Aimee Torriani’s self-proclaimed psychic abilities were underwhelming. She put forward the same theory that Earle’s brother-in-law had suggested — that the killer was a veteran of the world war. According to Aimee the mystery vet’s motive was simple, he respected Peggy Remington for her work with veterans and felt her husband was doing her dirt with his constant string of affairs.

Aimee Torriani’s self-proclaimed psychic abilities were underwhelming. She put forward the same theory that Earle’s brother-in-law had suggested — that the killer was a veteran of the world war. According to Aimee the mystery vet’s motive was simple, he respected Peggy Remington for her work with veterans and felt her husband was doing her dirt with his constant string of affairs.

Aimee also offered her opinion on the Remington’s relationship. “Peggy and Earle loved each other with a love which was so possessive that it was destructive.” Aimee went on to say, “I was surprised when Earle told me, more than two weeks ago when I met him downtown by chance, that an estrangement might occur. I have been away from Los Angeles a lot and have only seem him infrequently since I cam here to enter pictures almost three years ago.” Aimee had known Earle since she was a child, but she said, “I never knew Mrs. Remington well. She used to ask a number of my girl friends to assist her in giving benefit affairs for disabled war veterans, but I never was able to take part in any of the functions arranged by her.”

When she was asked about the parties Earle attended in the company of women other than his wife, Aimee said, “I have never been on any parties with Earle.” And she reiterated that Earle was “…never more than a big brother to me.”

The investigation into Earle’s murder became more complicated with every interview. Far from shining a psychic light on the slaying, Aimee had succeeded only in casting more doubt on the widow.

Chief of Police L.D. Oakes contacted Oakland authorities for information regarding the August 13, 1922 murder of “Deacon” Edward M. Shouse, a Bay Area bootleg king. Shouse may have been slain in retaliation for dropping a dime on a rival. Shouse had allegedly tipped off government officials to a landing at Monterey of a large cargo of illegal whiskey, and as a result someone was out a lot of money. Maybe the unknown someone was angry enough to kill. They tried, but Oakland PD and LAPD couldn’t make a connection between the deaths of the two bootleggers.

The strain of the her husband’s murder and subsequent investigation were so stressful that Peggy collapsed and was ordered to bed by her doctor.

Captain Home and Detective Sergeant Cline questioned Peggy in her sick bed and this time she was more forthcoming.

Peggy hoped that people would not judge Earle too harshly. She said, “He started (bootlegging) in a frantic effort to recuperate his fortunes. That was a long time ago. I begged him to quit. At first he said it was impossible. Recently, however, he promied he would get out of the terrible business. But—he didn’t.”

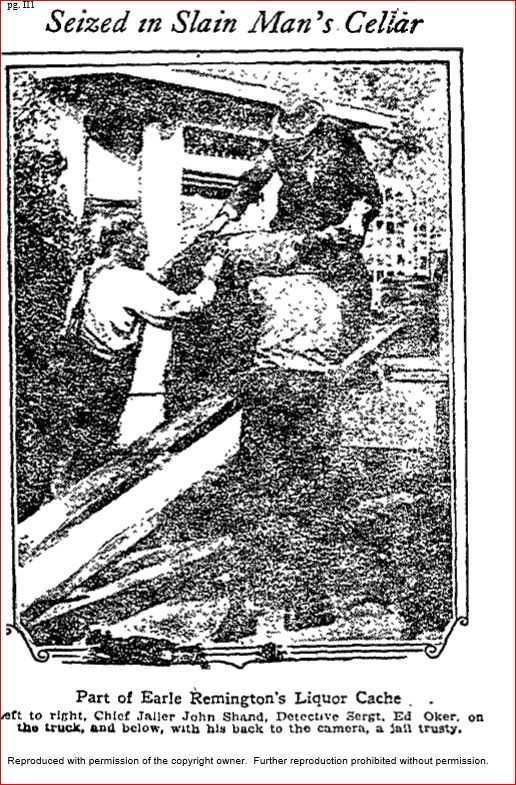

According to Peggy, Earle’s personality changed as he became more involved in bootlegging. And it wasn’t a change for the better. Peggy didn’t like his new friends. “And they were so different. In the mornings they would call at the front door, perhaps. Then a few would seek to gain admittance at the rear door of the house. Trucks would drive up to the house and unload the terrible stuff. An again a truck would be driven into the driveway to take whiskey away. i was compelled to give up entertaining. I couldn’t bear to bring my friends into the house. The odor of liquor was noticeable in every room. It was just one long nightmare.”

