It was a few minutes into August 9, 1969, and Mrs. Seymour Kott of 10170 Cielo Drive heard a series of claps. She couldn’t identify the source or location of the noise and so she went back to sleep.

Winifred Chapman, maid for director Roman Polanski and his wife actress Sharon Tate, arrived at their home at the far end of Cielo Drive at 8:30 a.m. to begin work. The quiet street is a cul-de-sac between Beverly Glen and Benedict Canyon. Birds chirping, a dog barking or the occasional coyote call are about the only sounds you hear; but there was an unnatural quality to the stillness that morning.

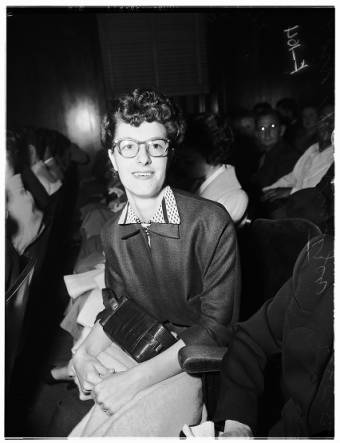

Winifred Chapman

Winifred saw a white two-door Rambler sedan in the driveway. She didn’t recognize the car and approached it with caution. She saw a young man behind the wheel slumped over toward the passenger seat. There was blood on his shirt and his left arm.

As she continued toward the sprawling home she found the body of Voytek Frykowski on the front lawn.

Under a fir tree, about 20 yards away, she found Abigail Folger’s bloody body.

The horror followed Winifred into the living room. Sharon Tate, 8 ½ months pregnant and dressed in her bra and bikini bottom, had a bloody nylon cord wrapped around her neck. The cord looped around a beam in the ceiling. Someone tied the other end of the cord around Jay Sebring’s neck and placed a black hood on his head.

Terrified, Winifred ran to a neighbor’s home for help. Fifteen-year-old Jim Asim was preparing to leave when she stopped him screaming, “there’s bodies and blood all over the place!”

Victims being transported to morgue

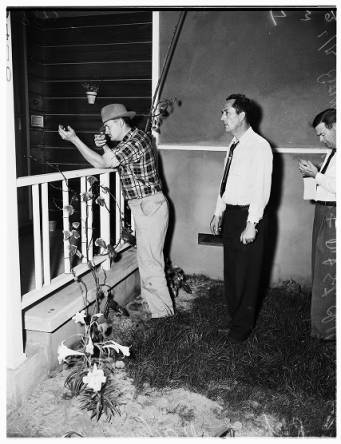

Asim, a member of Law Enforcement Troop 800 of the Boy Scouts, called the police. Moments later six LAPD black and whites roared up Cielo Drive to its end where there is a wire gate outside the Polanski residence. Guns drawn; the officers entered the property. They heard a dog howling behind a guest house and a man’s voice shouted for it to be quiet.

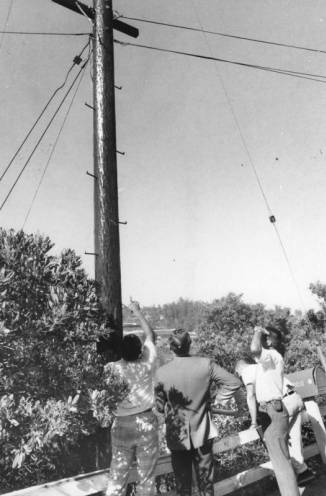

Wire gate outside Polanski residence.

In the guest house, nineteen-year-old William Etson Garretson looked up to see his doorway crowded with police. They had shotguns trained on him. He was still half asleep, dressed only in pin-striped bell-bottoms. He did not understand why the cops were there.

After several hours of questioning, they took Garretson into custody and arrested him on suspicion of murder. As the only living person on the premises he was the obvious suspect. Yet there was no physical evidence tying him to the deaths.

Police in Garretson’s hometown of Lancaster, Ohio, told LAPD investigators the kid had committed one offense of little consequence. He received a two-year suspended jail sentence in 1967 for contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Mary Garretson, his 42-year-old mother, told police her son left home in October 1968 “without saying goodbye but had written saying he hoped to return home soon.”

William Garretson (center)

Garretson was a quiet kid and lacked the personality to take control of five adults and viciously murder them.

Garretson didn’t even work for the Polanski’s and had only a vague notion of who they were. He lived in the guest house and kept to himself. The property owner, Rudy Altabelli employed him as a caretaker

In Europe when he received the news of the slayings, Altabelli offered no reason for the murders.

Someone cut the telephone lines into the home, which suggested a plan. There was no weapon at the scene except for pieces of a pistol grip.

Telephone line

It was 1969, so it was no surprise that all the victims wore “hippie type” clothes – their mode of dress was enough for the police to search for drugs. They found none. As far investigators could tell nothing appeared to be missing – which ruled out robbery as a motive.

They found evidence of a struggle and wondered; why had not one of the five victims escaped the carnage?

As LAPD detectives followed scant leads to dead-ends, talk on the street was of the upcoming Aquarian Exposition in White Lake, New York. Many people from L.A. planned to make the trek. Billed as three days of peace and music, the festival promised to be amazing. The younger generation had a chip on its shoulder and something to prove. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll. Fuck Nixon. Fuck the War. Life is beautiful, man.

The dream was already dead.

NEXT TIME: Two more murders.

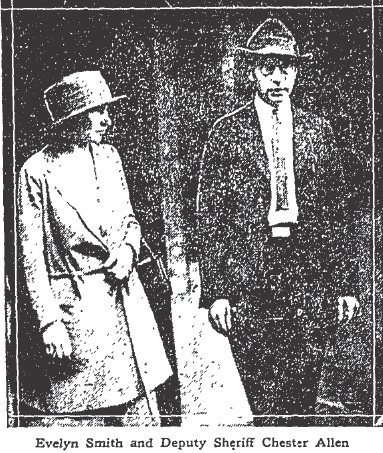

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.”

