Happy New Year!

When Dorothy French brought Elizabeth Short home in early December, she never expected her to stake a claim to the family’s sofa. Dorothy had simply meant to offer a safer alternative to a seat in the Aztec all-night movie theater—a place to rest for a night or two. No more than that.

But Betty stayed.

She took advantage of the Frenches’ hospitality. They were too kind to put her out, but the tension in the home was growing. Betty (she used Beth and Betty interchangeably) must have felt it.

There’s no record of how they spent Christmas. It would have been the perfect time for Betty to leave San Diego, return to Hollywood—where she had connections, where people at least knew her. But she remained, a guest among strangers. The question is why.

Was she waiting for money? A ride? A man?

Some accounts reduce her stay in San Diego to cliché: drifting, partying, mysterious. It was none of those things. It was stasis. A kind of limbo.

She spent her days writing letters—many of which she never mailed.

One of the most poignant was addressed to Gordon Fickling, dated December 13. She had lived with Fickling—a Navy lieutenant and flier—months earlier in Long Beach. Gordon Fickling.

She wrote:

“I do hope you find a nice girl to kiss at midnight on New Year’s Eve. It would have been wonderful if we belonged to each other now. I’ll never regret coming west to see you. You didn’t take me in your arms and keep me there. However, it was nice as long as it lasted.”

The unsent letter offers a glimpse into her state of mind. It is wistful—a quiet longing for something stable. A safe harbor. And the realization that safety, when it appears at all, is always temporary.

The Frenches’ home had become a kind of refuge. Temporary, but real.

Then, something strange happened.

On January 7, two men and a girl came to the door. They knocked, waited a few minutes, and then ran to a car parked outside.

Betty peeked through the window but refused to answer. She was visibly terrified. When Dorothy asked her about it, Betty was evasive—so much so that Dorothy eventually gave up trying to get answers.

Shortly after, Betty wired Red and asked him to come get her. She was ready to leave San Diego.

He responded the next day:

“Wait and I’ll be down for you.”

NEXT TIME: Elizabeth Short’s life is measured in days.

Archival Note: Little contemporaneous documentation exists regarding Elizabeth Short’s daily life during her stay with the French family in Pacific Beach. Beyond later statements attributed to Dorothy French, and the surviving unsent correspondence, no police reports, diaries, or third-party accounts place Short at any specific location in San Diego between December 8, 1946, and her departure in early January 1947.

Elizabeth Short stepped off the bus in San Diego in early December 1946—alone, broke, and fading into the shadows of the chilly evening.

She walked a few blocks to the Aztec, a 24-hour movie theater. The price of a ticket gave her a quiet and warm place to rest. She dozed off, only to be awakened by the cashier, a woman about her age, Dorothy French.

Dorothy could tell the woman, who introduced herself as Betty Short, was at loose ends. She felt sorry for her, and she knew that a woman sleeping alone in the theater was easy prey. Dorothy invited Betty to come with her to Pacific Beach, where she lived with her mother, Elvera, and her teenage brother, Cory. Betty was welcome to spend the night and get a fresh start the next day.

Nearly two weeks had passed since her arrival on December 8. As the days crawled toward Christmas, the Frenches began to regret their kindness. Like many post-war families, they struggled to make ends meet. Betty hadn’t contributed a cent to the household, and the family was tired of tip-toeing around the sofa as she slept.

She showed no interest in finding a job and spent much of her time writing letters. She had one visitor, a man she introduced only as Red. She told the Frenches he was an airline employee in San Diego who lived in Huntington Park, but stayed at a nearby motel.

The sofa in the Frenches’ modest home was a far cry from the glamorous Hollywood backdrop Betty spoke of, but it provided a measure of stability. According to Elvera, Betty was polite but withdrawn. She offered few details about her past and rarely ventured out during the day. She claimed to have worked at a naval hospital but made no effort to find another job. Over time, Elvera grew uneasy. She had a “premonition” that something was wrong. She described Betty’s presence as moody and unsettled.

She was more shadow than guest.

Dorothy said, “Betty seemed constantly in fear of something. Whenever someone came to the door, she would act frightened.”

Despite the undercurrent of discomfort, the family allowed her to stay through the holidays.

NEXT TIME: Elizabeth Short leaves San Diego.