Most of the men who turned up at the Remington’s home were strangers to Peggy. She told investigators Home and Cline, “The telephone would ring. They would ask for Earle. A long conversation concerning ‘prices,’ ‘deliveries’ and ‘grades’ would follow. Sometimes Earle would get angry and following the calls say terrible things about the party with whom he had just conversed. I never made it any of my business to ascertain the identity of the party in question. All I wanted was his promise to quit the thing.”

Earle’s new friends did not bring out the best in him. Peggy said that Earle began drinking heavily. She said, “His business affairs were in a chaotic condition and this, combined with the dangers and worries involved in his activities as a bootlegger made him drink.” Earle also became obsessed with money. Peggy felt Earle lost sight of everything in his life but his desire for money.

On the day of his death, Peggy overheard Earle talking on the telephone. He was agitated and so angry that Peggy was convinced if the caller had been in the house there would have been a fist fight. Earle swore at the unknown caller and when he hung up he continued to rage for hours. If Earle had a falling out with a bootlegging partner or rival the situation could have escalated from verbal threats to murder.

Detectives pulled on multiple threads hoping to unravel the tangled case, but it was slow going. A search of Earle’s personal papers revealed the names of scores of people to whom he had sold liquor.

Dr. Wagner, the autopsy surgeon, threw the detectives another curve when he said that an X-ray showed that the second wound in Remington’s heart was not caused by a dagger but was caused by a freak discharge of the shotgun, or by some other weapon that had not been identified.

Detectives were frustrated and tired of running on the hamster wheel that the case had become; but quitting wasn’t an option so they kept digging.

Earle’s will caused police to take another hard look at Peggy. He hadn’t been destitute as had been thought — his estate was estimated to be in excess of $150K (equivalent to $2.1M in today’s dollars). That kind of money is one hell of an incentive to commit murder.

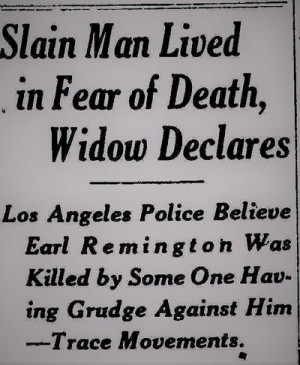

Peggy may have been a good suspect, but cops were still inclined to believe that Earle had died as a result of a dispute with another bootlegger. That theory gained credibility when, about a week after Earle’s murder, police learned that during the three months prior to his death he had been in fear of his life. Earle had reached out to some of his business associates telling them that he had gotten himself into a jam and might be killed. Unfortunately, Earle was tight-lipped about who wanted him dead.

The prognosis for a solution to Earle’s slaying improved when Earle’s sister paid a visit to the District Attorney to tell him that she was being watched and followed. Whoever was behind the mystery surveillance could be responsible for Earle’s murder.

Next time: The conclusion of the Society Bootlegger Murder.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair. Close on the heels of the first man’s visit to Cote’s home another young man, twenty year-old Alfred Dobriener of

Close on the heels of the first man’s visit to Cote’s home another young man, twenty year-old Alfred Dobriener of  Detective Lieutenant S.R. Lopez of the the LAPD said that Pearl had either gone to the end of the bus line and hiked up Franklin to take in the view alone, or she had ridden up in the car with the two men to the top of the hill. By virtue of its seclusion and spectacular views the spot was a local lover’s lane. But why would Pearl have gone there with two men?”

Detective Lieutenant S.R. Lopez of the the LAPD said that Pearl had either gone to the end of the bus line and hiked up Franklin to take in the view alone, or she had ridden up in the car with the two men to the top of the hill. By virtue of its seclusion and spectacular views the spot was a local lover’s lane. But why would Pearl have gone there with two men?”

