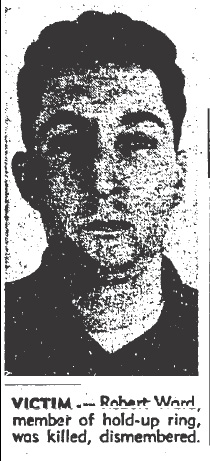

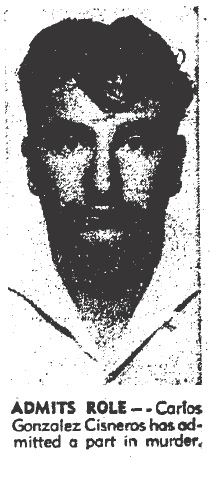

After shooting Bob Ward to death with a .38, Allen Ditson had to figure out what to do with the body. At least Carlos Cisneros was there to help him. Carlos began to dig a grave with his bare hands until Allen brought him a butcher knife from the car. Once the grave was ready Allen said that they would have to dismember Bob to prevent identification if someone should discover his remains. Using the butcher knife they removed Bob’s head and each arm at the elbow. They buried the remains and then tossed the head and arms into the truck of the car and drove back Allen’s store.

After shooting Bob Ward to death with a .38, Allen Ditson had to figure out what to do with the body. At least Carlos Cisneros was there to help him. Carlos began to dig a grave with his bare hands until Allen brought him a butcher knife from the car. Once the grave was ready Allen said that they would have to dismember Bob to prevent identification if someone should discover his remains. Using the butcher knife they removed Bob’s head and each arm at the elbow. They buried the remains and then tossed the head and arms into the truck of the car and drove back Allen’s store.

While Allen and Carlos were coping with the dead body, Keith Slaten turned up at the house of his friend Martha Hughes. He told her that he’d been in a fight and wanted to clean up his car. He was covered with blood and shaking like a leaf and Martha told him she didn’t believe he’d been in a fight. He blurted out: “Well, God damn. All right, so we killed him.” Allen couldn’t keep his mouth shut either. The day after Bob’s murder he told Eugene Bridgeford everything that had happened after he pleaded illness and left.

What happened to Bob’s head and arms? Allen and Carlos took them to the home of Christine Longbrake a few days after the murder. Christine was an acquaintance of Allen’s and a couple of weeks before the crime she’d been in Allen’s shop and he’d told her that “there was someone they had to get rid of” because the man was trying to blackmail him. Allen asked to use her garage as a place to get rid of the guy but she thought he was kidding. When Allen and Carlos turned up with two boxes Christine knew she couldn’t refuse any request they made. She stayed upstairs while the boxes were taken to the cellar. Allen knocked Bob’s teeth out with a hammer then placed what was left of him in the hole and then poured in a bottle of acid. When the men came back upstairs Christine smiled nervously and said: “Is it somebody I know?” They smiled back and Allen said that she wouldn’t know him. Then he and Carlos drove out to Hansen Dam and tossed Bob’s teeth and dental plate into a gravel pit.

Christine hadn’t seen the last of Allen and Carlos. Not more than a few days after they’d buried the boxes in her cellar Carlos stopped by and told her everything. He even told her what was in the boxes underneath her house. Her nerves weren’t soothed when he told her that he could never kill a woman. In fact she was so unnerved that she told Allen she was going to move “…because I couldn’t stand living in this house …” Allen told her that if it bothered her so much he’d pay her rent if she’d just hang on a bit longer.

A bit longer turned out to be several months. In June 1960 Allen asked George Longbrake, Christine’s brother-in-law, if he would dig up the two arms and head under the house. George agreed and Allen bought him some aluminum foil so he could wrap up the bits of Bob that remained. Then, since it seemed the entire Longbrake family was involved anyway, Allen asked Wynston Longbrake, Christine’s husband, if he’d “help bury something.” Allen, Carlos, and Wynston drove from L.A. on Highway 99 to a place about 14 miles from Castaic Junction. He turned off the highway for about 100 yards. Carlos waited in the car while the other two carried the macabre foil wrapped packages out of sight, then dug a post-hole and buried them.

