A Celebration

On June 2, 2022, I attended the banquet to celebrate the centenary of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide Bureau.

Founded in 1921, the Bureau’s celebration should have taken place last year but, like so many things, they put it on hold. It was worth the wait.

Nearly 500 people gathered at Pacific Palms Resort in the City of Industry to honor past and present detectives. I am honored to know a few of them personally.

During the 6+ years, I have volunteered with LASD’s museum, I’ve met, and worked with, a few of the department’s retired homicide investigators. Most notably, Frank Salerno and Gil Carrillo. You know them from the Night Stalker case in the mid-1980s.

They are among the most famous of the Bulldogs, but each of the investigators I’ve met is truly outstanding. I’ve learned that being a homicide investigator is a calling. It’s not a j-o-b. It takes intelligence, skill, and heart to deal with the cases that cross their desks daily.

Bulldog Attitude

A person I admire and respect is Ray Lugo. Ray has been a homicide detective for over 20 years.

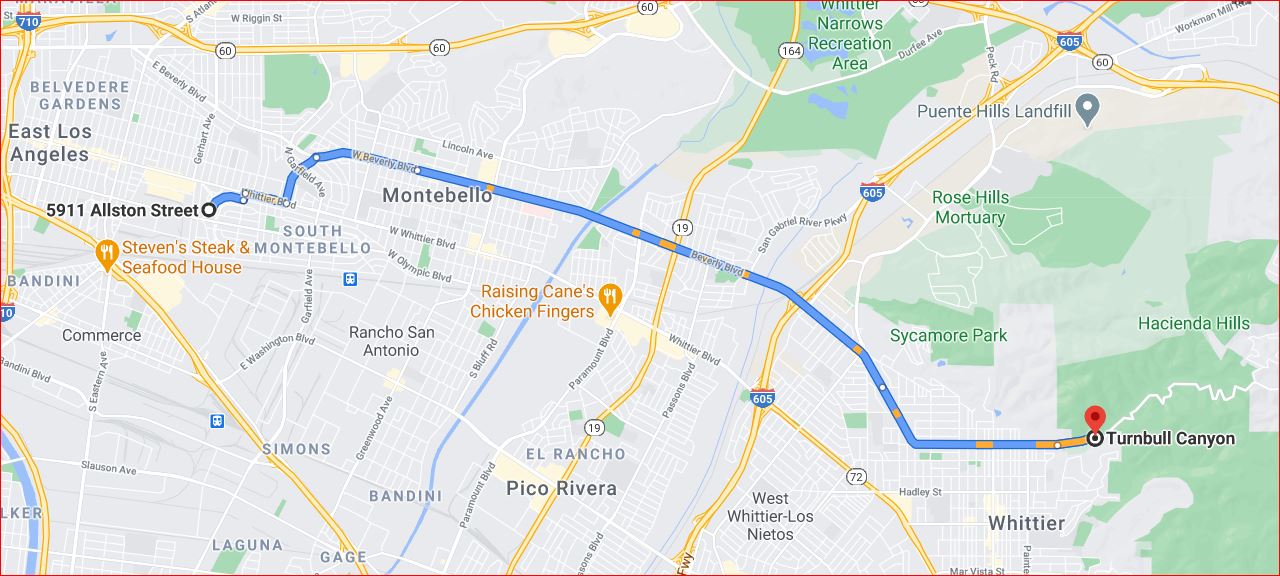

An example of Ray’s bulldog attitude is the investigation into the 2006 murder of Iraq war veteran, 24-year-old Jesse Aguilar, found shot to death inside the trunk of his car, which was found on fire on Oct. 26, 2006, in the Los Angeles Riverbed near Paramount Boulevard in South Gate.

It took a decade to solve the case, and over twelve years before the killers went to trial. and to prison.

Jesse’s mother, Nancy, said,

“It’s been a relief that there’s going to be accountability. I want to look into the killers’ eyes. I want to see them.”

She said this about Ray Lugo,

“God sent Ray (Lugo) for this case because he never quits.”

It does not matter if they are working a case that is hours old, or decades old, they have the same determination to find a solution.

Bow WOW–A Brief History of the Bulldogs

How did the Sheriff’s Homicide Bureau earn their nickname?

In a December 18, 1977 Los Angeles Times article by Myrna Oliver and Bill Farr.

Under the headline “Sheriff’s ‘Bulldogs’ Hang in Where LAPD Doesn’t,” a veteran prosecutor is quoted, “You want to know why the Sheriff’s conviction rate is so much higher in homicide, not just last year, but for several years? It is because the guys from the Sheriff’s Homicide Bureau are a bunch of bulldogs. From the time they are called to the murder scene, until we prosecutors get the case through the courts, they never let go and I mean on every murder case, not just the high publicity cases. They are routinely tenacious, and the investigator assigned to the case sticks with it until the end. There is no shuttling cases to somebody else like at LAPD. With the Sheriff’s people, if you need follow-up done, they are marvelous; they are super. They even give you their home phone number in volunteering to help out.”

In the same article, a defense attorney had this to say, “I can tell you that almost every defense attorney I’ve ever talked to would rather try a murder case LAPD than against the Sheriff’s people. The Sheriffs are just tougher.”

