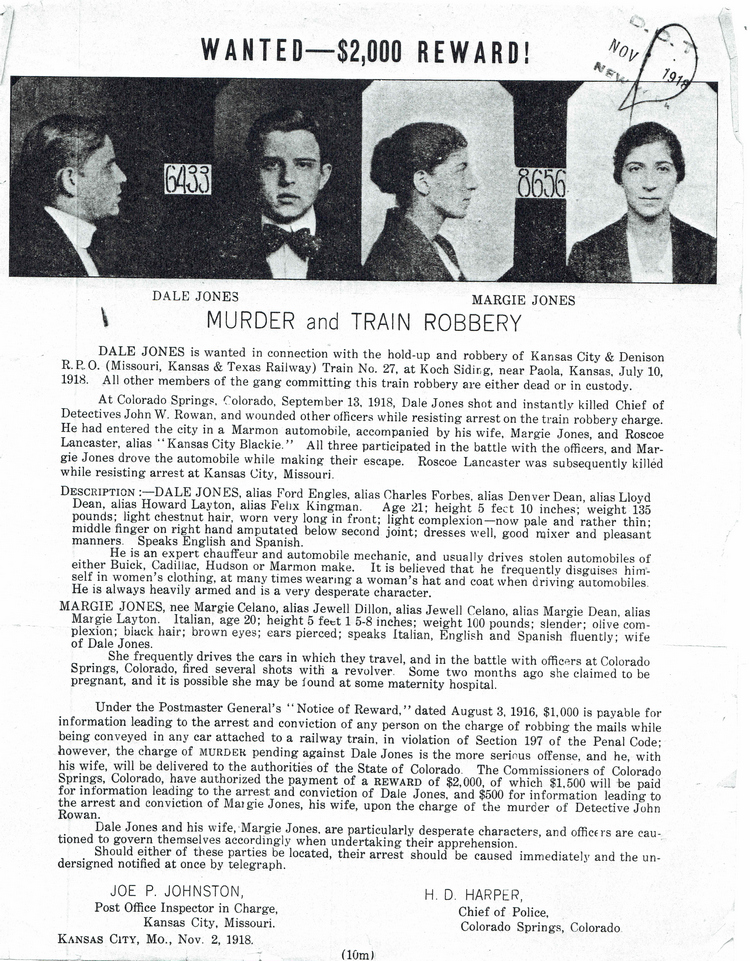

On December 26, 1930, readers of the Los Angeles Times awoke to the dismaying headline: “Holiday Brings Orgy of Crime”. Apparently, not all Angelenos with goodwill toward their fellow man or woman. The article was a litany of Christmas Eve and Christmas Day misdeeds that began with the shooting of a police officer.

Allen G. Adcock of the Hollenbeck Heights division during the early morning hours of Christmas Day. Officer Adcock had been directing traffic during a fire at Macy and Gelardo streets when a car containing two men ignored his command to halt and blew through the intersection at a high rate of speed. Apparently, Adcock “badged” a civilian, Earl H. Pfeifer, and commandeered the man’s auto to pursue the suspects. With Pfeifer at the wheel, Adcock stood on the running board of the car and held on for dear life. One of the fleeing men leveled his weapon at Adcock, who then whipped out his own pistol. The two men fired simultaneously and a bullet from the suspect’s gun struck a glancing blow on Adcock’s head, which knocked the cop off of Pfiefer’s running board.

Pfiefer stopped to render aid to the fallen policeman, and the suspects escaped. A subsequent investigation showed that the two suspects were bandits who had held up Irwin Welborn of West Twenty-ninth Street. They drove him out to Long Beach and then robbed him of $2 and his car.

At Pacific and O’Farrell Streets in San Pedro, someone slugged Zack Zuanich, a local poultryman, on the head with a wooden club. They took Zuanich to the San Pedro General Hospital in serious condition. The attacked appeared random.

Los Feliz Bridge (aka Shakespeare Bridge) [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

Two cowardly bandits, turned rapists, dragged Maxine Ungeheur (20) and her younger sister Thelma (19) out of a car under the Los Feliz Bridge (aka Shakespeare Bridge) and savagely attacked them. The sisters were being driven home by Roland Oakley, a Griffith Park employee, following a Christmas Eve soiree. Oakley slowed his auto near the bridge, and the bandits stepped out from a clump of trees and threatened the girls and Oakley with guns. Oakley, under threat of death, stood helplessly by as the bandits ravaged the girls. The cops located clues at the scene, in particular a leather glove believed to have been worn by one attacker. Detective Lieutenants Hoy and Kriewald of the Lincoln Heights Division hoped that the clue would lead to the arrests of the men involved in the assaults.

Besides all the other mayhem occurring in and around the city, there was a spate of holiday burglaries for cops to contend with. Two men were discovered plundering a store on Huntington Drive by Officers Cooke and Carter, and a citizen, A. Burke. Upon being found out, the two crooks attempted to high-tail it to freedom. Officer Cooke fired at the fleeing suspects and the citizen, A. Burke, unloaded a charge of birdshot from his shotgun. Both suspects dropped to the ground, but one of them scrambled to his feet and made good his escape. Officers captured the other crook and he gave his name as Bernave Palacios. They held him on suspicion of burglary.

Two bandits held up Benjamin Caldron in his South Western Avenue flower shop on Christmas morning robbed him of $110.

The Ungeheur sisters were not the only women who were victims of rape, or attempted rape, over the Christmas holiday. Mrs. Dorothy Loustanau was walking near the corner of Ninetieth Street and Avalon Boulevard when a man drove an automobile up to the curb and leaped out. Snarling that he would beat her to death if she resisted, he clapped his hand over her mouth and pinioned her arms while he attempted to force her into his car. Dorothy struggled desperately and stayed out of the car. Her attacker, enraged at his victim for putting up a fight, tried to drag her into a vacant lot, but Dorothy broke free and screamed for help. Her assailant fled the scene.

Lillian Rosine, of 1322 Cherokee Avenue in Hollywood, was driving down Las Palmas Avenue with a friend, Earl Marshall, when a bandit leaped onto the running board of her car. The bandit produced an automatic weapon and commanded Lillian and Earl to stick up their hands. Lillian became furious with the brazen bandit and instead of complying with his order, she leaned in front of Earl and shoved the bandit in the face!

Thrown off balance, the crook fired, and the round grazed Earl’s head, inflicting a four-inch wound in his scalp. Lillian screamed and stomped down hard on the gas. The bandit tumbled off of the running board, stood up, and then walked nonchalantly up Selma Avenue. Lillian dashed to the Hollywood Receiving Hospital a few blocks away, where doctors treated and dressed Earl’s wound. The bandit remained at large.

![Hollywood Receiving Hospital c. 1936 [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/00065893_hollywood_receiving.jpg)

Hollywood Receiving Hospital c. 1936 [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

I’ll wrap up the orgy of crime with the murder of Jose Lopez (45). Lopez died in Georgia Street Receiving Hospital from wounds received in an attempted hold-up and fight. Lopez’s friend, Jose Ayala, told the cops that two men accosted him and Jose early Christmas morning and beaten with clubs. Ayala did his best to describe the killers, but a blow to the mouth knocked him unconscious early in the struggle.

I hope that your holiday is going better than the unfortunates in the above post. Be well, happy, and stay safe. — Joan

![Hollywood Receiving Hospital c. 1936 [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/00065893_hollywood_receiving.jpg)