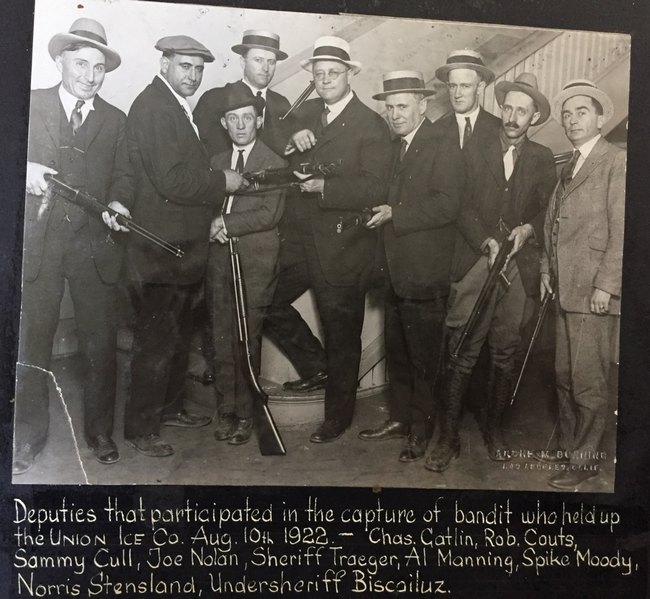

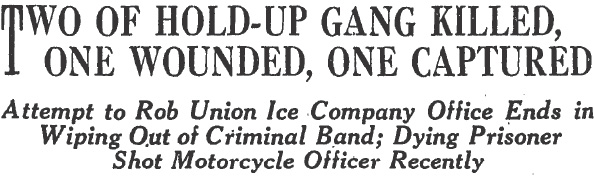

At 6 p.m. on August 10, 1922, deputies, armed with sawed-off shotguns, surrounded the ice company building. They stayed in the shadows waiting for the Burton gang to show up. It was a long wait. At 9:30 p.m. a car parked on the west side of Alameda. Several men exited the vehicle and climbed between the cars of a slow moving freight train. They approached the factory office.

At 6 p.m. on August 10, 1922, deputies, armed with sawed-off shotguns, surrounded the ice company building. They stayed in the shadows waiting for the Burton gang to show up. It was a long wait. At 9:30 p.m. a car parked on the west side of Alameda. Several men exited the vehicle and climbed between the cars of a slow moving freight train. They approached the factory office.

