August 29, 1951 — 10:30 p.m.

Scrivner’s Chili Dog Stand

East Olympic and South Atlantic

East Los Angeles

Nina Bice, a 25-year-old divorced mother of three toddlers, was drinking coffee with her fiancee, William Hannah at the Scrivner Chili Dog Stand when William heard a loud crack. He assumed it was kids playing with leftover fireworks from the 4th of July, or a car backfiring. He turned toward Nina and found her slumped over, a bullet behind her right ear. She was dead.

Over the next eight months a mysterious shooter, dubbed the Phantom Gunman by newspapers, shot and wounded four women and a girl in a crime spree that terrified locals.

Evan Charles Thomas. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

On April 16, 1952, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies arrested twenty-nine-year-old railroad switchman. He told detectives, “I’m glad it’s over, it’s been bothering me.”

He claimed he didn’t intend to kill Nina. Like a wild west sharpshooter he tried to shoot the coffee cup out of her hands, but he missed. Evan’s pregnant wife Hester went into hiding and filed for divorce. Her father told reporters, “We’re trying to be calm about this. While we’re ashamed, we’re trying to hold our heads high.“ A reported asked if Hester planned to stick by her husband, to which her father replied, “Stick by him? Do you think any reasonable person would?”

With a perverse sense of pride, Evan lead investigators on a tour of his assaults. He told them that after he purchased the .22 rifle he prowled in his car searching for attractive women. He was a coward, inept in social situations, and probably sexually impotent. To gratify his urges, he hid in the shadows and acted out with violence and he found it gave him an erotic charge. Evan masturbated at the scenes of his crimes. He described for investigators how, following an attack, he would circle around in his car and find a vantage point from where he could watch all that his actions had wrought while he pleasured himself.

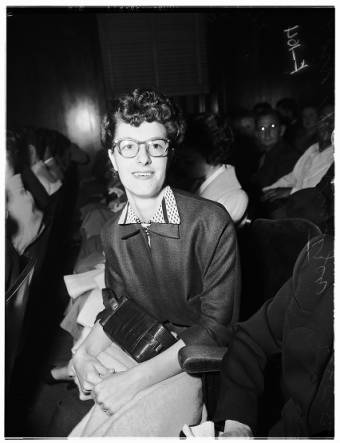

Lois May Kreutzer [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC].

He led sheriffs to the Pico Rivera phone booth where, on August 27, he shot Lois May Kreutzer, 21, in the back while she was called a doctor for her sick child. She was unaware of the cause of her pain and the seriousness of the wound. She believed a bee stung her, and she walked home.

Thomas took deputies to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd Walter in Norwalk, where he shot through the front window on August 28, the night before he shot Nina.

The bizarre tour took detectives to Downey, where on October 16, Patricia Ellen Bryant, 10, suffered a gunshot to her arm (breaking the bone) as she waited for the school bus. Patricia was reading a book in front of her house when the attack occurred. Her dad was furious and threatened to punch Evan if he ever got close enough.

Deputies accompanied Evan to Pico Rivera where, on November 23, he shot Irma Megrdle in her left thigh while she was gardening in her front yard.

In the city of Garvey, Evan took deputies to the spot where he hid himself when he shot Audrey Murdock in the right side while she was ironing. Even though she was in agony, Audrey left the house to seek help. She was in the hospital for ten days and left with the bullet still her. The doctors could not safely remove the slug.

Evan visited the chili dog stand and took detectives to his hiding place in the nearby alley from where he took the fatal shot. As per his routine, he then drove around the block, staked out a prime vantage point, watched the excitement, and masturbated.

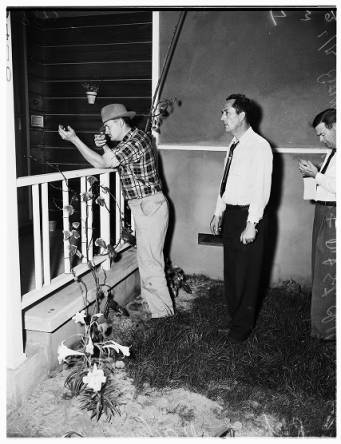

Joan Frances Hilles points to the window where the bullet entered. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

The final stop on Evan’s tour of terror was to the home of his near neighbor Joan Frances Hilles’ home in Los Nietos. Evan recently spent the evening with Joan socializing, drinking beer, and watching TV. Five minutes after he left her, a bullet shattered the living room window and whizzed past Joan’s head.

Evan Charles Thomas demonstrates for Sheriff’s investigators from where he took the shot at Joan Hilles. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

The Hilles’ considered Evan a hick. On the night of the attempt on her life, Joan let him hang out with her because he brought the beer. Soon after firing the shot, Evan called the Hilles’ home to ask if Joan was okay. His called begged the question, how did he find out about the incident so fast?