Archival Note:

Details of Elizabeth Short’s (Black Dahlia) stay with the French family in Pacific Beach are based primarily on contemporaneous police interviews and subsequent press reports. Key accounts include statements attributed to Dorothy and Elvera French following Short’s disappearance and murder.

For more than forty years, Agness “Aggie” Underwood covered the crimes that terrified—and fascinated—Los Angeles. Murderers, mobsters, and corrupt officials all crossed her path. But the moment that set her career in motion wasn’t a gunshot or a headline. It was a pair of silk stockings she couldn’t afford.

In 1926, money was tight. Aggie and her husband, Harry, had a daughter, Evelyn, and a son, George. Her younger sister Leona lived with them and helped with expenses. Still, Aggie wore Leona’s hand-me-down silk stockings. One day, she asked Harry for money to buy a new pair. He said no. Aggie told him that if he wouldn’t give her money for stockings, she’d earn it herself.

She was bluffing. She hadn’t worked outside the home since 1920.

The next day, out of nowhere, her best friend Evelyn offered her a temporary switchboard job at the Daily Record. Aggie grabbed it. The stockings would be hers.

She described her first impression of the newsroom:

“I looked out on a weird wonderland… Shirt-sleeved men attacked beaten-up typewriters, which snarled and balked. Sheets of paper snowed on a central point called the city desk, whatever that meant. Men gyrated through the crazy quilt of splintered desks and tables. It was a jumble.”

The job was supposed to be temporary. But Gertrude Price, the women’s editor (writing as Cynthia Grey), saw something in Aggie and became her mentor. Aggie helped with the annual Cynthia Grey Christmas baskets, and Gertrude encouraged her to learn the business.

Aggie loved the chaos of the newsroom, and she loved being close to a breaking story. In December 1927, the city was horrified by the murder of twelve-year-old Marian Parker by William Edward Hickman, who called himself “The Fox.”

When news of Hickman’s capture in Oregon broke, Aggie couldn’t contain herself:

“As the bulletins pumped in and the city-side worked furiously at localizing, I couldn’t keep myself in my niche. I committed the unpardonable sin of looking over shoulders of reporters as they wrote. I got underfoot. In what I thought was exasperation, Rod Brink, the city editor, said:

‘All right, if you’re so interested, take this dictation.’

I typed the dictation—part of the main running story.

I was sunk.

I wanted to be a reporter.”

She began writing human interest stories, covering fashion and women’s clubs. In May 1931, her first major break came when Charles H. Crawford (a.k.a. the Grey Fox) and reporter Herbert F. Spencer were shot and killed.

Crawford was a former saloon keeper turned vice king. Spencer had worked with a political crusading weekly, the Critic of Critics. They were both involved in the shadowy network known as “The Combination”—a marriage of City Hall and organized crime.

After the murders, David H. Clark, a former deputy DA and candidate for judge, surrendered. But no one had interviewed Clark’s parents. Aggie called every Clark in the phonebook until she found them in Highland Park.

She got the interview. The result: a front-page, above-the-fold story titled Mrs. Clark Says Son is Innocent. Her first double-column byline.

Later, she scored another exclusive with Spencer’s widow. Aggie admitted she was inexperienced—and that honesty earned her the story.

Clark was acquitted. But he drifted. In 1953, he killed a friend’s wife in a drunken fight and died in Chino prison in 1954.

Aggie had found her niche—finding the doors no one else knocked on.

In 1935, she joined the Evening Herald and Express, owned by William Randolph Hearst. She stayed with Hearst the rest of her career.

By 1936, Aggie had a reputation as a reporter who could crack a case. During the Samuel Whittaker case, she interviewed the grieving husband, a retired organist, after his wife Ethel was killed during an apparent hotel robbery.

She staged a dramatic photo of Whittaker pointing his cane at the alleged killer, James Fagan Culver. But as she posed the shot, she noticed something odd: Whittaker winked at Culver.

Was it a tic? No. She waited. Nothing. She discreetly pulled Detective Thad Brown aside:

“Thad, ask that kid why Whittaker winked at him. Don’t let the kid wriggle out of it. Whittaker did wink at him. There’s no mistake about it.”

Brown humored her. Culver cracked. He confessed: Whittaker had staged the robbery, armed Culver with a .38, and planned to kill his wife himself. He did—then turned his gun on Culver. Culver escaped, wounded.

Whittaker was convicted and given life for his wife’s murder. On his way to San Quentin, he said:

“I hope God may strike me dead before I get to my cell if I am guilty of this horrible crime.”