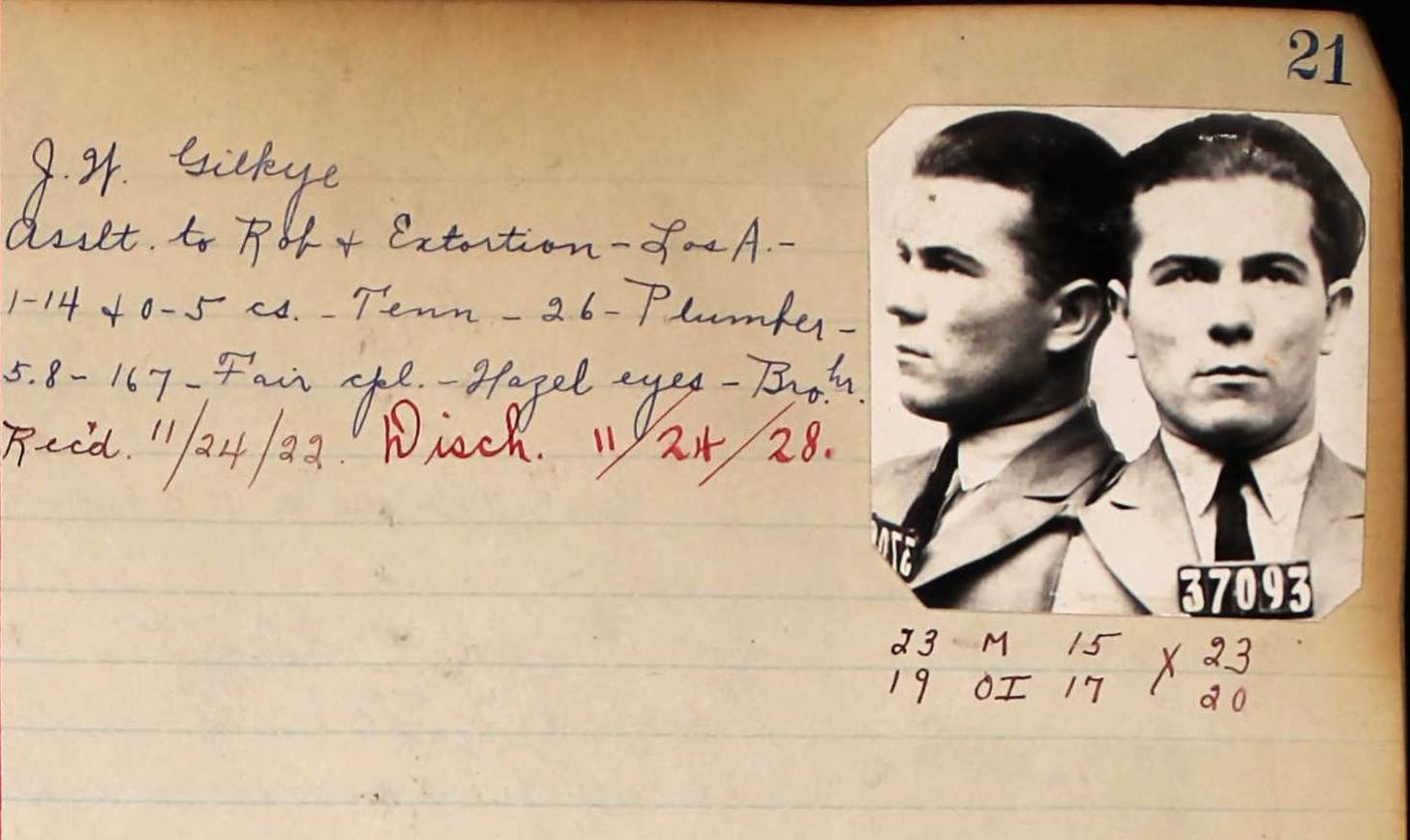

J.C. Gilkye, the surviving member of the gang, gave Chief Investigator Manning an earful about the activities of the group. Gilkye said that not all of the gang’s attempted crimes were successful. Far from it. But even with the failures, they had done pretty well in Los Angeles — until their final job. Had the Burton gang been completely wiped out as law enforcement hoped? If they could locate Burton’s sweetheart maybe they’d know for sure.

J.C. Gilkye, the surviving member of the gang, gave Chief Investigator Manning an earful about the activities of the group. Gilkye said that not all of the gang’s attempted crimes were successful. Far from it. But even with the failures, they had done pretty well in Los Angeles — until their final job. Had the Burton gang been completely wiped out as law enforcement hoped? If they could locate Burton’s sweetheart maybe they’d know for sure.

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence.

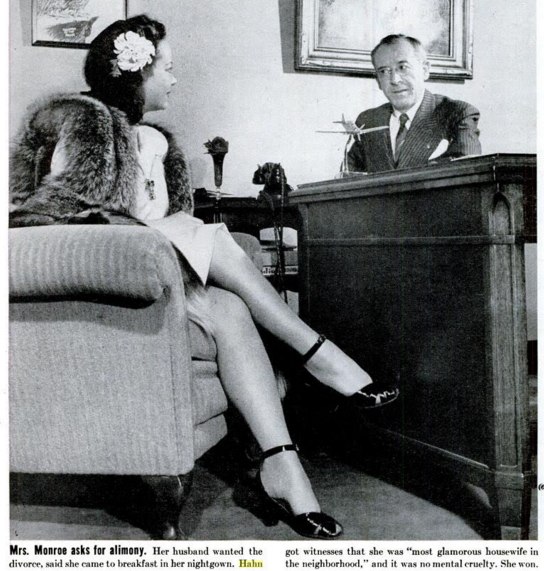

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence.![S.S. Hahn with a witness in Aimee Semple McPherson's trial. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/00021982_hahn_witness-in-McPherson-trial.jpg)

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario.