Unable to control his curiosity, he did one of the dumbest things a perpetrator can do, he visited the scene and pestered investigators with questions. Detectives suspect the person who attempts to insert him or herself into an investigation. Charles was interested to the point of being obnoxious, and it was his intense interest that lead to his arrest. As soon as investigators turned their attention to Thomas, and he confessed to Nina’s murder and confirmed his identity as the Phantom Sniper.

Evan Charles Thomas in court with his attorney, John Oliver. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

During Evan’s trial, County Jail physician Dr. Marcus Crahan offered his professional opinion of Charles. He described him as a low-grade moron who was fired from one job because he couldn’t use a cash register. The Post Office let Evan go after he crashed his mail truck in 1948. Crahan told the court that Evan was a subnormal every man–a guy who watched wrestling on TV, drank too much when he fought with his wife, lusted after other women but was too shy to do anything about it, and argued with his in-laws. Crahan’s description fit thousands of men in the early 1950s; however, the crucial difference between Evan and other men was he focused his frustrations in an anti-social direction.

Psychiatrist Dr. Edwin Ewart McNeil examined Evan and declared him sane. The primary reason for his diagnosis made sense. Charles told him his overwhelming emotion before, during, and after the shootings was abject terror.

Evan Charles Thomas following his conviction for murder. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

The jury found Evan guilty of Nina Bice’s murder and sentenced him to die in the gas chamber. The district attorney set aside six charges of attempted murder. Prosecutors were hedging their bets. In the unlikely event Evan slipped through a legal loophole on Nina’s murder, he had multiple charges waiting to be filed.

Death penalty cases are automatically entitled to an appeal. Evan’s appeal revealed a jury made up of other subnormals. The defense attorneys based the appeal on the jurors’ inability to grasp the concept of lying in wait. The jurors actually believed a killer had to be prone on the ground when he fired. The court denied the appeal.

The original Phantom Gunman was on death row, but a copycat popped up in July 1952 when several women were shot and wounded in the San Gabriel.

Evan Charles Thomas on his way to San Quentin to be executed for murder. [Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection, 1920-1961, USC]

January 29, 1954. The State of California executed Evan Charles Thomas in the gas chamber at San Quentin for Nina Bice’s murder. His mother, in Akron, Ohio, told the press she blamed the Air Force for her son’s problems. She said, “They teach them how to use a gun, and when they get out and get into trouble, they do nothing to help.”

In a dreadful postscript, in September 1955, Nina Bice’s ex-husband Emory Bice, the father of her three children, was crossing a street in East Los Angeles when he was hit by a hit-and-run driver and killed. He left a young widow, Kathleen, to care for his three kids with Nina, and their two children together.

NOTE: Thanks to Robert Harrison, a Deranged L.A. Crimes reader, who reminded me about this story.

The holidays are a time for family, and Sarah Marquez and her two-year-old son, Eric, were looking forward to Christmas 1953 with more enthusiasm than ever. Eric was too young to recall his parents ever living together, they separated when he was an infant, but if all went well on December 18th, the family would be reunited.

The holidays are a time for family, and Sarah Marquez and her two-year-old son, Eric, were looking forward to Christmas 1953 with more enthusiasm than ever. Eric was too young to recall his parents ever living together, they separated when he was an infant, but if all went well on December 18th, the family would be reunited.

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene.