He dropped dead of a heart attack.

In January 1947, Aggie began reporting on the body of an unknown woman found bisected in Leimert Park. She would become known as the Black Dahlia.

Many claim to have coined the name. Aggie said she got it from LAPD Lt. Ray Giese:

“This is something you might like, Agness. I’ve found out they called her the ‘Black Dahlia’ around that drugstore where she hung out down in Long Beach.”

Like it? She LOVED it.

The Jane Doe was soon identified as 22-year-old Elizabeth Short of Medford, MA. Aggie interviewed the first serious suspect, Robert “Red” Manley. Then she was pulled from the case.

She brought in her embroidery hoop while she cooled her heels in the office. Snickers followed. One reporter said:

“What do you think of that? Here’s the best reporter on the Herald, on the biggest day of one of the best stories in years—sitting in the office doing fancy work!”

She was reassigned, then yanked again. And then—she was promoted to city editor.

Dahlia conspiracy theorists say Aggie was close to solving the case. Some believe she was silenced. But promoting her to city editor—the boss of all the Dahlia reporters—was a strange way to shut her up.

Still… what if she was onto something?

When asked later if she knew who killed Elizabeth Short, she said yes—but never named him.

Mercy? Resignation? Maybe both.

Aggie understood something this city still struggles with: some crimes don’t end in arrests. They end in silence.

She covered L.A.’s most deranged crimes. As city editor, she won dozens of awards and the respect of her newsroom. On her 10th anniversary, her crew gave her a giant novelty baseball bat—like the one she kept on her desk to scare off pesky Hollywood types. It read:

“To Aggie, Keep Swinging.”

Reporter Will Fowler said in his autobiography:

“The last thing I remember Aggie saying to her friends who came to celebrate at her retirement party was: ‘Please don’t forget me.’”

She had a bat on her desk and a city full of secrets.

We couldn’t forget her if we tried.

NOTE: If you want to know more about Aggie’s crime reporting, get a copy of the my book, THE FIRST WITH THE LATEST!: AGGIE UNDERWOOD, THE LOS ANGELES HERALD, AND THE SORDID CRIMES OF A CITY.

Welcome! The lobby of the Deranged L.A. Crimes theater is open! Grab a bucket of popcorn, some Milk Duds and a Coke and find a seat. Tonight’s feature is REPEAT PERFORMANCE (1947), starring Louis Hayward, Joan Leslie, and Richard Basehart.

This is the film that Southern California teenager Delora Mae Campbell watched on the night of December 29, 1951. It inspired a dangerous IRRESISTIBLE IMPULSE in her. Click on the title for Part 1 of Delora’s story.

Enjoy the movie!

TCM says:

Just before midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1946, Broadway actress Sheila Page shoots her husband Barney and then rushes to see her friend, William Williams. After a distressed Sheila confesses her deed to William, he suggests they talk to John Friday, Sheila’s producer. As Sheila and William, an oddball poet, are walking up to John’s apartment, Sheila wishes that she could relive the past year, insisting that if she had it to do over, she would not make the same mistakes twice. Upon reaching John’s door, Sheila notices that William has disappeared and then gradually realizes that it is now New Year’s Day, 1946.

In Fort Lupton, Colorado, a fight with your mother could end in grounding. For Delora Campbell, it ended in something far darker. Life in post-war Fort Lupton revolved around church socials, 4-H clubs, and county fairs. Residents followed high school football with a passion, and the Fort Lupton Blue Devils were a source of pride. When the Blue Devils partied under the watchful eyes of adults, they danced to Patti Page’s soulful rendition of The Tennessee Waltz, or did a lively country swing to Hank Williams’ Lovesick Blues.

In the 1950s, no matter where she lived, girls had to adhere to a strict code of behavior. Delora didn’t just test boundaries — she unsettled people. According to her parents, Clem and Francis, they sometimes feared she might harm her siblings. Their fear went beyond the usual sibling squabbles — it sounded like a warning.

Was the pressure to conform to community standards too much for Delora? Or maybe it was one fight too many with her mother, or another battle with her younger brother, Dickie. Maybe she feared she would act on an impulse to harm a family member. Whatever her reasons, at fourteen she ran away from home for the first time.

The court intervened, and a juvenile judge placed her on probation.