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario. With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

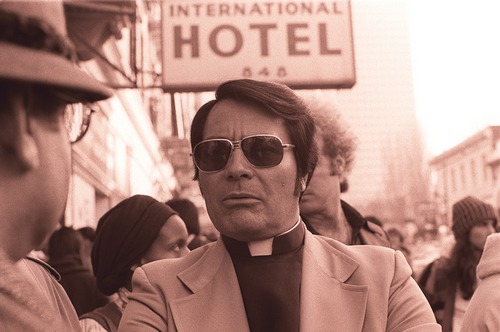

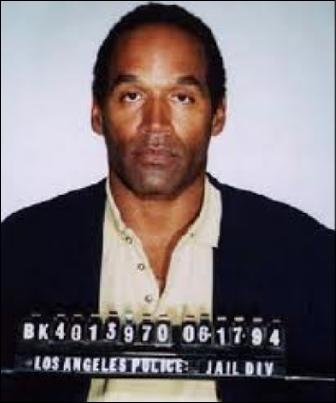

Here in L.A. there was the murder trial of O.J. Simpson, the so-called Trial of the Century. If you remove fame, wealth, and race and reduce the crime to its basic elements you end up with nothing more than a tragic domestic homicide–the type of crime which is altogether too common everywhere–yet the case continues to fascinate.

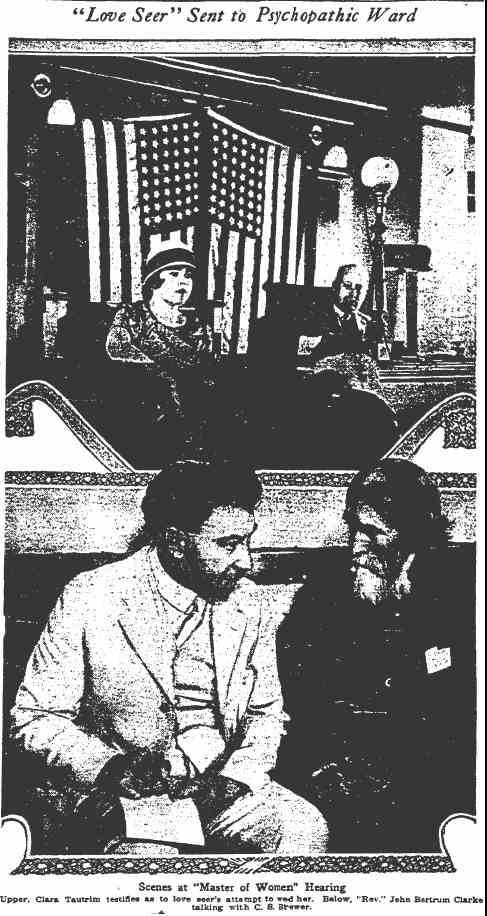

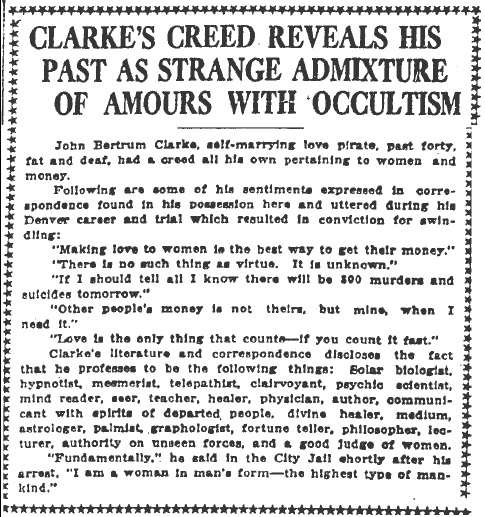

Here in L.A. there was the murder trial of O.J. Simpson, the so-called Trial of the Century. If you remove fame, wealth, and race and reduce the crime to its basic elements you end up with nothing more than a tragic domestic homicide–the type of crime which is altogether too common everywhere–yet the case continues to fascinate. him in all sorts of schemes, most of which smacked of extortion. The cops thought that the scams were primarily small ones, until they uncovered evidence that John was attempting to merge several cults into a “spiritualist trust”. Among the plans he had for the trust were: Mexican distilleries, deals in bat guano, and investments in copper mines and oil stocks. He planned to operate the trust out of a home offered for sale by Mrs. Dorothy Parry. John represented himself to Dorothy as the agent for a purchaser who could afford the asking price of $70,000 (equivalent to nearly $10M in 2016 dollars). But rather than putting Dorothy together with a buyer, John bombarded her with letters and poems. Dorothy told investigators: “The man’s persistence was so annoying that I had to move and asked my hotel not to give my forwarding address. But somehow Clarke managed to obtain it and followed me to this address. As the result of his visits I have been afraid to answer the door bell or go to the telephone.”

