timothy ducked into a theater on Main, but Officer Olsen has seen him go into the building. Naturally, Timothy tried to blend in with the theater crowd, but it was no use. Olsen found him and took him into custody.

While police escorted Timothy to their headquarters, Hall turned the infernal machine over to LAPD Captains McCaleb and Malina. Upon examination of the device, they found a dry battery wired to a quart jar full of ethyl gasoline. Also, inside the case, there was an empty milk can and a small bottle of carbide powder; above the quart bottle were two brown sticks of dynamite.

On the lid of the box, printed with black paint, was an admonition:

“The Black Owl. Will deal you death. Don’t talk,”

Then McCaleb and Malina read the note that the suspect had handed to Hall:

“There is enough explosive here to tear up the block. Read carefully. Do exactly as told. Starting with biggest denominations fill bag. We will go to the vault first. When I have enough, you will take me out the back door. Get me a taxi. Then take your time going back, or I have to take care of you. If you describe me too well, this will not fail to work. There is poison gas to kill every one (sic) within.”

The note was terrifying, but it wasn’t enough to prevent Tracy Hall from doing his best to bring the robber wanna-be to heel.

At police headquarters Timothy, sullen and mumbling incoherently, refused to make any statement other than to tell the cops: “you can call me Dave Lowre.” Then he attempted to snatch a pistol from Officer Olsen. Half a dozen detectives jumped on him and prevented his escape. He became somewhat more cooperative following his aborted escape attempt, but he never revealed the inspiration for his nom de felon.

The judge arraigned Timothy in Municipal Court and set his bail at $10,000—he was stuck.

The complaint against Timothy charged him with burglary, attempted robbery and violation of Section 601 of the Penal Code because he transported dynamite into a public building, endangering the lives of others.

Timothy originally pleaded insanity, but he withdrew the plea. Instead, he entered a plea of guilty to the charge of illegally transporting dynamite. The likely reason for his change of plea was that he could apply for probation if he wasn’t insane.

Timothy hoped for probation, but the judge denied him, and sentenced him to San Quentin.