Delora’s behavior alarmed everyone — from her parents to school authorities and local pastors. Even her peers may have found her behavior unsettling. One of the biggest fears for a girl Delora’s age was getting a reputation. No worse fate could befall her.

In postwar America, the specter of juvenile delinquency haunted dinner tables from coast to coast. It wasn’t the commie down the street that frightened people; it was their own kid — sulking in the next room, listening to Hank Williams, and thinking dark thoughts.

Historically, when teenage boys acted out, their activities were met with a nod and a wink — the old “boys will be boys” trope. If they committed a serious crime, they might be labeled thugs or delinquents, and could end up in juvenile hall.

Girls faced a different kind of judgment. If they failed to measure up, they weren’t rebellious; they were hysterical, or morally compromised. Moral panic, a genuine fear in the 1950s, punished girls differently. Did Delora worry she might face serious punishment as had other girls who stepped outside expected norms? A girl who rebelled might not go to jail, but to a mental institution — until her hormones, doctors hoped, burned out the madness. Such a girl could count herself lucky if she was released without lasting damage from electroconvulsive therapy, heavy sedation, or ice baths. The belief that emotional instability was baked into the female brain dated back millennia. As one modern paper put it: “Hysteria is undoubtedly the first mental disorder attributable to women…”

Whatever was going on in Delora’s life, something caused her to run again. Was she concerned that she would harm herself or someone else? This time, she vanished for three weeks. Not knowing what else to do, her family sent her to live with her aunt and uncle in Long Beach, California. They may have wanted to spare her local infamy and give her a fresh start — or simply chose to quiet wagging small-town tongues.

The whispers in a small town can kill you.

On the surface, Delora appeared to thrive in her new environment. But was she genuinely happy, or just adapting to survive? On September 1, 1950, the Long Beach Press-Telegram listed her among a group of young people who attended a barbecue dinner where they played games and square danced.

Delora wrote home to tell her parents how much she enjoyed living in Long Beach and going to Woodrow Wilson High School. Francis was surprised — her daughter had never liked school in Fort Lupton.

Delora may have received an allowance, but sometimes when a girl needed extra cash, she took a job babysitting. For several weeks at the end of 1951, she babysat for six-year-old Donna Isbell and her eight-year-old brother, Roy.

On December 29, 1951, Delora walked a few blocks from her aunt and uncle’s home to the Isbell’s to sit with the kids. After the children went to bed, she stretched out on the sofa to watch television. The flickering light filled the room as she watched the 1947 film Repeat Performance.

The movie told the story of a Broadway actress who murders her husband on New Year’s Eve, 1946. As she’s leaving the crime scene, she wishes she could turn back the clock and do the year over — and suddenly finds herself transported to New Year’s Day, 1946.

Delora watched the film to its end, a little after 11 p.m. The house was still.; Donna and Roy were asleep. For a moment, Delora sat and reflected on the film she had watched.

Then the strangest thing happened. She had a vision in which she saw herself committing murder. The vision wasn’t terrifying — it was familiar. She had often felt like choking the life out of her siblings when she lived with her family in Fort Lupton, but she had resisted.

On this night, something inside her felt different—out of her control. She felt the tug of an irresistible impulse guide her as she calmly walked toward six-year-old Donna, sleeping snug in her bed. But first, she needed a necktie.

NEXT TIME: Can Delora resist her impulse?

“Oh my God, he’s killing me!”

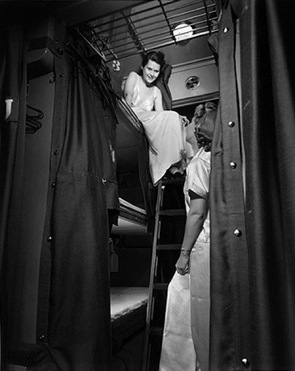

Martha Brinson’s screams tore through the Pullman car, jolting passengers awake in the middle of the night. Moments later, she was dead — murdered in berth 13.

The killer was on the train from Oregon to Los Angeles. But I don’t believe it was Robert E. Lee Folkes.

Wartime paranoia and racism made Folkes the perfect suspect. Black. Working class. Union agitator. Southern Pacific’s second cook. From the moment Martha’s body was discovered, Folkes was railroaded — literally and figuratively.

He worked long shifts in the dining car, sweating over a hot stove, under constant supervision. The train’s conductor later testified there was no opportunity for him to sneak away, let alone murder a woman in her sleep. A physical exam found only flour and grease beneath his fingernails — not blood.