L.A.’s First Serial Killer & The Birth of the Bureau

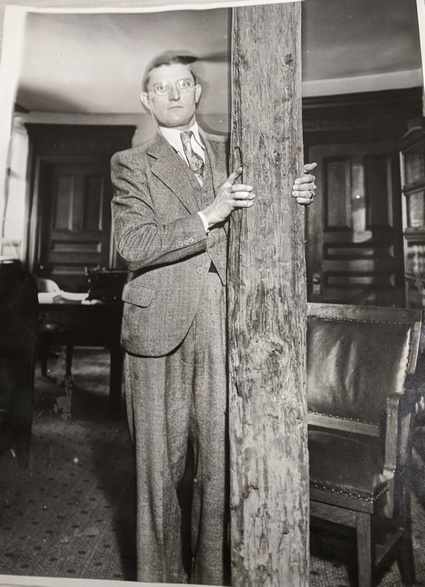

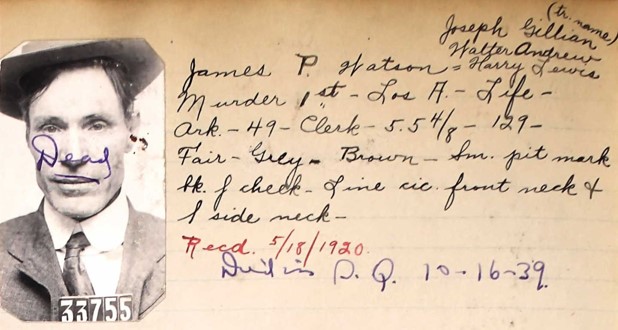

It is interesting to note that the birth of the bureau directly results from the city’s first bona fide serial killer, James Bluebeard Watson.

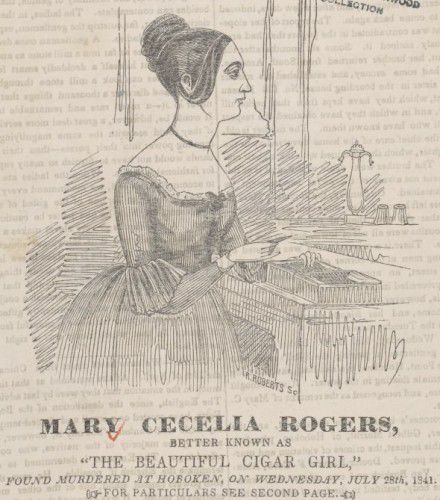

Kathryn Wombacher, an unmarried seamstress, took a chance on love when she answered an ad in a local Spokane, Washington newspaper in 1919. The ad’s author, Walter Andrew, described himself as a man in his 30s—sensitive and caring, with good habits, a decent income, and a desire to marry. Kathryn immediately answered the ad. Their meeting went well and they married in November 1919.

It thrilled Kathryn to move with her new husband to Hollywood. There was a constellation of stars living in the area. She wondered if she would meet Charlie Chaplin or Mary Pickford.

Even more exciting than moving to Hollywood was the knowledge that she married a government secret agent. Walter’s work lost some of its luster for Kathryn when his absences from home became longer and more frequent. She suspected her new husband of infidelity.

She hired a private detective and together they uncovered Walter’s secret. His real name was James Watson. He was a bigamist, and a multiple murderer with no connection to the secret service. He killed at least 25 of his wives across the western U.S. and Canada.

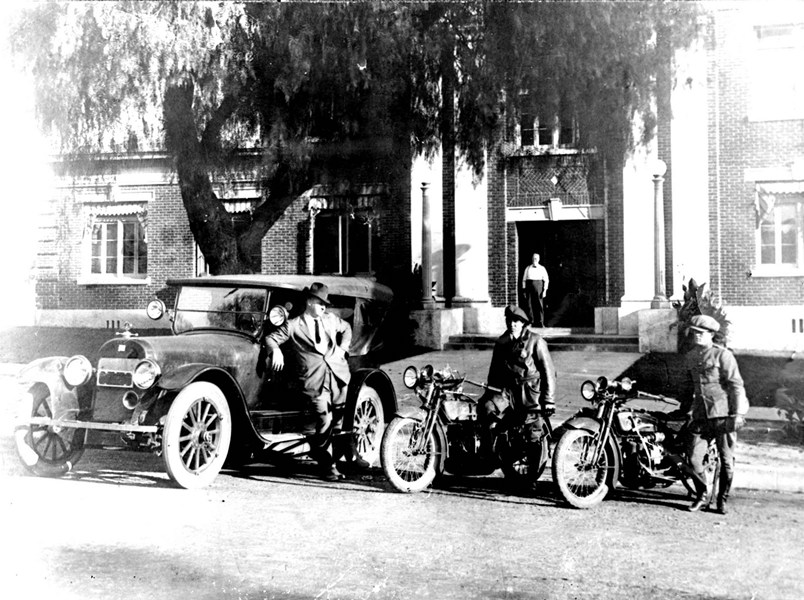

There was no homicide bureau then. Sheriff Traeger investigated on his own. It was not a one-person job. At the successful end of the investigation, in 1921, Chief of the Criminal Division, Harry Wright, insisted that Sheriff Traeger create the Homicide Detail. That was the first step toward the modern bureau.

Going Forward

In the decades since the Bluebeard Watson case, Sheriff’s homicide bureau has tackled some of the most difficult, and bizarre, murders in the county’s history; and they continue to do amazing work.

Advancements in science have provided detectives with valuable tools, but no matter what the science, it will always take a detective’s insight and skill to put together a case.

Speaking with Mike Fratantoni, the Sheriff’s museum curator, we agreed that each generation of homicide detectives passes the torch to those who follow. It is a tradition of which the department is justifiably proud.

Thanks for all you do, Bulldogs!