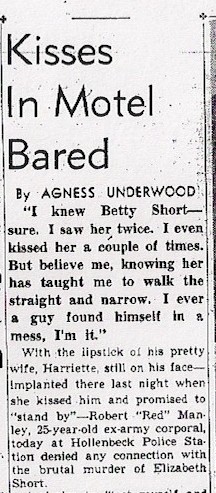

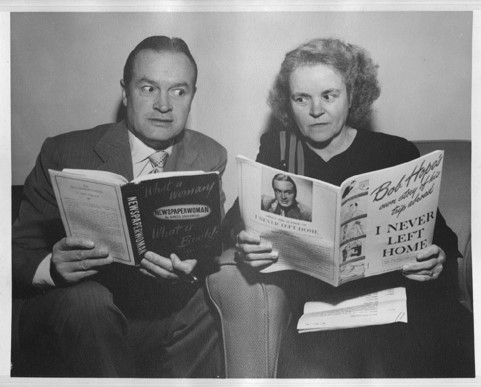

I first encountered Agness “Aggie” Underwood while researching crime in Los Angeles. Aggie’s name appeared many times in various accounts, which piqued my curiosity. I had to know more about one of the few women reporters working in the field during the 1930s and 1940s.

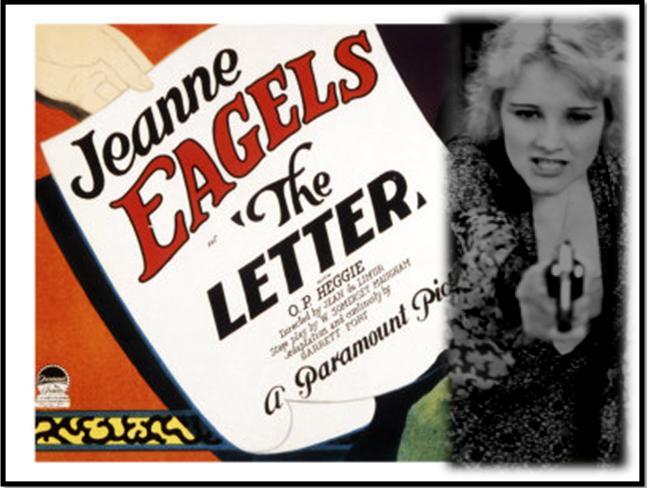

Aggie’s 1949 autobiography, NEWSPAPERWOMAN, was a revelation. Here was a woman who reported on the major crime stories of her day, including the 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia.

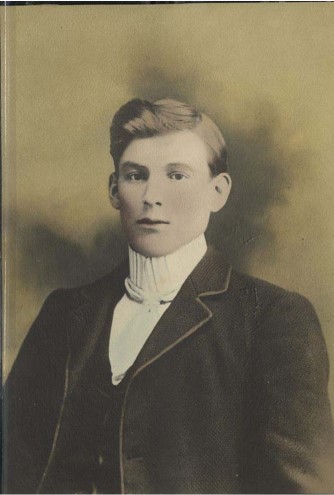

Agness May Wilson was born to Clifford and Mamie Sullivan Wilson in San Francisco in 1902.

Her sister, Leona, followed four years later. By 1904, the family had moved to Belleville, Illinois, and it was there Mamie, 25 years old, died of rheumatism of the heart. Before she died, she had Aggie promise to care for Leona. That is a heavy burden to place on the shoulders of a little girl.

Aggie’s father, Clifford, was a glassblower who traveled for work. After Mamie’s death, he passed Aggie and Leona to relatives. Eventually, relatives placed them in separate foster homes. Aggie fought to keep Leona with her, but her best efforts were no match for the adults who tore them apart. The sisters lost touch.

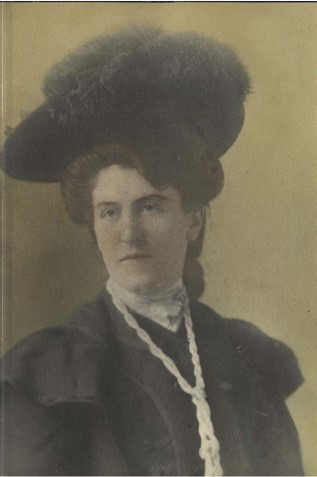

Aggie’s life in the foster home was hard. She struck out on her own in her early teens. Eventually landing in Los Angeles, she worked at the Pig ‘n Whistle downtown. Things looked up when Harry Underwood, a soda jerk at the Pig, proposed to her when a greedy relative threatened to report her for working underage—unless she turned over her entire paycheck. Aggie gratefully accepted Harry’s timely proposal.