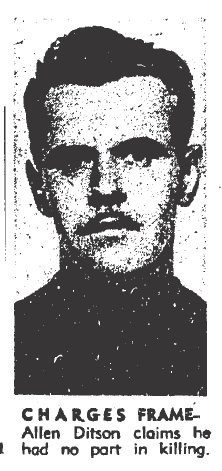

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.

Allen maintained his innocence, but Carlos appeared to be genuinely remorseful and he wanted to talk. In his 1959 book, The Compulsion to Confess, Theodore Reik said “There is … an impulse growing more and more intense suddenly to cry out his secret in the street before all people, or in milder cases, to confide it at least to one person, to free himself from the terrible burden. The work of confession is thus that emotional process in which the social and psychological significance of the crime becomes preconscious and in which all powers that resist the compulsion to confess are conquered.”

Allen’s protestations of innocence didn’t sway the jury of five men and seven women. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. Carlos was also found guilty in Bob’s murder and sentenced to death. In early November 1962, with their executions imminent, Governor Brown presided over a clemency hearing. Carlos’ remorse saved him. His sentence was commuted to life.

Allen never admitted his guilt to the police, but he did confess to nearly everyone else he knew. On November 21, 1962, without requesting a special holiday meal, Allen kept his Thanksgiving Eve date with the gas chamber.