But Folkes was Black. In 1943, that wasn’t a description. It was an indictment.

And he wasn’t just Black. He was political. His father died in the 1920s during the violent white backlash against Black sharecroppers organizing in the Arkansas Delta. His mother, Clara, fled with her children to South Central Los Angeles, chasing safety that never fully arrived.

Folkes grew up in the shadow of that violence. He got his education, then joined Southern Pacific — one of the few decent-paying jobs open to Black men. He started as a fourth cook. He worked hard, and rose to second cook.

By 1942, he was a problem. The company assigned thugs to follow him. They didn’t forget. But Folkes kept pushing, and by January 1943, he’d earned the position of second cook — a step up, despite the pressure from above and below.

So, when Martha Brinson was found dead, the company didn’t have to look far. Despite the pressure, the surveillance, the threats — he remained unbroken. And that made him dangerous.

The detectives dragged him off the train. Stripped him. Locked him in a lavatory. Grilled him through the night. No lawyer. No charges. No real evidence.

Meanwhile, one passenger should have raised every red flag. Harold Wilson, a Marine, had the berth directly above Martha. He was the first to discover the body. He was found with her blood on his clothes. But Wilson wore khaki — and in 1943 America, that was a get-out-of-jail-free card woven into the uniform.

He wasn’t questioned, nor was he detained even though witnesses saw him crawl in and out of his berth. He acted suspiciously. Yet the investigation stayed focused on Folkes.

The trial was a farce. It was never intended to get justice for Martha, the twenty-one-year-old newlywed so callously murdered. The prosecution showed no regard for her as a person. Her death became leverage.

Wilson testified for the prosecution; but he faltered when asked if he could positively identify Folkes. The newspapers labeled Folkes a “zoot-suit wearing negro” — dog-whistle journalism dressed up as coverage. He was never just a suspect. He was a symbol. And symbols don’t get acquitted.

Despite inconsistencies, the unsubstantiated confessions, and a case built more on fear than fact, the jury — nine women, three men — delivered a verdict. Guilty. In Oregon, that meant death.

In 1945, Folkes was hanged. Wilson walked into obscurity.

The courts called it justice.

History calls it something else.

What do you call it?

The case against Robert E. Folkes unfolded against a tense backdrop of wartime fear, racial prejudice, and rising public paranoia. The press inflamed the tensions, describing Folkes as a “zoot-suit wearing negro,” a phrase loaded with menace, meant to reduce him to a caricature and paint him as capable of slashing the throat of 21-year-old newlywed Martha James.

District Attorney L. Orth Sisemore questioned the Black trainmen on board when the train stopped in Klamath Falls, Oregon. Southern Pacific Railroad detectives zeroed in on Folkes. Somewhere between Klamath Falls and Dunsmuir, California, on the night of January 22-23, they pulled him into a men’s lavatory, stripped him, and interrogated him through the night. They released him only for his shifts in the dining car. They treated the sleep-deprived and humiliated man as the prime suspect, even though they did not arrest him.

Not everyone on the train believed in Folkes’ guilt. The conductor stated Folkes couldn’t have committed the murder. According to him, the configuration of the diner and Folkes’ workload made it impossible. He pointed instead to another passenger—Harold Wilson, a white Marine who had occupied the berth above Martha’s. Given his proximity to the victim, Wilson should have been a suspect. Instead, they treated him as a material witness and quietly removed him from suspicion.

When the train arrived in Los Angeles on January 23rd, LAPD detectives took Folkes into custody. He was sleep-deprived, unrepresented, and vulnerable. They bounced him between Central Jail and Police Headquarters, questioned him without legal counsel. LAPD officers phoned Linn County District Attorney Harlow Weinrick in Oregon to report that Folkes had cracked.

But in every official statement before the supposed confession, Folkes had denied guilt. He did not sign or review the alleged confession. The investigators did not record it; the lawyer did not witness it; it seemed coerced.

LAPD’s interrogation practices at the time weren’t just aggressive — they were dangerous. Coercion took many forms: physical abuse (beatings), psychological pressure (threats against family, exploiting a suspect’s fear of mob violence or racial prejudice), or improper inducements (offering alcohol, sexual access, or other rewards). Days earlier, the department faced scrutiny after Stanley Bebee, a 44-year-old accountant, died following a brutal beating in custody for public intoxication. The jury acquitted the officers. However, the case highlighted the LAPD’s violent methods.

