We expect goblins, ghosts, and ghouls to roam the streets on All Hallows Eve; what we don‘t expect is murder.

October 31, 1957, was a school night. Kids scored their Butterfinger bars and homemade caramel apples and were home in their jammies at a decent hour. Thirty-five-year-old Peter Fabiano, his wife Betty, and teenage stepdaughter, Judy Solomon, had just retired for the night. Peter’s stepson, Richard Solomon, had left earlier to return to his navy base in San Diego. The family wasn’t expecting any callers when the doorbell rang shortly after 11 p.m.

Peter got out of bed and went to the door. Betty heard him say “Yes?” Then he said, “Isn’t it a little late for this?” She heard, but didn’t recognize, two other adult voices. “One sounded masculine and another like a man impersonating a woman.” Then Betty heard a noise that “sounded like a pop.” The noise brought her and Judy out of their beds in a hurry. They found Peter lying on his back, just inside the front door.

Judy ran two doors down to Bud Alper’s home. She banged on the door until he answered. Bud, a member of the Los Angeles Police Department, Valley Division, called his office for assistance. Several officers arrived within minutes.

They transported Peter to Sun Valley Receiving Hospital, where he succumbed to massive bleeding from the gunshot wound.

Detectives found no spent shells, nor did they find evidence that the shooting was part of an attempted robbery. Betty told them she and Peter married in 1955. Together they ran two successful beauty shops and, as far as she knew, he had no enemies.

A fifteen-year-old boy witnessed a car leave the neighborhood at a high rate of speed around the time of the shooting. He had no other information for police.

Peter’s murder resembled a gangland hit, so the police dug into his background. Peter had a minor record for bookmaking in 1948–nothing that connected him to L.A.’s underworld.

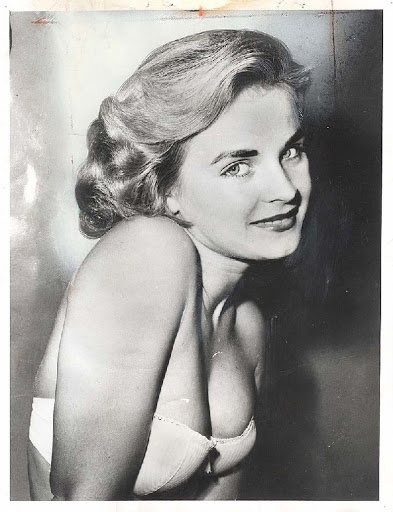

Detectives learned Peter was born in Lansing, Michigan. He enlisted early in the Marine Corps and served with distinction in the Pacific during the war. Discharged in Los Angeles, he decided to stay. He worked for a while as a bartender—which is how he met Betty, an attractive redheaded divorcee.

Nothing about Peter’s background suggested he might get into the beauty business. Betty urged him to study cosmetology under the G.I. Bill. His good looks and easy manner made him a natural for the business.

Peter and Betty became partners in the beauty shop. It did so well, they opened a second location. They married in 1954, and settled in Pacoima.

Only one thing kept their marriage from being perfect. Betty’s relationship with Joan Rabel, a 40-something divorcee and occasional cosmetics saleswoman.

The two women knew each other before Betty met Peter. There was something about the way they acted toward each other that made Peter uncomfortable. He and Betty argued about it, and he said he did not want Joan coming around anymore. Betty told him he had no right to tell her who she could be friends with, and she walked out on him. When she returned a month later, she said she wouldn’t see Joan again.

Detectives questioned Joan. She admitted she hated Peter, but not enough to kill him. Besides, she didn’t have a car, and police were convinced the killer had escaped in one. She also said she had never touched a gun.

When they followed up on Joan’s statement, they found out she told the truth about not having a car of her own; however, she neglected to mention she had borrowed one from a male friend. An old green sedan, which may have been the same vehicle spotted at the murder scene. The car’s owner noticed extra miles on the odometer—just enough to make a trip from Pacoima to downtown. Joan brushed off the detectives, saying she had forgotten borrowing the car. Also in her favor was the fact that Joan was as tall as Peter. How could she have convinced him, even wearing a disguise, that she was a trick-or-treater?