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

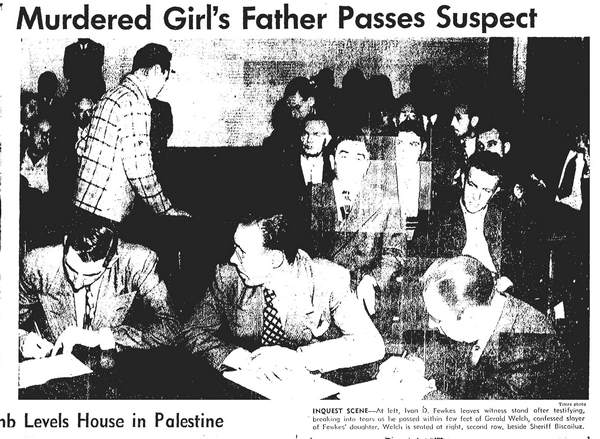

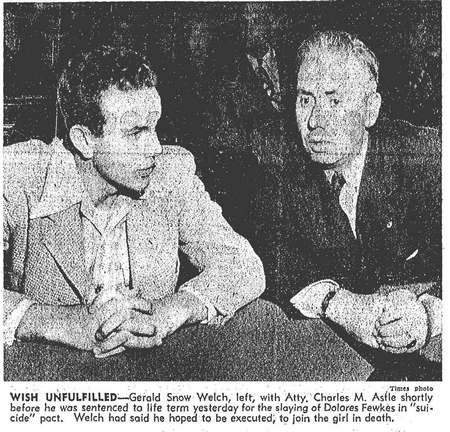

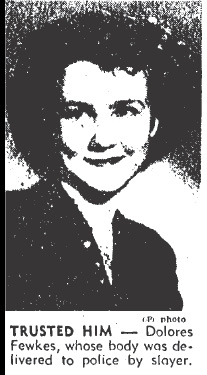

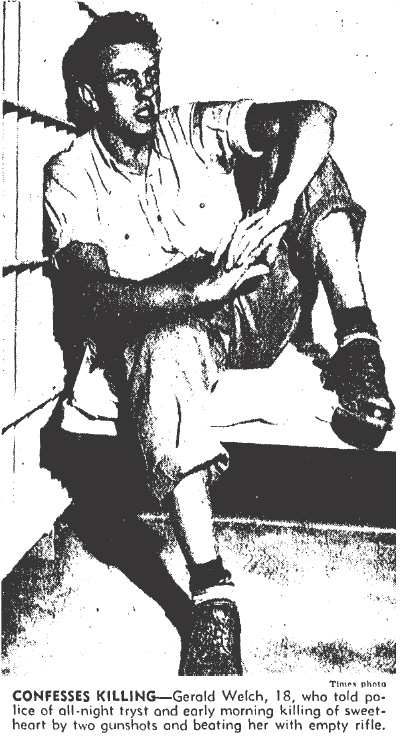

Gerald Welch confessed to killing Dolores Fewkes claiming that it was a suicide pact gone wrong. Sheriff’s investigators, Detective Sergeant Charles Gregory and his partner, L.E. Case, took him out to the lonely picnic ground where the crime had occurred for a reenactment. The place was peaceful, tucked away in a grove of tall pine treees. The picnic bench where Dolores had been shot was stained with her blood and so was the sandy soil beneath it.

Gerald Welch confessed to killing Dolores Fewkes claiming that it was a suicide pact gone wrong. Sheriff’s investigators, Detective Sergeant Charles Gregory and his partner, L.E. Case, took him out to the lonely picnic ground where the crime had occurred for a reenactment. The place was peaceful, tucked away in a grove of tall pine treees. The picnic bench where Dolores had been shot was stained with her blood and so was the sandy soil beneath it.

A few days following her death the 16-year-old was placed in an open casket surrounded by several large floral wreaths. Her funeral was held in North Long Beach and she was laid to rest in Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier. At least Gerald’s request to a judge to be allowed to attend her funeral had been denied. Her parents and surviving siblings were suffering enough without having to share one of the worst days of their lives with Dolores’ killer.

A few days following her death the 16-year-old was placed in an open casket surrounded by several large floral wreaths. Her funeral was held in North Long Beach and she was laid to rest in Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier. At least Gerald’s request to a judge to be allowed to attend her funeral had been denied. Her parents and surviving siblings were suffering enough without having to share one of the worst days of their lives with Dolores’ killer. The all-day hearing in Judge Fricke’s court began with Gerald pleading guilty to murdering Dolores. The judge read letters written by Dolores to Gerald. One of them was a poignant reminder of Dolores’ youth. Her declaration of love was surrounded by biology class doodles and it read: “I told you once that I could never love another guy and I still mean it. What good is loving a guy when he doesn’t love you enough to care whether he hurts you or not?” Like most high school girls in 1947 she dreamed of marriage. Among her notebook scribbles she had practiced signatures “Mrs. Jerry Welch,” Mrs. Dolores Welch” and “Mrs. G.S. Welch.” Fraught with the expected teenage angst, another of Dolores’ letters to Gerald read: “I’ll tell you what I expected of you. I wanted you to see me as much as possible, to think about me as much as I do you–to not want to go anywhere without you, but it was impossible. These few things would have kept me happy, happy just to know that you don’t enjoy doing things without me. I guess it didn’t work out. I don’t know what you are going to do, but as for me, I’ll probably go on living in a rut, going to school, then to college. I’ll never ever be seen with another one unless it is you. Unless you think you want me bad enough to make me happy, I’ll wait for you forever if I have to. Yours forever, Dolores”

The all-day hearing in Judge Fricke’s court began with Gerald pleading guilty to murdering Dolores. The judge read letters written by Dolores to Gerald. One of them was a poignant reminder of Dolores’ youth. Her declaration of love was surrounded by biology class doodles and it read: “I told you once that I could never love another guy and I still mean it. What good is loving a guy when he doesn’t love you enough to care whether he hurts you or not?” Like most high school girls in 1947 she dreamed of marriage. Among her notebook scribbles she had practiced signatures “Mrs. Jerry Welch,” Mrs. Dolores Welch” and “Mrs. G.S. Welch.” Fraught with the expected teenage angst, another of Dolores’ letters to Gerald read: “I’ll tell you what I expected of you. I wanted you to see me as much as possible, to think about me as much as I do you–to not want to go anywhere without you, but it was impossible. These few things would have kept me happy, happy just to know that you don’t enjoy doing things without me. I guess it didn’t work out. I don’t know what you are going to do, but as for me, I’ll probably go on living in a rut, going to school, then to college. I’ll never ever be seen with another one unless it is you. Unless you think you want me bad enough to make me happy, I’ll wait for you forever if I have to. Yours forever, Dolores”