Although the Folkes investigation showed no proven evidence of bribery or case-fixing, the environment surrounding his interrogation was badly compromised. Some interrogators used coercive tactics, custody chains were blurred, and courtroom conduct varied from irregular to unethical. It is easy to conclude that the LAPD mistreated Folkes while he was in custody.

There was no physical evidence linking Folkes to the crime. No eyewitness identified him. But the so-called confession was enough for an arrest. Initially, Folkes refused to waive extradition to Oregon. But during arraignment before Judge Byron Walters, he relented and agreed to return north for trial.

On the night of January 29, 1943, accompanied by Sheriff Clay Kirk of Linn County and two Southern Pacific special agents, Folkes boarded a train for Albany.

His trial began in April. The jury of eight women and four men was unusual. In Oregon, women could serve only if they filed a written declaration, making their presence more striking. Their makeup may have influenced how testimony was weighed.

The state’s only link between Folkes and the murder was the testimony of Harold Wilson—the Marine who had been in the berth above Martha. His description of the suspect was vague: “a swarthy man in a brown pinstriped suit.” He never identified Folkes. And witnesses saw Folkes in the kitchen, dressed in his work clothes, minutes after the murder occurred. The police never found a brown pin-striped suit.

Though the defense objected, the court admitted two alleged confessions into evidence. Many red flags riddled both confessions. On April 16, LAPD Lieutenant E. A. Tetrick testified Folkes gave an oral confession after officers brought him a pint of whiskey and let him visit his common-law wife, Jesse. Circuit Judge J.G. Lewelling called the practice “reprehensible,” though he insisted Folkes was sober and in “full possession of his faculties.”

Dr. Paul De River—LAPD’s controversial police psychiatrist—later infamous in the Black Dahlia case, testified that he spoke with Folkes after the confession. According to De River, Folkes “may have had a drink or two,” but was not intoxicated. No one asked how he had reached that conclusion. De River also reported no physical injuries on Folkes’ body and described him as “in good physical condition.”

On cross-examination, Folkes’ attorney, Leroy Lomax, asked if De River had referred to Folkes as an exhibitionist. De River replied, “I might have said that.”

The defense rested its case on April 20, 1943.

The jury began deliberations but returned to the judge saying they couldn’t reach a verdict. He ordered them to continue and provided army cots for them to sleep on inside the courthouse. After thirty hours of deadlock and courtroom drama, the jury filed in at 3:13 p.m. on April 22. Their verdict: guilty of first-degree murder. Death was mandatory.

“I know it was a fair and impartial trial,” Folkes said afterward. “I’m sorry the jury thought I did it, as I didn’t, and I’m sorry my mother and Jesse had to go through this.”

In a letter to his mother, Clara, he was more candid:

“I was not convicted on evidence. I was convicted through prejudice.”

Folkes added: “I truly believe that I could take any one of those jurymen that convicted me, or even the judge who heard the case, and on the same grounds, either one of those people could be placed in front of a Negro jury and convicted. Of course, this incident will never happen, but I assure you it is amazing what prejudice can do.”

On November 5, 1944, a group of Los Angeles clubwomen formed the Robert Folkes Defense Club and pledged to raise $2,000 to bring his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court declined to hear the appeal on November 23.

Lomax worked tirelessly, appealing to the Governor of Oregon to commute the sentence to life. The governor refused.

On January 5, 1945, at 9:13 a.m., Robert E. Folkes died in Oregon’s gas chamber for a crime he insisted he did not commit.

NEXT TIME: In the conclusion of “The Lower 13th Murder Case”, we’ll examine the case more closely—and ask whether wartime prejudice condemned an innocent man.

On the night of January 22, 1943, a young woman boarded the Klamath, from Oregon, a crowded wartime train bound for Los Angeles. Her name was Martha Virginia Brinson James. She was twenty-one, newly married, and hopeful—one of thousands of wives trying to reconnect with their men in uniform.

Before the sun rose, she would be dead—her throat slashed in a sleeper car while dozens of passengers slept nearby. The man accused of the crime confessed, then recanted. No one saw him do it. No physical evidence tied him to the murder. Yet he stood trial, and the country watched.

Martha and her husband, Richard, would have preferred to travel together, but heavy wartime ridership made it impossible. She socialized with other Navy wives, each of them looking forward to a reunion, then she retired to a lower berth, number 13.