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.” Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying.

Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying.

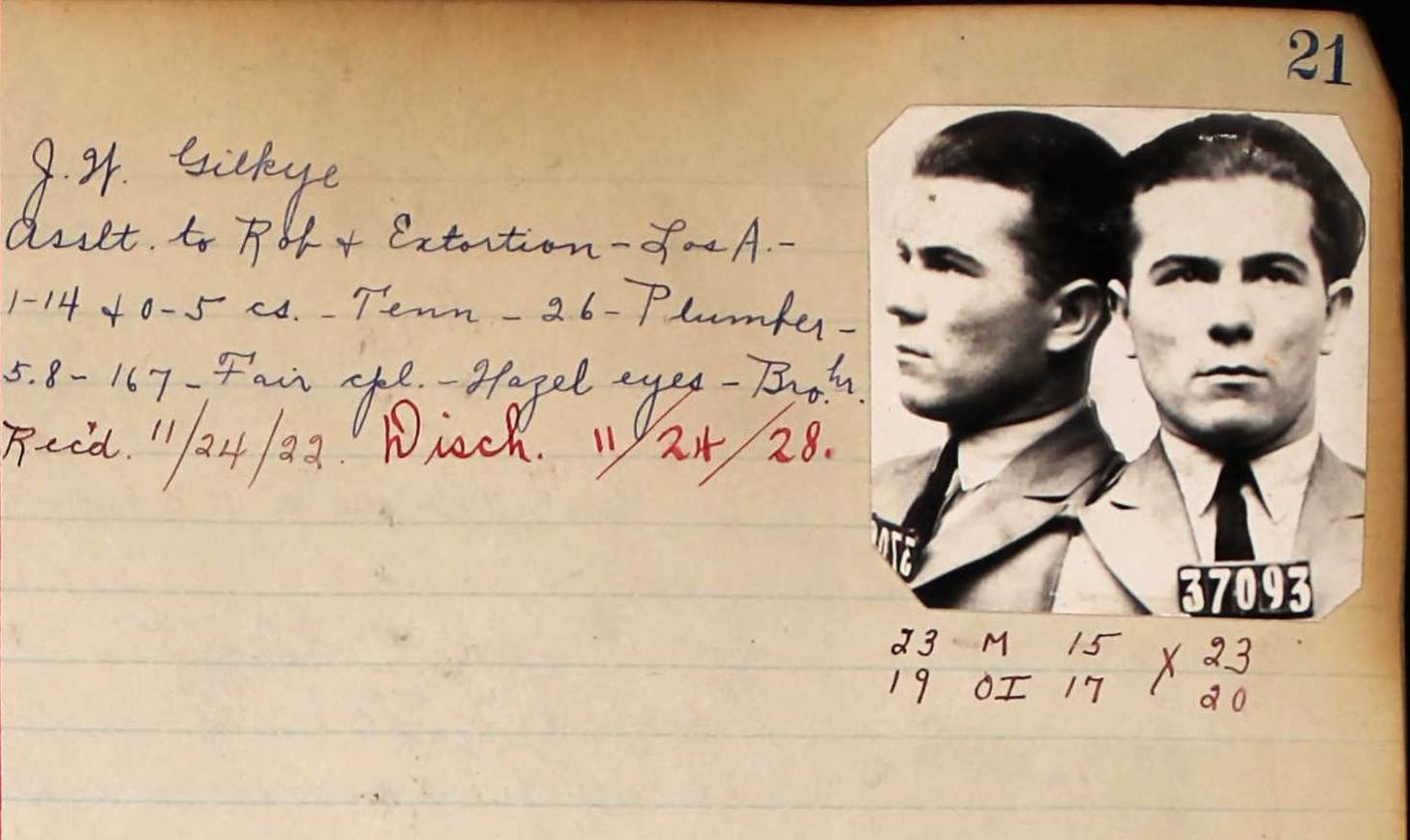

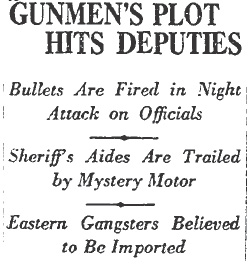

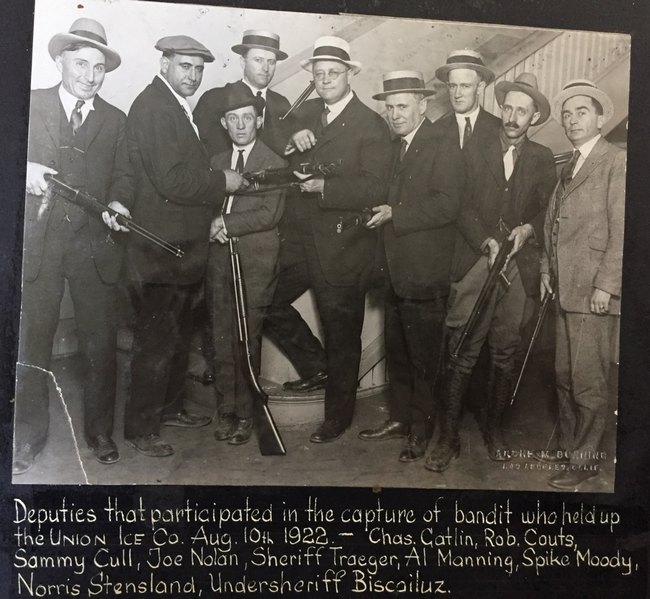

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence.

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence. Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.