him in all sorts of schemes, most of which smacked of extortion. The cops thought that the scams were primarily small ones, until they uncovered evidence that John was attempting to merge several cults into a “spiritualist trust”. Among the plans he had for the trust were: Mexican distilleries, deals in bat guano, and investments in copper mines and oil stocks. He planned to operate the trust out of a home offered for sale by Mrs. Dorothy Parry. John represented himself to Dorothy as the agent for a purchaser who could afford the asking price of $70,000 (equivalent to nearly $10M in 2016 dollars). But rather than putting Dorothy together with a buyer, John bombarded her with letters and poems. Dorothy told investigators: “The man’s persistence was so annoying that I had to move and asked my hotel not to give my forwarding address. But somehow Clarke managed to obtain it and followed me to this address. As the result of his visits I have been afraid to answer the door bell or go to the telephone.” Soul contracts and shady real estate deals were bad enough, but what about the possibility that John had been involved in the suspicious deaths of two women with whom he had been involved?

Soul contracts and shady real estate deals were bad enough, but what about the possibility that John had been involved in the suspicious deaths of two women with whom he had been involved?

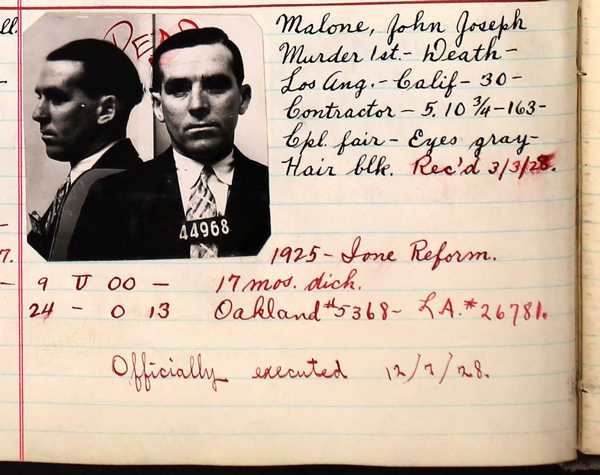

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace. On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman. John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

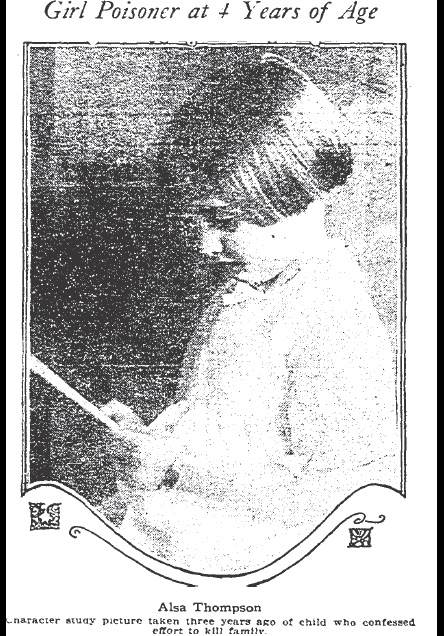

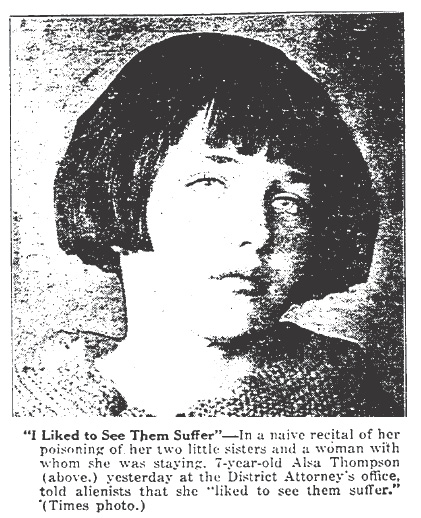

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell. Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.” Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”