About 3:00 a.m., people in the sleeping car heard a woman scream, “My God, he’s killing me!” It was Martha. Bleeding, her throat cut, she tumbled from her berth and stumbled to a nearby lavatory where she died.

Private Harold Wilson, a Marine, occupied the berth above Martha’s. When he heard the scream, he opened his curtains in time to see a burly, black-haired man in a brown pin-stripe suit rushing down the aisle.

Detectives E. A. Tetrick and Richard B. McCreadie met the Klamath at Los Angeles Union Station. Oregon authorities requested they hold the train’s second cook, Los Angeles resident, Robert Folkes, as a material witness. Due to a legal technicality, they booked him on suspicion of murder instead.

Folkes, a 20-year-old black man, came to California from Arkansas with his mother and siblings in the late 1930s The family was part of a large influx of people fleeing the Jim Crow south. They heard that Los Angeles offered more opportunities—which was true to a point. There were restrictions that forced blacks to live in segregated, neighborhoods. Like many of the transplants, Folkes’ family landed in South Central.

Wilbur Brinson, Martha’s father, made a good living as a manager for a coal company. Her mother, Grace, was a housewife and the family had a live-in black maid. They lived on North Shore Road in Norfolk, Virgina. The homes on North Shore Road were large, situated on beautiful tree-lined plots of land; walking distance from the Lafayette River, near the Chesapeake Bay. Nothing about Martha’s background could have prepared her family to lose her in such a brutal way.

LAPD detectives conducted a background check on Folkes; standard procedure for anyone involved in a murder case. They discovered he had a police record. On August 24, 1940, he was arrested on suspicion of assaulting a white woman. She refused to prosecute. On July 30, 1941, police arrested Folkes on a drunk charge after he entered a home and went to sleep. On December 28, 1942, Folkes cut the screen on a house in which three women slept.

During initial questioning, Folkes made a bizarre statement. He said, “I didn’t do the actual killing.” But then he confessed to Captain Vern Rasmussen of LAPD’s homicide detail. A confession he immediately retracted. Something about Folkes’ demeanor made detectives think he might be protecting someone.

Police wanted Folkes to open up, so when he promised to tell them “something important” if they allowed him to visit his wife at home, they took him there. Once the visit was over, he reneged on his promise and continued to maintain his ignorance of the murder.

Police psychiatrist Paul De River questioned Folkes and pronounced him “sane, but a definite exhibitionist.”

On January 27th, District Attorney Harlow Weinrick of Linn County, Albany, Oregon, told the Associated Press he had filed a first-degree murder charge against Folkes. Los Angeles would have to send him there.

Folkes continued to flip-flop. The authorities would not immediately release the details of his confessions until Oregon officials arrived. However, sources said Folkes admitted whetting a boning knife before going to Lower 13, where he attacked Martha James. According to Detective Rasmussen, Folkes admitted getting drunk on the train and walking through Car D, where he noticed Martha sitting up in her berth. He said she “appealed to him.”

He set his alarm clock for an hour earlier than usual, 3 a.m., and when he got up to prepare the galley stoves, he picked up a knife and sharpened it. He slipped it up his sleeve.

He walked past Lower 13 several times to determine if Martha was awake. She was sleeping. He unbuttoned the curtain, and climbed into the berth. Martha resisted and screamed. He cut her throat.

One story Folkes told police was that a man paid him $1000 to kill Martha. Nothing supported that story.

Once Folkes was identified as the chief suspect, much of the reportage focused on his race and referred to him as a “zoot suit wearing negro”—a highly pejorative characterization. Racial and cultural tension in Los Angeles was high, and zoot suits exacerbated the situation.

A zoot suit was an oversized style of clothing. Long jackets with heavily padded shoulders, wide lapels and baggy trousers pegged at the ankles. Wearers accessorized the suit with a wide-brim hat and a watch chain. Many people considered the zoot suit unpatriotic. Cloth was rationed, so the zoot suit was seen as wasteful. In the minds of most zoot suiters their clothing was a form of self-expression, defiance, and protest.

The suit resulted in racialized policing. Wearing a zoot suit was a sure way to bring unwanted attention from the police. Fueling the already volatile situation, the media linked crimes to zoot suiters and stoked fear and prejudice.

Folkes made another confession, which he refused to sign. He said, “If I were not guilty, I would not make this confession. I have kept my word. As long as she (the stenographer) has it down and I read it thoroughly and understand it, I will be willing to take the medicine, which the killer should take.”