We characterize the 1920s as a free-wheeling time when liquor and money flowed. It didn’t hold true for everyone. The Underwoods, like many other families, struggled financially. By 1924, they had two children, Mary Evelyn, and George Harry. They realized they could not make it in Los Angeles, so they traveled out-of-state, seeking new opportunities. During their travels, Aggie located Leona, and they reunited.

The Underwoods returned to Los Angeles, and Leona moved in to the family’s home on the city’s east side. Even with Harry and Leona working day jobs, money was tight. At least Aggie had achieved her dream of having a family. What more could she ask for? How about a pair of stockings?

By October 1926, Aggie grew tired of wearing Leona’s hand-me-down stockings. She went to Harry and asked for the money to buy a pair of her own. He told her they couldn’t afford them.

Incensed, Aggie said if he wouldn’t buy them for her, she’d get a job and buy them herself. It was an empty threat. She hadn’t worked outside the home in several years. What could she do to earn a living?

Before she could turn to the want ads, Evelyn Conners called. She and Aggie had remained close since meeting at the Salvation Army Home several years earlier. Evelyn worked at the Los Angeles Record and got Aggie a temporary job at the switchboard. Evelyn knew Aggie was qualified because they once worked together at the telephone company.

Aggie enjoyed being at the Record, and she hoped to stay through the New Year. She got lucky. Gertrude Price was the women’s editor and wrote an advice column under the name Cynthia Grey. Each year, Gertrude organized a food drive for the city’s poor, and she needed help to fill and deliver the baskets. She asked Aggie if she would stay and help. Without hesitation, Aggie accepted; it meant seven or eight more weeks of steady work.

Aggie assumed she would return to her housewifely chores at in January 1927, but Gertrude had other plans.

Her conscientiousness had not gone unnoticed or unappreciated. Gertrude offered Aggie a part-time job as her assistant. It didn’t pay as well as the switchboard, only five dollars per week. Once she did the arithmetic, Aggie realized she wouldn’t net a dime after she paid a babysitter to watch her kids. Why did she stay if she wasn’t making any money? Aggie didn’t know it yet, but she was in love with the newspaper business.

Throughout 1927, Aggie tackled each task that Gertrude handed her with enthusiasm. In return, Gertrude became her mentor and confidante.

By the time the 1928 holiday season rolled around, Aggie was a fixture at the Record. She again assisted Gertrude Price with the Christmas baskets program. The Underwoods’ financial woes were far from over; but if their holiday was lean, so be it. She felt fortunate to be surrounded by her family.

Ironically, even though Aggie cherished family life, she revealed few details about hers in her autobiography. In fact, she never mentions Harry by name, only referring to her unnamed husband. The reason is simple, she and Harry were divorced a few years before the publication of NEWSPAPERWOMAN. Aggie chose to highlight her professional achievements.

Aggie’s omissions make sense when you consider her position at the time. She was still only a couple of years into her city editorship at the Herald. Personal details might negatively impact her career. I think perhaps the most important thing for Aggie was he desire never to be a “sob sister.” She didn’t want to tug at people’s heartstrings in the copy she wrote for the paper, and especially not in her autobiography. That said, I really wish she had made good on her plan to author a more complete autobiography in her retirement. She never got around to it.

It is no surprise she never wrote about an event that must have devastated her—the death of her sister, Leona, on December 6, 1928. Without Aggie’s input,, we can only speculate on what happened, and what impact it had on her.

Like most families, the Underwoods had a work week routine. December 6 was a Thursday, so Leona dropped her niece and nephew off at the babysitter, as she usually did. While the rest of the family was out for the day, Leona consumed ant paste.

The principal ingredient is arsenic. Ant paste was a common poison found in most households. At twenty-two years old, Leona may have believed that taking poison would be a quick and easy death. She could not have been more wrong. Death by arsenic poisoning is excruciating. Depending on the dose, it can take hours or even days to kill.

Aggie’s established routine was to swing by the babysitter after work, pick up the children, and then go home. When Aggie arrived home, she found Leona. I cannot imagine how Aggie felt. Records show they transported Leona to Pohl Hospital on Washington Boulevard. They admitted her at 3:25 p.m. By 4:00 p.m. her body was in the county morgue. Why did Leona take her life? Her death certificate gives two reasons: “Love affair & financial difficulties.”

Leona’s death notice appeared in the Los Angeles Times the next day. The brief notice said they would hold funeral services on Saturday, December 8, 1928, in the chapel of Ivy H. Overholtser on South Flower Street.

Without input from Aggie, it is difficult to calculate the impact that Leona’s death had on her, but it must have been enormous. Did she feel guilty about failing to honor her mother’s dying wish for a second time? As tragic as Leona’s death was, with two children and a husband to care for, Aggie had no choice but to turn her attention toward the living.

NOTE: The holidays are not a joyous time for everyone. If you or someone you care about is in a crisis, please call 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255 to talk with a caring, trained counselor. It is free, confidential, and available 24/7.