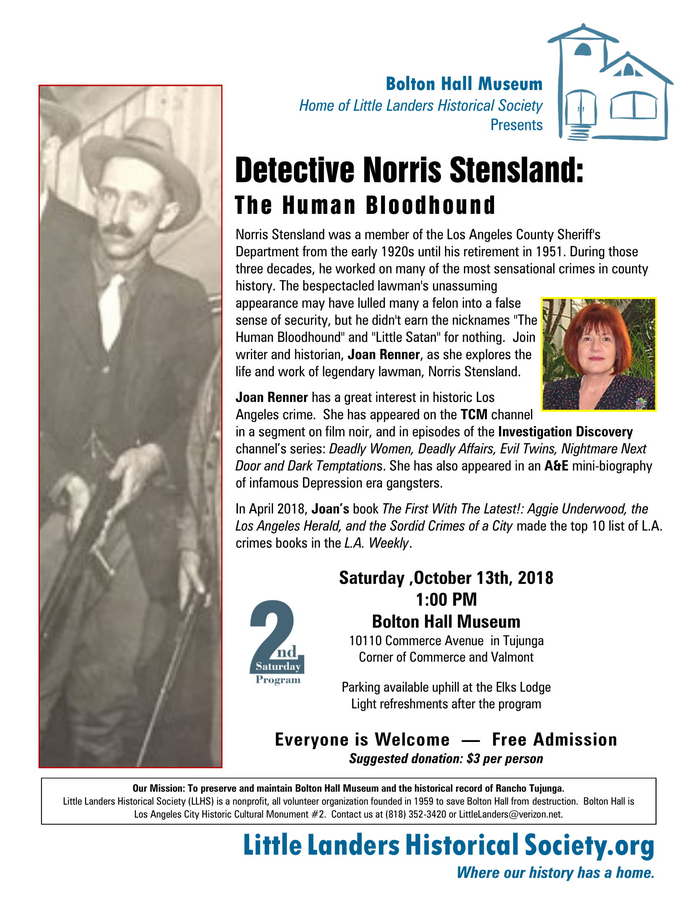

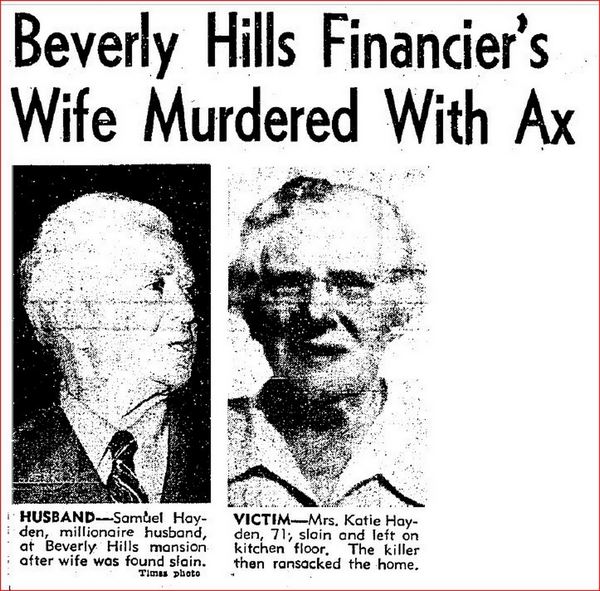

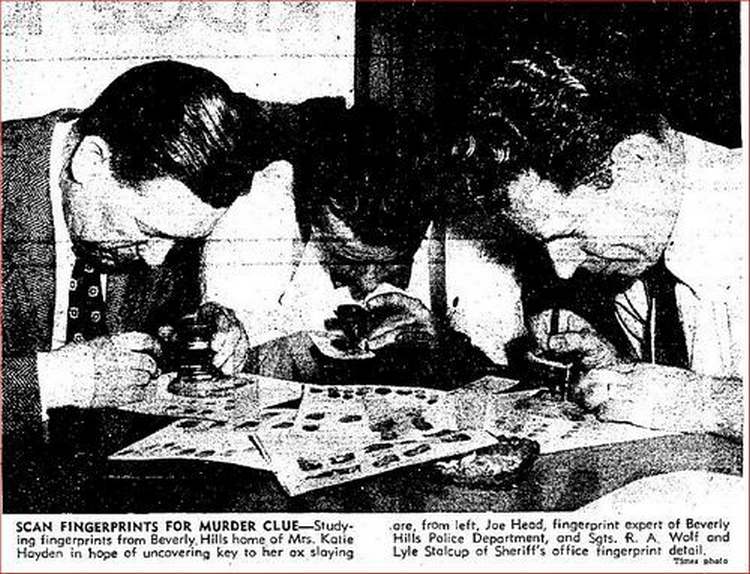

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene. The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone.

The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone. Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

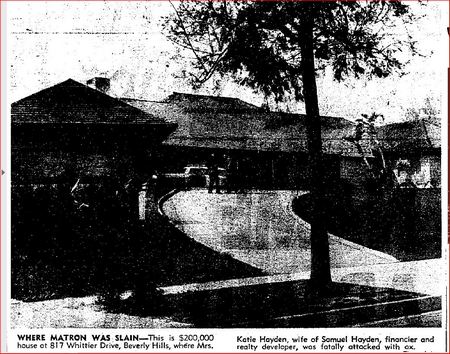

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference.

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference. The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett.

The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett. Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the  Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax.

Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax. So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.”

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.” As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice.

As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice. Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty.

Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty. Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison.

Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison. Evelyn’s brother, Raymond, was satisfied with the outcome of the trustee battle — the bank was his nominee. Ewing’s attorneys were said to be plotting a new strategy to put him back in charge of the estimated $270,000 estate. But losing the trustee fight wasn’t Ewing’s most pressing problem. Rumors of a grand jury and possible indictments were looming large on the horizon.

Evelyn’s brother, Raymond, was satisfied with the outcome of the trustee battle — the bank was his nominee. Ewing’s attorneys were said to be plotting a new strategy to put him back in charge of the estimated $270,000 estate. But losing the trustee fight wasn’t Ewing’s most pressing problem. Rumors of a grand jury and possible indictments were looming large on the horizon. The grand jury indicted Ewing on 13 counts, 4 of theft and 9 of forgery. His constant companion was divorcee Marianne Beaman who seemed to have no problem consorting with a man who may have murdered his wife. Marianne even flatly refused to testify about out-of-town jaunts she and Ewing had taken. Her refusal to speak could lead to a contempt charge.

The grand jury indicted Ewing on 13 counts, 4 of theft and 9 of forgery. His constant companion was divorcee Marianne Beaman who seemed to have no problem consorting with a man who may have murdered his wife. Marianne even flatly refused to testify about out-of-town jaunts she and Ewing had taken. Her refusal to speak could lead to a contempt charge.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual. It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.

It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.