He admitted that when he originally contemplated suicide he had no intention of taking Dolores with him but: “She said she couldn’t stand to be left behind and we decided to go together.”

He admitted that when he originally contemplated suicide he had no intention of taking Dolores with him but: “She said she couldn’t stand to be left behind and we decided to go together.”

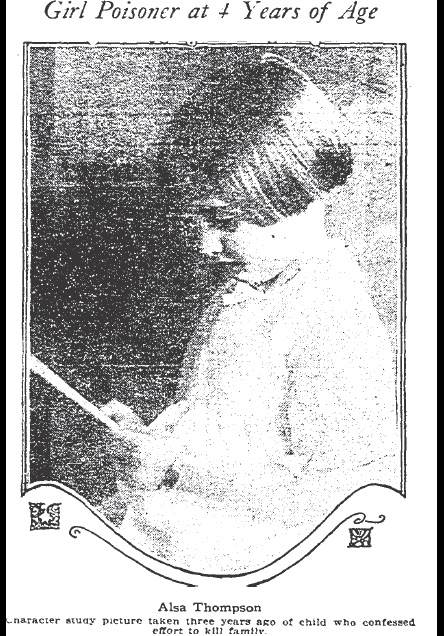

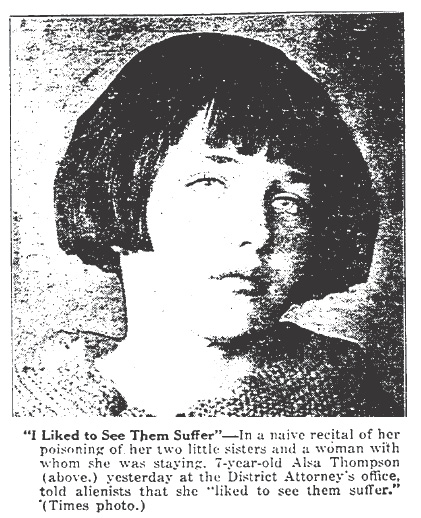

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.” Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.” On February 3, 1925 a bizarre story broke in the local news — it was alleged that seven year old Alsa Thompson had attempted to murder a family of four with a mixture of sulphuric acid and ant paste she had added to the evening meal. The intended victims tasted the food, but it was so awful they pushed their plates away.

On February 3, 1925 a bizarre story broke in the local news — it was alleged that seven year old Alsa Thompson had attempted to murder a family of four with a mixture of sulphuric acid and ant paste she had added to the evening meal. The intended victims tasted the food, but it was so awful they pushed their plates away. Alsa was taken by Policewoman Elizabeth Feeley to the Receiving Hospital where she was questioned by police and surgeons about the poisoning plot. The little girl cheerfully confessed that she had indeed attempted a quadruple homicide and that she’d done it because: “…I am so mean.”

Alsa was taken by Policewoman Elizabeth Feeley to the Receiving Hospital where she was questioned by police and surgeons about the poisoning plot. The little girl cheerfully confessed that she had indeed attempted a quadruple homicide and that she’d done it because: “…I am so mean.”

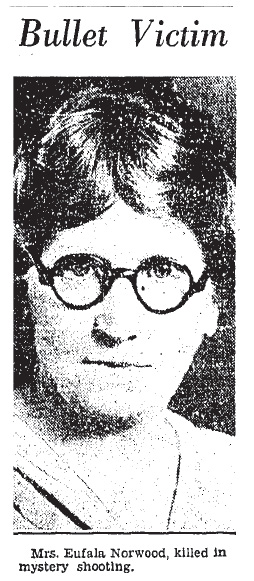

The fight between Isa Lang and Edith Eufala Norwood over an avocado sandwich ended in death. Isa had grabbed a gun from her former landlady’s closet and shot her in the back of the head. Eufala died instantly.