Six weeks after the murder, police heard from a diminutive widow, 43-year-old Goldyne Pizer. She admitted to the slaying and told LAPD Detective Sergeants Charles Stewart and Pat Kelly, “It’s a relief to get it off my mind.” She said a friend of hers, Joan Rabel, talked her into committing the crime.

Friends for four years, Goldyne and Joan planned the murder for three months. “All we talked about was Peter Fabiano.” Joan described the victim as, “… a vile, evil man—one who destroyed all the people about him. I developed a deep hatred for him.”

On September 21, Goldyne purchased a .38 Special from a gun shop in Pasadena. She told the man behind the counter she needed the weapon for “home protection.” A few days later, Joan drove Goldyne back to the shop, where they picked up the gun, which had two bullets in it. Joan paid for the gun, but Goldyne kept it until Halloween night when Joan picked her up in the borrowed car.

“Joan came over to my house with some clothing—blue jeans, khaki jackets, hats, eye masks, makeup, and red gloves. We dressed up, got in the car, and drove to Fabiano’s home, arriving there about 9 p.m.”

The women waited until the lights went out. Goldyne said, “I rang once and when nothing happened rang again.” Fabiano expected to see Halloween stragglers looking for one last treat before heading home. Instead, he saw Goldyne. She brought the gun up with both hands and fired.

“I ran to the car and Joan drove to Mrs. Barrett’s home,” Goldyne said. [Joan borrowed Margaret Barrett’s car to commit the murder.] “We left the car on the street, separated, and walked to our homes. Joan said, ‘Forget you ever saw me’.”

The County Grand Jury returned indictments against Goldyne and Joan for Peter’s murder. Goldyne wept as she told the Grand Jury of the weird killing. She explained Joan incited her to commit the murder of a man she didn’t know by painting a picture of the victim as a “symbol of evil.”

Joan declined to testify.

Rather than face trial, on March 11, 1958, Goldyne and Joan pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and were sentenced to 5 years to life in prison.

What about a motive? Why did Joan want Peter to die? Simple. Peter stood in the way of Joan’s plan to get much, much closer to Betty. She hated him for breaking up her relationship with Betty.

The newspapers alluded to Joan’s sexual orientation. Reports described her as jealous of the Fabiano’s relationship. Readers understood the subtext. Homosexuality was illegal in California—which may be why Joan accepted a plea deal. The doctor who examined Goldyne characterized her as a passive person who became “putty in the hands of Mrs. Rabel.” The same doctor described Joan as “schizoid.”

I don’t know when Goldyne left prison. Even though she fired the gun, she was a pawn in Joan’s revenge plot. Of course, that doesn’t minimize her guilt. Goldyne passed away on February 11, 1998 in Los Angeles.

Joan Rabel vanished. I could not find a trace of her. Her plan robbed Peter of his life, Betty of her husband, and Judy and Richard of their stepfather. I hope she spent a long time in prison.

Betty continued as a hair stylist, joining a salon in Studio City in 1962. She never remarried. She died in Palm Desert, California on August 9, 1999.

Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the

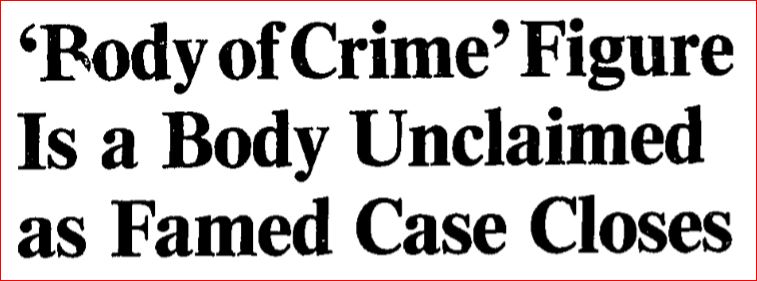

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the  Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax.

Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax. So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.”

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.” As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice.

As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice. Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty.

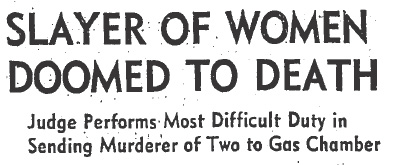

Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty. Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison.

Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison. By now may be wondering what Marion’s criminal behavior in Ohio, Nebraska, and Colorado has got to do with Los Angeles. Simple. Like many others before him, following his release from prison the ex-con moved to Los Angeles–land of bright blue skies, sunny beaches and, in Marion’s case, third chances. Prison may have mellowed him, and perhaps it did–for a while. From 1940 to 1957 if he committed any crimes they weren’t serious enough to get his name into the newspapers. Unfortunately, Marion proved to be incapable of keeping his life on track.

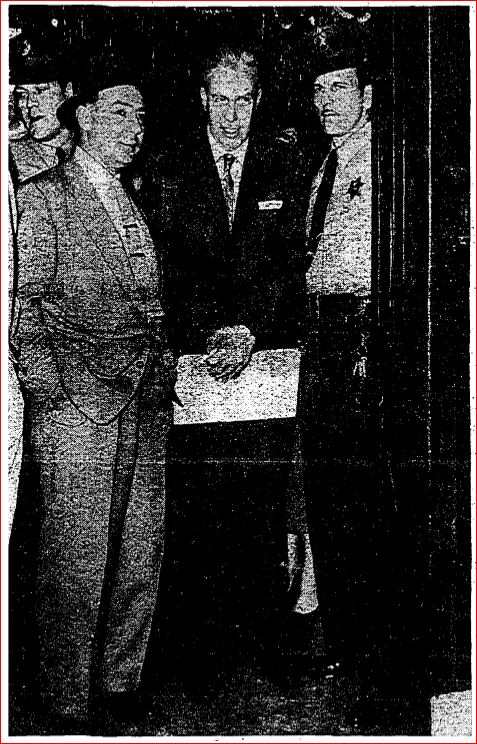

By now may be wondering what Marion’s criminal behavior in Ohio, Nebraska, and Colorado has got to do with Los Angeles. Simple. Like many others before him, following his release from prison the ex-con moved to Los Angeles–land of bright blue skies, sunny beaches and, in Marion’s case, third chances. Prison may have mellowed him, and perhaps it did–for a while. From 1940 to 1957 if he committed any crimes they weren’t serious enough to get his name into the newspapers. Unfortunately, Marion proved to be incapable of keeping his life on track. Lieutenant Gebhart took the suspect to Homicide Division. As they drove, the suspect said: “I hope you have me for murder. I shot that #@$%&*cop and I intended to kill him. If I had an opportunity I would kill all of you. … I tried to shoot him in the heart. … I shot him with a .32 and I didn’t think it would do that much damage, but I hoped it would.”

Lieutenant Gebhart took the suspect to Homicide Division. As they drove, the suspect said: “I hope you have me for murder. I shot that #@$%&*cop and I intended to kill him. If I had an opportunity I would kill all of you. … I tried to shoot him in the heart. … I shot him with a .32 and I didn’t think it would do that much damage, but I hoped it would.”

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

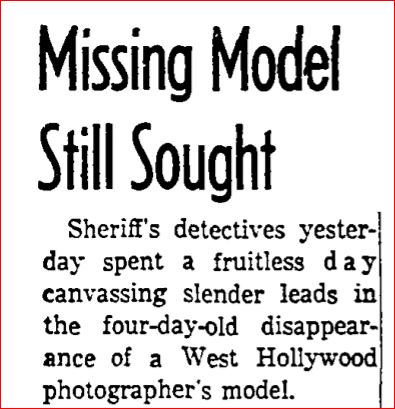

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.