About the murder, he said: “It was all in a fog to me. I reached first with my right hand, then with my left, but evidently in my mind I figured. . . And there is where I killed her . . I guess I cut her . . .”

Chief Deputy Clay E. Kirk of Linn County, Oregon, arrived in Los Angeles to take Folkes into custody and return him north. Folkes waived extradition.

Soldiers armed with submachine guns patrolled the Albany train station platform to discourage any attempt to harm the prisoner. To ensure his safety, they took Folkes off the train at Springfield, 48 miles south of Albany, and transported him to the jail by car.

Not everyone took Folkes’ guilt for granted. The California Eagle, a newspaper serving Los Angeles’ black community, reported that a spokesman for a Citizens Committee, said, “Grave doubts exist as to Folkes’ guilt and it is imperative that his constitutional rights to a fair trial be safeguarded by seeing to it that he has competent counsel.”

The Eagle also reported that despite Folkes’ conflicting statements and numerous confessions, the physical evidence was non-existent. Detailed examinations of his clothing and chemical analysis of scrapings from his fingernails and shoes showed no blood or other incriminating evidence of any kind was found.

Hollywood stars including Ben Carter, Hattie McDaniel, and Louise Beavers came forward to support Folkes. They planned to appear at a dance at an Elks Club to raise money to fund his defense.

The marine who saw a man fleeing the scene was vague. He couldn’t identify Folkes—and he couldn’t explain how one minute he was in his pajamas in his berth, and the next he was fully dressed and chasing the killer.

None of Folkes’ co-workers believed him guilty. He performed all his usual duties on the morning of the murder. Nothing in his demeanor was unusual.

Folkes said he would prove his innocence at his trial in April.

NEXT TIME: Folkes’ trial and the conclusion of The Lower 13th Murder case.

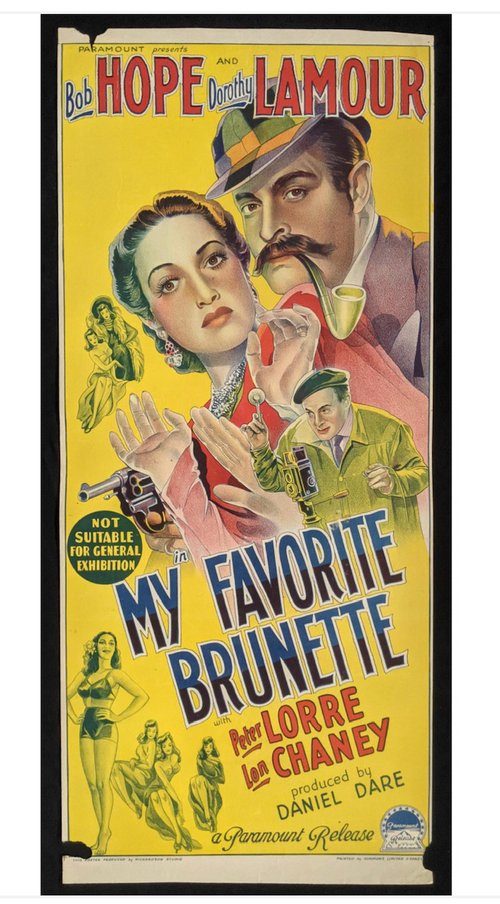

Welcome! The lobby of the Deranged L.A. Crimes theater is open! Grab a bucket of popcorn, some Milk Duds and a Coke and find a seat. Tonight’s feature is MY FAVORITE BRUNETTE, because every now and then we need a laugh. It is a film noir parody starring Bob Hope, Dorothy Lamour, Peter Lorre, and Lon Chaney–with Alan Ladd in a cameo role. There’s also a surprise cameo at the end.

TCM says:

In San Quentin prison, baby photographer and amateur detective Ronnie Jackson, awaiting execution for murder, tells the press the story of his demise: Ever aspiring to be a detective, Ronnie invents a keyhole camera lens and buys a gun, hoping to work for private detective Sam McCloud, whose office is across from Ronnie’s studio in San Francisco’s Chinatown. When Sam goes to Chicago, he leaves Ronnie behind to man the telephones, and Ronnie takes the case of Carlotta Montay, a beautiful brunette whose uncle, Baron Montay, is in trouble.

Enjoy the movie!