The fight between Isa Lang and Edith Eufala Norwood over an avocado sandwich ended in death. Isa had grabbed a gun from her former landlady’s closet and shot her in the back of the head. Eufala died instantly.

Astonishingly, Isa was able to convince the Department of Correction that by giving up her parole and returning to prison she would be treated more humanely than she had been in the nursing home on the outside. Actually, now that I think about some of the stories I’ve read about nursing homes, maybe her request wasn’t so shocking after all.

Astonishingly, Isa was able to convince the Department of Correction that by giving up her parole and returning to prison she would be treated more humanely than she had been in the nursing home on the outside. Actually, now that I think about some of the stories I’ve read about nursing homes, maybe her request wasn’t so shocking after all.

The next day William Norwood, who worked as the registrar as the White Memorial Hospital down the street from his mother’s house, dropped by to see her. When he entered the house he noticed it was extremely quiet. He called out but there was no answer. He went into the kitchen and that where he found his mother. She was dead, but there was nothing to suggest foul play until she was examined at the morgue.

The next day William Norwood, who worked as the registrar as the White Memorial Hospital down the street from his mother’s house, dropped by to see her. When he entered the house he noticed it was extremely quiet. He called out but there was no answer. He went into the kitchen and that where he found his mother. She was dead, but there was nothing to suggest foul play until she was examined at the morgue.

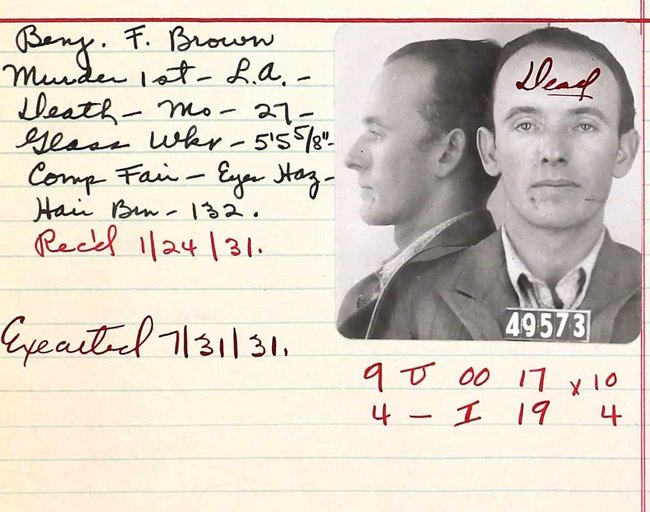

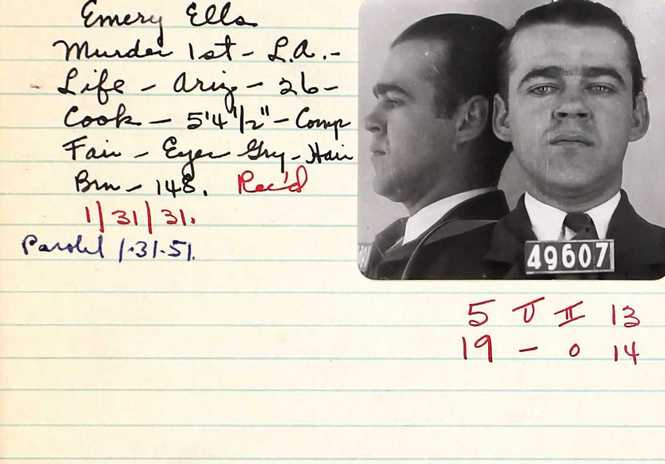

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity.

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity. Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.